Rethinking wilderness: Panhandle proposals would shift boundaries

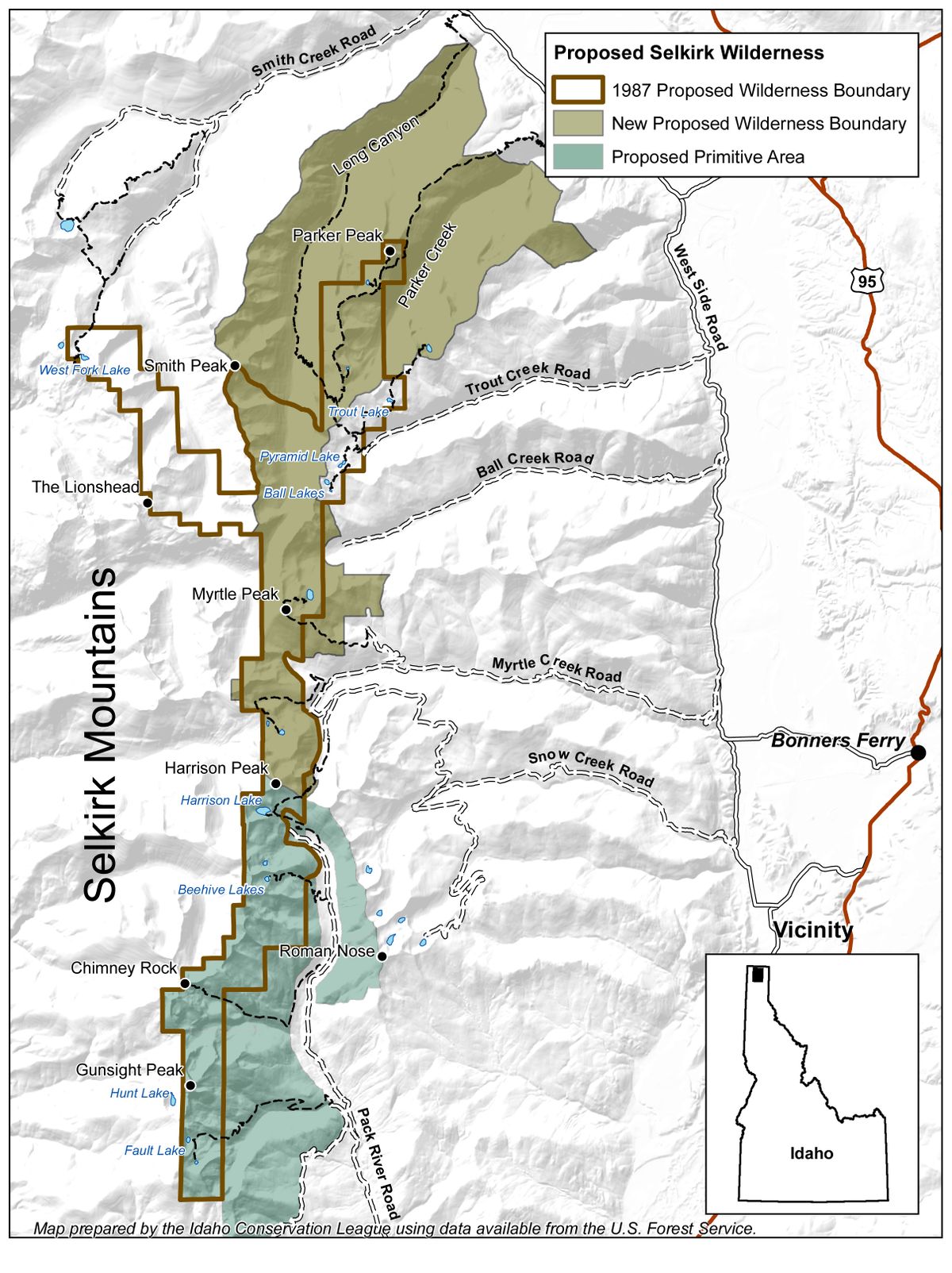

Idaho Conservation League map regarding the forest plan proposal for the Selkirk Mountains, revised. (Courtesy of Idaho Conservation League)

Wilderness is politically hard to sell in North Idaho, where national forest clientele seems to love or hate the concept.

Only Congress can designate wilderness. It’s the highest level of federal land protection, precluding roads as well as motorized vehicles and even mechanized equipment such as bicycles and chain saws.

No official wilderness has been designated in Idaho north of the Selway-Bitterroot. Yet, for decades, the U.S. Forest Service has guarded some pristine roadless areas as candidates for wilderness.

