New MAC exhibit devoted to man with a towering résumé

• A preserved California condor, 9 feet in wingspan.

• A preserved albatross, also 9 feet in wingspan.

• A replica wall of the Spokane House, the trading post where Douglas stayed in 1826.

• A replica wall of the cedar bark lodge where Douglas lived at Fort Vancouver.

And no doubt the MAC would have brought in something even bigger – a mature Douglas fir – if only one of those 200-foot behemoths would have fit inside the hall.

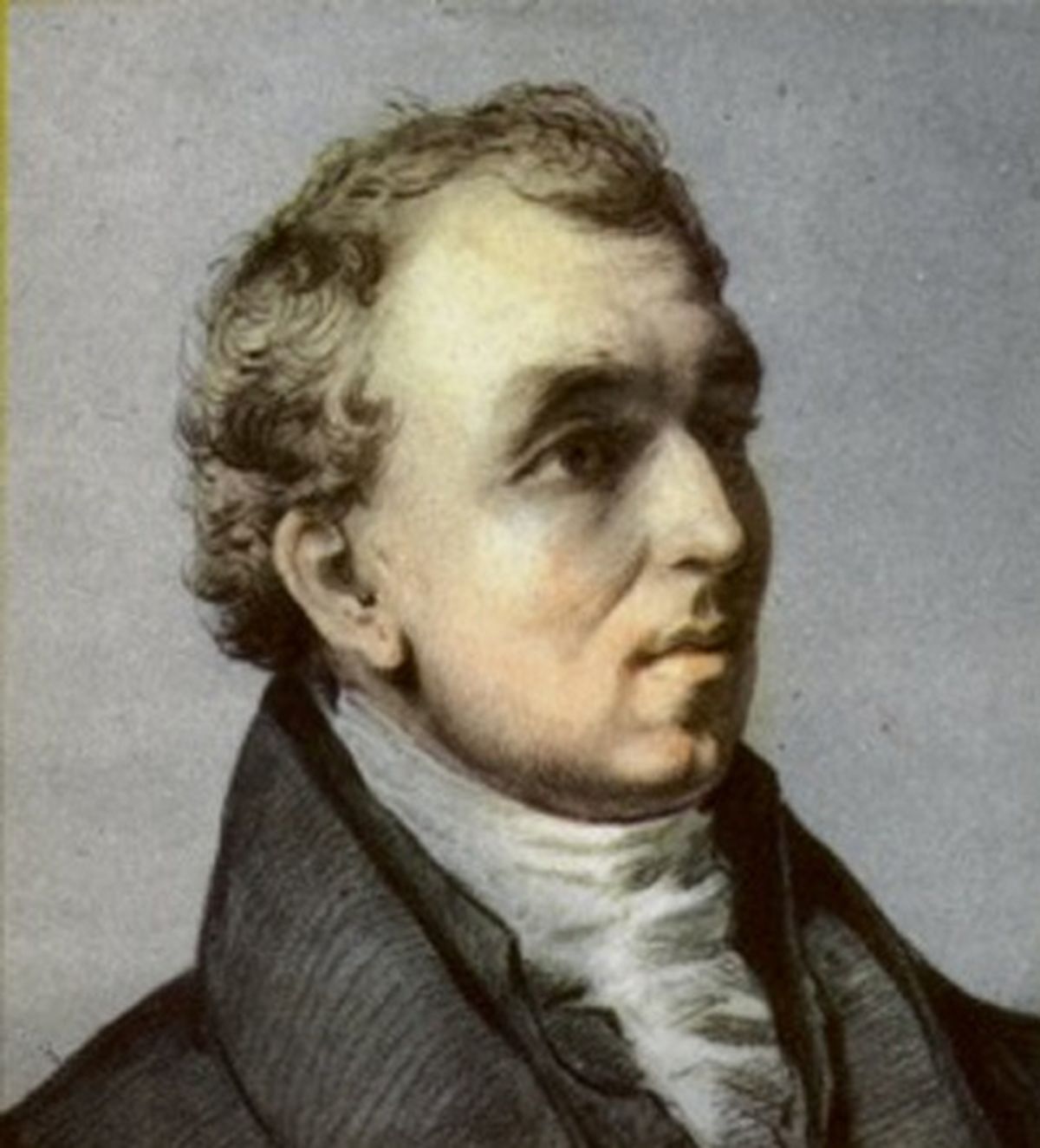

The Douglas fir is the single most towering reason why Scottish naturalist David Douglas is known today. Yet with this exhibit, visitors will discover hundreds and hundreds of other reasons why Douglas is worth knowing.

In two trips to the Northwest between 1824 and 1833, Douglas collected more than 200 species of plants, birds and animals that were new to Western science. Some of these still seem exotic to us now – we haven’t seen a condor on the Columbia in a long time – but others, such as salal and Douglas maple, are familiar to all who roam the forests and trails of today’s Northwest.

In the MAC exhibit, you can see some of the original plant specimens that Douglas collected, preserved, and then “shipped back to London, where they have been studied by botanists for almost 200 years,” said co-curator Jack Nisbet, a Spokane writer and naturalist and the author of “The Collector: David Douglas and the Natural History of the Northwest.”

About 11 of these brown and brittle specimens were loaned to the MAC from their home at the Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew, outside of London. Visitors can examine them through magnifying glasses and see original pages from Douglas’ own notebooks. For example, you’ll see a specimen of one of our region’s showiest wildflowers, the Sagebrush Mariposa Lily, with Douglas’ comment: “One of the most lovely of plants; flowers large purple.”

Douglas has long been a big name in the natural history of the West, but this exhibit shows why he was an especially influential figure right here in the Inland Northwest. Much of Douglas’ field research was conducted on the upper Columbia Plateau. Douglas explored the Spokane River, Kettle Falls and dozens of other spots from Walla Walla to British Columbia.

