Meat industry updating labeling system

Don’t know your pork butts from your rump roasts? It may be getting a little easier.

The American meat industry is rolling out a refresh of the often confusing 40-year-old system used for naming the various cuts of beef, pork, lamb and veal. That’s because the system – the Uniform Retail Meat Identification Standards, or URMIS – was designed more for the needs of retailers and butchers than for the convenience of harried shoppers more familiar with Shake ’n Bake than boneless shank cuts.

The bottom line is that meat counter confusion isn’t good for sales. So after nearly two years of consumer research, the National Pork Board, the Beef Checkoff Program and federal agriculture officials have signed off on an updated labeling system that should hit stores just in time for prime grilling season.

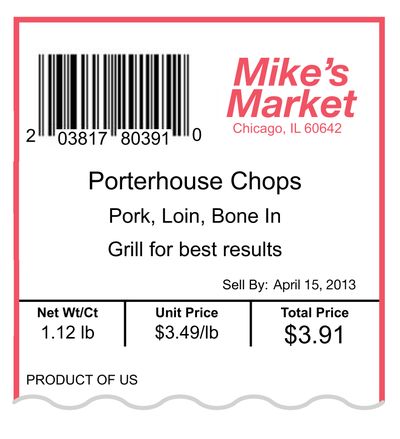

In all, more than 350 cuts of pork and beef (veal and lamb updates are coming later) will sport the new labels, which will include not only simplified names, but also detailed characteristics of the meat and cooking guidelines. So what once was called pork butt – and actually does not come from the pig’s nether region – will now be called a Boston roast and be described as a bone-in pork shoulder.

“The problem is consumers didn’t really understand the names that were being used, and still don’t,” said Patrick Fleming, director of retail marketing for the Pork Board. “The names confused consumers to the point where they’d go, ‘You know, the information doesn’t help me know how to use it, so I’m going to stop using it.’ That was a wake-up call for both the beef industry and pork industry.”

Where appropriate, the new labels also will use universal terms across species – a bone-in loin cut will be called a T-bone whether it’s pork or beef – as well as reduce label clutter. Before the update, a properly labeled sirloin steak would be called a “beef loin top sirloin steak, boneless.” Now it will be called … a sirloin steak.

Meat labels are federally regulated. And though the URMIS system is a voluntary one, nearly 85 percent of food retailers use it. Those who don’t must use either alternative federally approved labels, or submit their own for approval. The backbone of URMIS, which was launched in 1973, is butchering and anatomical terminology. Even at launch, consumer understanding of that was weak.

“That old system just wasn’t really doing its job to communicate to the consumer,” said Trevor Amen, director of market intelligence for the Beef Checkoff Program. “If you’re a butcher or a meat cutter, you really know what part of the animal it comes from. But if you’re a consumer, you just want to know what it is and what to do with it.”

Though the new names may catch on, already-published cookbooks and recipes could call for meats by different names. Will people know to buy a New York chop if a pork recipe calls for a top loin chop? And what about older cooks who grew up with legacy names, such as pork rump (now called leg sirloin)?

“The intent certainly was not to confuse consumers, but there are some situations where that certainly could happen,” said Bucky Gwartney, a federal agriculture marketing specialist who worked with the meat industry to formulate the changes. “We tried to make sure even though some of these changes were fairly dramatic, they were still grounded in the original cut (of meat).”