The 1987 Forest Management Plan covering 2.5 million acres of the Idaho Panhandle National Forests assured backcountry travelers and wildlife enthusiasts they would find wilderness values protected in choice areas, although the boundaries were disputed.

The proposed IPNF forest plan revision, released in January, recommends 139,300 acres in four areas for wilderness. The names of the areas remain the same, but the boundaries in some cases have changed dramatically.

The public has until April 5 to comment on adjustments that rose largely out of public meetings and collaborations in 2004-2005.

The four areas recommended for wilderness in the draft plan include:

• Scotchman Peaks, northeast of Lake Pend Oreille, 25,900 acres.

• Salmo-Priest, north of Priest Lake, additions to existing wilderness in Washington, 19,600 acres.

• Selkirk Mountains, the crest from Parker Peak south to Hunt Peak, 36,700 acres

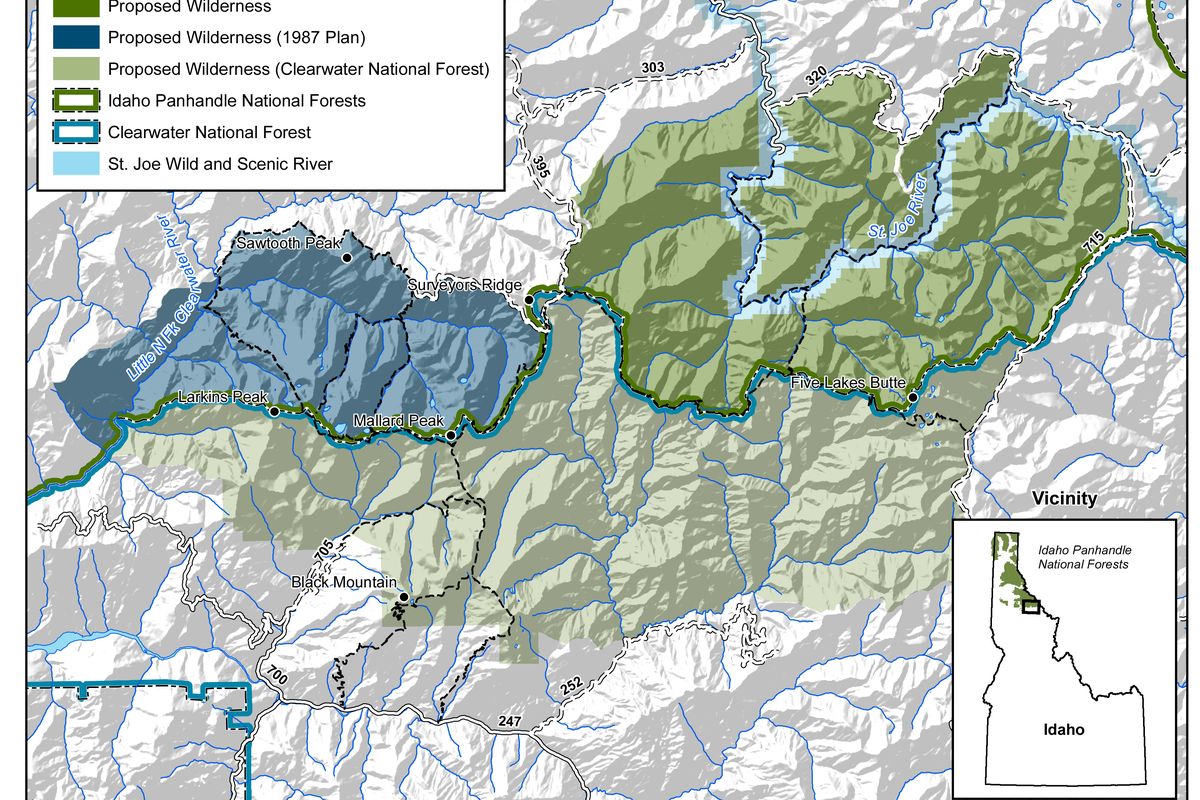

• Mallard-Larkins, from Spruce Tree Campground area up the St. Joe River roadless area to St. Joe Lake, 57,100 acres.

Changes for the Mallard-Larkins are among the most surprising to wilderness advocates. Indeed, Mallard-Larkins is a misnomer in the draft plan because the new proposals include neither Mallard nor Larkins peaks.

“We kept the name the same for continuity from the ‘87 plan, but I can see where it might be confusing,” said Kent Wellner, IPNF recreation manager and a leader on the planning staff.