“I find this Country to be so exceedingly interesting that I have resolved to devote the whole of this Season to the Upper Country,” wrote Douglas. “… This part of the Columbia is by far the most beautiful and varied I have yet seen.”

Marsha Rooney, the MAC’s curator of history, co-curated the exhibit with Jack and Claire Nisbet, a husband-wife writing and research team. The Nisbets have devoted years to studying the impact that Douglas had on this region’s natural history.

Why take the time to get to know Douglas?

“Douglas was the first trained naturalist to visit a huge swath of the Inland Northwest,” Nisbet said. “In addition to identifying and naming dozens of familiar plants, birds and animals, his writings offer insights into the human landscape during a crucial period of transition in our region’s history.”

This landscape, long shaped by native cultures, was just beginning to be shaped by European influences.

Douglas’ research and writings give us an invaluable look at what our land was like before newcomers settled it.

The exhibit devotes considerable space to the flora and fauna of the Inland Northwest. You’ll see a drawing and description of a fish weir, in which tribal people speared more than 1,000 Chinook salmon in one day on the Spokane River.

In one part of the exhibit, visitors can crawl into a tent similar to the one Douglas used on his travels through our sagelands and forests. The exhibit also goes farther afield to tell the story of Douglas’ brief life, from his birth in Scotland in 1799 to his death in 1834 on the slopes of Hawaii’s Mauna Kea. The exhibit includes a recreation of the London workroom where he worked on his specimens between journeys.

In fact, the exhibit has so much regional interest that the MAC is only the first stop on this exhibit’s journey. After the exhibit closes at the MAC in August 2013, it will be packed up and moved to the Washington State History Museum in Tacoma, where it will be on display from September 2013 to February 2014.

“It’s a first for us, to create an exhibit here and then travel it to the state museum,” Rooney said.

Meanwhile, if you are inspired by this exhibit, it shouldn’t be too difficult to step out the museum doors and find another monument to David Douglas. Towering Douglas firs are easy to find along the banks of the Spokane River.