Kevorkian challenged views on life, death

DETROIT – Jack Kevorkian built his suicide machine with parts gathered from flea markets and stashed it in a rusty Volkswagen van.

But it was Kevorkian’s audacious attitude that set him apart in the debate over doctor-assisted suicide. The retired pathologist who said he oversaw the deaths of 130 gravely ill people burned state orders against him, showed up at court in costume and dared authorities to stop him or make his actions legal. He didn’t give up until he was sent to prison.

The 83-year-old Kevorkian died Friday at a Michigan hospital without seeking the kind of “planned death” that he once offered to others. He insisted suicide with the help of a medical professional was a civil right.

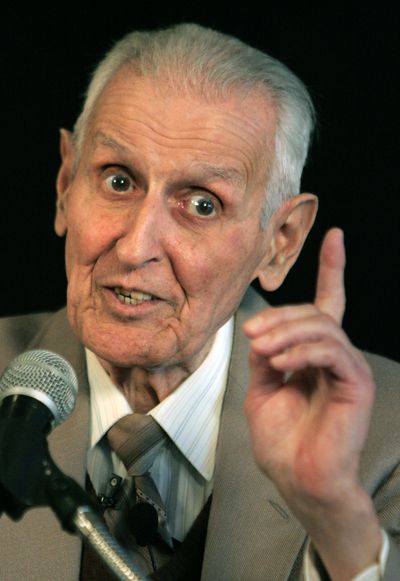

His gaunt, hollow-cheeked appearance gave him a ghoulish, almost cadaverous look and helped earn him the nickname “Dr. Death.” But Kevorkian likened himself to Martin Luther King Jr. and Gandhi and called physicians who didn’t support him “hypocritic oafs.”

“Somebody has to do something for suffering humanity,” he once said. “I put myself in my patients’ place. This is something I would want.”

Kevorkian died at William Beaumont Hospital in Royal Oak, where he had been hospitalized since May 18 with pneumonia and kidney problems. He suffered from a blood clot that traveled up from his leg, according to attorney Mayer Morganroth, who was present and said his friend was “totally in peace, not in pain.”

“His medical directive was not to be given any CPR or continuing life program.” Morganroth said.

Kevorkian’s flamboyant former attorney, Geoffrey Fieger, believes Kevorkian would have taken advantage of doctor-assisted suicide if it had been available.

“If he had enough strength to do something about it, he would have,” Fieger said Friday. “Had he been able to go home, Jack Kevorkian probably would not have allowed himself to go back to the hospital.”

The former prosecutor whose office convicted Kevorkian of second-degree murder said he found a trace of hypocrisy in Kevorkian’s death.

“I assumed that someday he’d commit suicide and tape it and air it for the world to see,” said David Gorcyca, who oversaw prosecutions in the Detroit suburbs of Oakland County.

Those who sought Kevorkian’s help typically suffered from cancer, Lou Gehrig’s disease, multiple sclerosis or paralysis.

He catapulted into the public eye in 1990 when he used his machine to inject lethal drugs into an Alzheimer’s patient. He often left the bodies at emergency rooms or motels.

For much of the decade, he escaped legal efforts to stop him. His first four trials, all on assisted-suicide charges, resulted in three acquittals and one mistrial. Murder charges in Kevorkian’s first cases were thrown out because Michigan had no law against assisted suicide. The Legislature wrote one in response. He also was stripped of his medical license.

“The issue’s got to be raised to the level where it is finally decided,” Kevorkian said during a broadcast of CBS’ “60 Minutes” that aired the videotaped death of Thomas Youk, a 52-year-old man with Lou Gehrig’s disease.

He challenged prosecutors to charge him again, and they obliged with second-degree murder charges.

Kevorkian’s ultimate goal was to establish “obitoriums” where people would go to die. Doctors there could harvest organs and perform medical experiments during the suicide process. Such experiments would be “entirely ethical spinoffs” of suicide, he wrote in his 1991 book “Prescription: Medicide – The Goodness of Planned Death.”

Kevorkian was freed in June 2007 after serving eight years of a 10- to 25-year sentence. His lawyers said he suffered from hepatitis C, diabetes and other problems, and Kevorkian promised in affidavits that he would not assist in any more suicides if released.

In 2008, Kevorkian ran for Congress as an independent, receiving just 2.7 percent of the vote in his suburban Detroit district. He said his experience showed the party system was “corrupt” and “has to be completely overhauled.”

Born in 1928, in the Detroit suburb of Pontiac, Kevorkian graduated from the University of Michigan’s medical school in 1952 and went into pathology.

Kevorkian’s life story became the subject of the 2010 HBO movie “You Don’t Know Jack,” which earned actor Al Pacino Emmy and Golden Globe awards for his portrayal of Kevorkian.

Kevorkian’s fame also made him fodder for late-night comedians’ monologues and sitcoms. His name became cultural shorthand for jokes about hastening the end of life.

Adam Mazer, the Emmy-winning writer for “You Don’t Know Jack,” got off one of the best lines of the 2010 Emmy telecast.

“I’m grateful you’re my friend,” Mazer said, looking out at Kevorkian. “I’m even more grateful you’re not my physician.”