Bo Jackson’s magical 1989 All-Star game still resonates

KANSAS CITY, Mo. – My 11th birthday came in the spring of 1989, which means I wore striped socks up to my knees, had a huge crush on the lead singer of the Bangles and will fight anyone who disrespects “Back to the Future.”

Every stage of life brings its own gifts, you know. The independence of adolescence and the freedom of high school. The fun of college and the growth of young adulthood. But there is something magical about being an 11-year-old.

Things that happen at that age tend to stick with us, and hopefully what we’ll remember at the All-Star game two months from now in Kansas City will give another group of boys something they’ll remember a generation later when they’re married and trying to buy a house.

At 11, baseball cards cluttered my closet. Michael Jackson played on my boombox. I’d just discovered Nintendo. The best meal I could imagine was my mom making macaroni and cheese out of the box.

That’s an age grown enough to form your own opinions but young enough to be spared the cynicism. A sunny day means you can play outside longer, an ice cream cone means the world. Firefighters and astronauts and athletes are your heroes. Bo Jackson was my hero.

Bo took my breath away, and at 11 years old, there is nothing more important in the world. Bo was a cartoon character, is what he was. A Heisman Trophy winner who wanted to play baseball. A muscular guy who never lifted weights and ran faster than anybody else. A brutally raw hitter who would hit home runs people compared to Babe Ruth and strike out with a bat he’d usually break over his leg.

“I’m just another player,” he’d say, an obvious lie that just made the whole thing seem more magical.

Bo became a superhero. Frank White called him “Superman.” Bo hit the longest home run in Royals Stadium history in his first week on the job with someone else’s bat. He beat out routine grounders to second base. Years later, Bo said that when he was born God gave him “a built-in steroid.”

He ran up the outfield wall, hit 450-foot home runs in batting practice left-handed, became the most dynamic running back in the NFL in his spare time and, after an absurd, flat-footed, 300-feet-in-the-air rocket that is simply remembered as The Throw nailed Harold Reynolds at the plate in the 10th inning, heard Reynolds joke, “You need to pee in a cup.”

The Throw happened in May of 1989. This was, looking back, the height of his powers. Bo was 26 years old then and having his first truly outstanding baseball season. He would hit 32 home runs, drive in 105, and lead all big leaguers in All-Star voting. That fall, he rushed for a career-high 950 yards in the 11 games he played for the Raiders after baseball season.

But it’s the All-Star game I’m thinking of right now. To some of my friends, Bo was still a myth. Overrated. Struck out too much. Whatever.

“Wait until the All-Star game,” I remember one of them saying. “Then we’ll see if he’s really any good.”

I nodded my head yes. Battle lines drawn. I’d never looked forward to an All-Star game more, and haven’t looked forward to one as much since. The imagination of an 11-year-old sports fan is a powerful thing.

Nobody could figure out where Bo should hit. This became a major storyline in the run-up to the All-Star game. Tony La Russa decided to give himself the most explosive leadoff hitter in All-Star game history.

Bo had never led off a big league game before, so of course he watched the first pitch and hit the next one 448 feet over the center-field fence. One of the longest home runs the All-Star game ever saw. The ball bounced halfway up the green tarp the Angels set up as the batters’ backdrop. Tommy Lasorda, managing the N.L. that day, said it sounded like a golf ball.

“Luckily,” Bo would say, “I got a piece of it.”

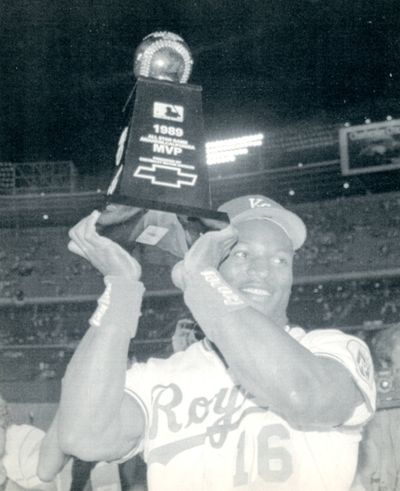

Bo became the second man to homer and steal a base in the same All-Star game that day, joining Willie Mays. He was a runaway winner for the game’s MVP, playing on a bad hamstring he didn’t tell anyone about.

This was 23 years ago this summer, long enough that some kids born that day are now college graduates, and not nearly long enough to lose one of the coolest memories of my life as a sports fan.

This summer, two months from now, perhaps a new class of 11-year-olds will watch something they’ll never forget in a baseball game in Kansas City.