Retired Seattle prof is area’s dragonfly guru

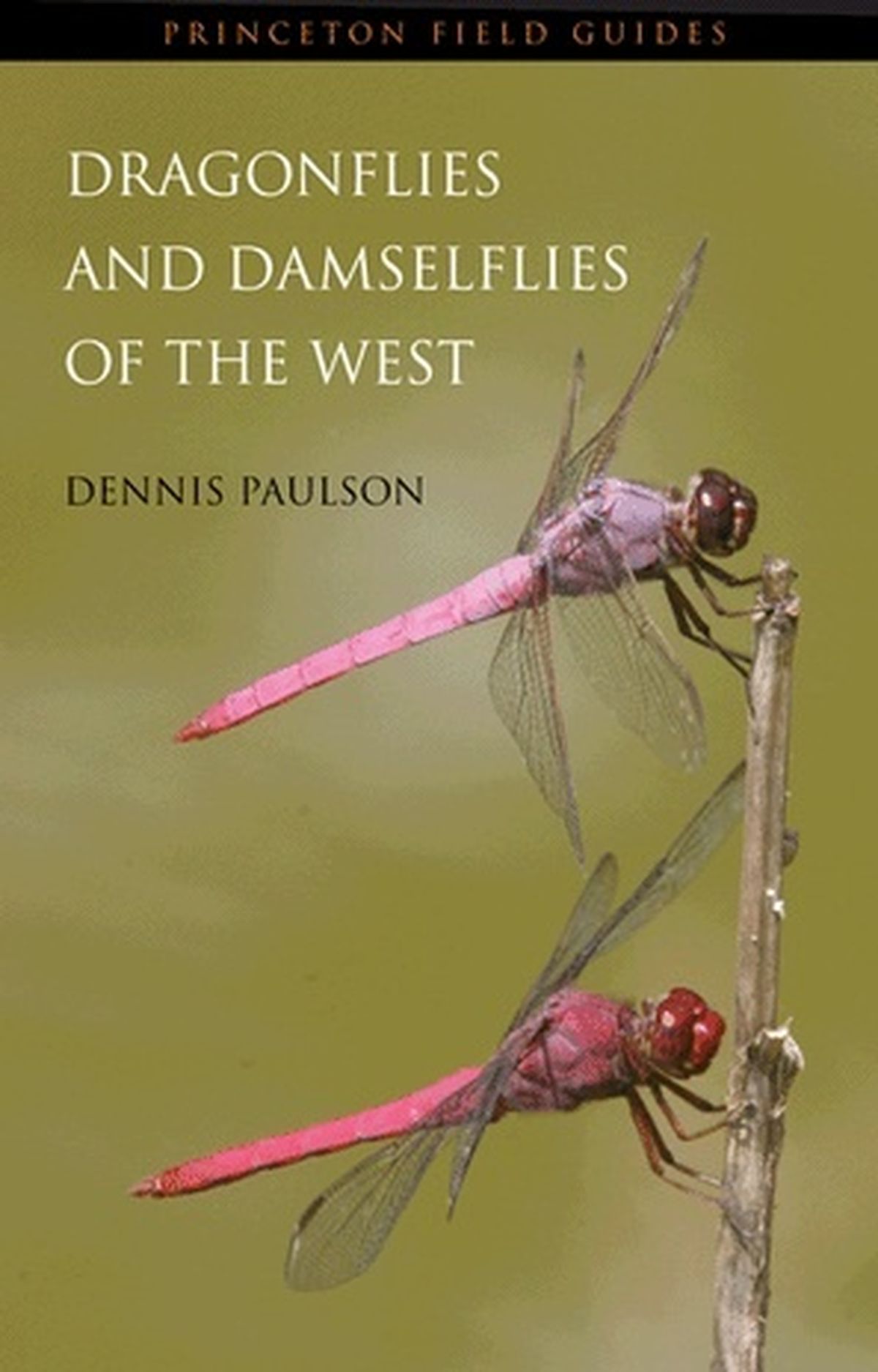

This field book by Dennis Paulson is the first fully illustrated field guide to all 348 species of dragonflies and damselflies in western North America. (Courtesy photo)

When they have questions about dragonflies, the region’s biologists and land managers have a go-to man in Seattle: Dennis Paulson, a retired University of Puget Sound biology professor, shorebird expert and guru of Odonata – the order of insects that includes dragonflies and damselflies.

“With about 6,000 species in the world, there’s always something to learn,” said Paulson, who most recently published, “Dragonflies and Damselflies of the West,” a guide to all 348 species of dragonflies and damselflies in western North America.

At least 80 species have been verified in Washington, where conditions are relatively poor for dragonflies, he said.

“We have the Northwest weather and a lot of dry country in between habitats,” Paulson said. “Some species inhabit only the Columbia Basin while some are found only at high elevations.”

Asked why the public should care, Paulson said, “I can’t explain the importance of dragonflies in an economic way. I just fall back on the idea that biodiversity is important.

“Plant and animal communities are held together by the complex web and number of species that live out there. If we got rid of all dragonflies or even sparrows or weasels, it probably wouldn’t be a good thing overall. Food webs are complex and important.”

If dragonflies were to disappear, dragonfly-eating birds likely would follow, especially in the tropics or specific areas where birds depend on dragonflies to get them through a portion of the year, he said.

“In Washington, merlins eat a lot of adult dragonflies during fall migrations; same with kestrels, eastern kingbirds and fly catchers.

“Perhaps more significant would be red-wing and yellow-headed blackbirds in some areas that live largely on dragonfly larva as they emerge from the water.”

Still-water fly fishermen know that dragonfly nymphs are important to fish – and anglers – but Paulson says ducks eat a lot of dragonfly nymphs, too.

The green darner – designated Washington’s official state insect in 1997 – is among the state’s fastest flying and most beautiful dragonflies.

Up to 3.5 inches long, it has silvery iridescent wings, bulbous compound eyes, emerald green thorax and a stripe of deep garnet running down the middle of a blue abdomen.

Paulson is intrigued by the dragonfly’s complex behaviors. “They’re territorial like birds,” he noted, “and their breeding behavior is unique.

“As the male transfers sperm from the end of its tail to the abdomen of the female, they fly around in a wheel-like position, both facing the same way when they fly. That makes them much more able to maneuver and escape other predators.

In contrast, he said, “Butterflies, hook up end-to-end making them clumsy in the air as they work out which direction to fly.

“Dragonflies are predators, which makes them more intriguing that a butterfly that flits from flower to flower,” he said. “They use their legs to scoop prey into their mandibles.”

Some species fly so well they can catch bald-faced hornets, one of the most aggressive insect predators. “We saw a dragonfly catch one and nip its head off, getting rid of the danger so it could enjoy its meal.”

Folklore has seized that sort of treachery. “The green darner dragonfly’s name comes from the myth that it could sew your eyelids shut,” Paulson said.