The original Mallard-Larkins was designated a “Pioneer Area” in 1969 by regional forester Neal Rahm to offer special protection without the need for wilderness legislation. It’s been recommended for wilderness since the 1970s.

The draft plan continues protections for the upper St. Joe, prized by hunters and fishermen. But the area known as the Mallard-Larkins has been downgraded to a “special area” rather than a wilderness candidate, Wellner said.

This special area includes popular backpacking and horse packing destinations such as Mallard, Fawn, Northbound, Heart, Crag and Larkins lakes.

“There’s concern about the amount of proposed wilderness in that part of the world,” Wellner said.

A massive Great Burn Wilderness Area is being negotiated by the Clearwater Collaborative on the adjacent Clearwater National Forest, he said.

“Combine that with the wilderness recommended in the St. Joe upstream from Spruce Tree Campground, and it makes people who live in that area uneasy,” Wellner said.

The draft plan calls for no changes in the way the Mallard-Larkins is managed even though the wilderness recommendation is dropped.

“Motorized vehicles and mountain bikes would still be prohibited,” he said, “although chainsaws could be used to clear trails.”

Brad Smith, who’s been poring over the draft plan for the Idaho Conservation League, said the change in attitude toward the Mallard-Larkins could be troubling in the long term.

“Even if they continue to manage the area as is, not having a wilderness recommendation could hurt the Mallard-Larkins chances if wilderness proposals get introduced in Congress,” he said.

“We haven’t seen solid reasoning in the plan for excluding that choice chunk of the Mallard-Larkins.”

Chuck Mark, the St. Joe District Ranger during the years of public meetings, has left the position. Wade Sims, the new district ranger, could not be reached for comment last week.

“Combining all the information we gathered at the public meetings with the given laws, such as the 2008 Idaho Roadless Rule, we tried to be as responsive as we could to the communities we serve,” Wellner said.

Selkirk Mountains wilderness recommendations also are dramatically different from those made in 1987.

However, reasons for the changes are no mystery. They were driven by input from snowmobilers and mountain bikers.

The Forest Service preferred options would no longer suggest wilderness for Pack River drainage areas including Harrison Lake and Chimney Rock – areas coveted by backpackers as well as snowmobilers.

The Forest Service has recommended a “primitive area” designation for 19,730 acres, which would prohibit motorized use during summer, but allow over-show motorized recreation during winter. Primitive areas also allow mechanized equipment such as mountain bikes.

The change reflects the large increase in snowmobiling use in the region and the increased range of snowmobiles since the last plans were created in the 1980s.

“Even if the draft is approved as is, snowmobilers will continue dealing with restrictions on motorized use because of caribou habitat,” said John Finney Jr. of the Sandpoint Winter Riders snowmobile club.

“Right now the area’s closed to snowmobiling by the courts,” he said.

At the north end of the Selkirks, the draft recommends wilderness for an area neglected by the ’87 plan. The Long Canyon-Parker Ridge addition would help offer long-sought protection for the last two major unroaded drainages in the Selkirk Mountains.

Salmo-Priest wilderness recommendations include the Upper Priest River area, which has raised concerns among mountain bikers who would be forced off a favorite trail.

The rare old-growth cedars lining the Upper Priest River bottom give the area special value, Wellner said

“ICL sees the value of cherry-stemming wilderness in the Upper Priest so mountain biking can continue up the river corridor to American Falls while the surrounding area would remain recommended for wilderness,” Smith said.

On the other hand, the league does not support the forest service plan to leave the Hughes Ridge and meadows areas out of wilderness.

The ridge is important for caribou and the meadows are important for grizzly bears as they come out of hibernation,” Smith said.

All such factors and comments will be considered by the forest planning team after the April 5 comment deadline, Wellner said.

“This isn’t a done deal,” he said. “We welcome comments on the draft.”

Scotchman Peaks wilderness recommendations have changed slightly from 1987 to follow drainages more logically northeast of Lake Pend Oreille.

“The area, which crosses into Montana, has been a wilderness choice since the Forest Service started making the recommendations in the ’70s,” said Phil Hough, who helped organize the Friends of the Scothman Peaks Wilderness.

“There’s very high agreement in this region that this area should be wilderness for its scenic and wildlife values,” he said.

Said Wellner, “As far as the four wilderness areas proposed in the draft plan, the Scotchman Peaks group has been notably proactive in strong collaborative fashion with all user groups, government agencies, local governments and even congressional staff.”

“As far as the Panhandle is concerned, that would be the closest to being ready to consider for wilderness if Congress were to take it up.”