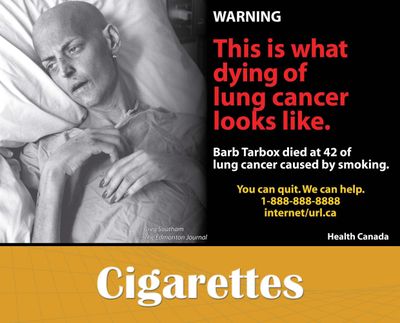

Cancer victim’s deathbed image sends message to smokers

She was Barb Tarbox, and she died on May 18, 2003, of lung cancer at the age of 42. From October 2002, two months after she was diagnosed, to the moment of her death, the Edmonton, Alberta, homemaker set about making her ordeal a lesson to others about the dangers of smoking.

In her final months, she maintained a punishing schedule of public speeches to schoolchildren and teen groups, and allowed the local newspaper to chronicle her slide toward death.

A photograph taken five days before Tarbox died was one of 36 possible warnings the Food and Drug Administration considered in the run-up to last month’s unveiling of nine graphic messages that must be on the cover of every cigarette pack sold in the United States starting fall 2012.

The fine print of the FDA’s final ruling notes that among all the images considered, the photograph blandly dubbed by regulators “deathly ill woman” was among the most widely recalled by adults and high schoolers in tests. But it was not among the nine that made the cut.

Some scientists who study how public health messages work – and don’t work – to make people change their behavior were disappointed by the FDA’s decision. Others professed relief.

Both camps, however, agreed that such emotionally laden images will be a powerful weapon going forward in moving smokers to give up the habit and swaying others to not start.

For all the power of facts, people do not react to health messages with cold, hard reason; they respond to them emotionally, says Paul Slovic, a pioneer in the field of health communications at the University of Oregon.

When smokers are confronted with an image that makes them feel unlovable, unhealthy, unappealing or ashamed – and they link those feelings to their cigarette habit – they will, he says, be primed to quit.

The “ugly, disturbing image” of a cancer patient at death’s door, Slovic adds, is a perfect counter to tobacco advertising, which for decades has depicted attractive people engaged in fun activities with cigarettes in hand – sitting around a bonfire on the beach, sharing a laugh with a friend over coffee, strolling through a meadow in bloom.

• • •

Barb Tarbox could have been a model in one of those ads. Six feet tall and willowy, with a head of honey hair and fierce blue eyes, she picked up gigs as a runway model while living in Ireland in her early 20s, then back in Canada when she returned to help care for her mother, who died of smoking-induced lung cancer at 46.

Tarbox was quick with a laugh and even quicker with a cigarette. She started smoking at age 11 and didn’t stop when doctors warned she faced a higher-than-normal risk because of her family history.

At the time of her diagnosis, she was a two-pack-a-day smoker, says her husband, Pat Tarbox, a 53-year old restaurateur in Calgary who has since remarried.

She was a devoted mother of three, including a baby, Patrick, who died two weeks after his premature birth, and his twin, Michael, who was diagnosed with autism and died suddenly of a heart defect at 8.

Her daughter Mackenzie was 9 when Tarbox died, and has just graduated from high school. Pat Tarbox says his wife was wracked with guilt that she had allowed cigarettes to leave Mackenzie motherless.

Within a month of learning that the cancer had spread to her brain and neck and was inoperable, she took her shame and grief on the road. Criss-crossing Canada, she warned any group that would invite her about the health consequences of smoking.

She was particularly keen to confront young teens with her story, knowing that many had already been – or would soon be – tempted to start smoking, but might not yet be addicted.

“Her message was hard. It was, ‘Look at me: This is what can happen to you,’ ” says Bruce Buruma, executive director of an educational foundation that organized Tarbox’s most well-attended speech, which packed some 5,000 kids into a hockey arena in the Alberta city of Red Deer. “She had a gift for talking to kids.”

She would saunter across the stage – when she still could saunter – with an unlit cigarette and a big hat and tell kids they were looking at “the biggest idiot in the world.”

Always vain about her shoulder-length mane, she would draw listeners in with tales of the life and looks she had before her diagnosis. Then with a flourish, she’d snatch off her hat or wig and stand bald and gaunt before a stunned audience.

“She would throw herself in front of a bus to help a kid, and if she could just get one kid to stop smoking, she always said, it’d all be worth it,” Pat Tarbox says. “But she did not varnish the truth.”

• • •

Tarbox was just as unflinching with Greg Southam, the Edmonton Journal photographer who, near the end, often balked at recording images of the wraith he had grown to know and admire.

“She urged Greg not to worry about that stuff,” says Pat Tarbox. “The pictures were pretty graphic and people shied away from them. But she knew those pictures would speak volumes after she was gone.”

But whether exposure to such unvarnished truth can persuade a person to change his or her behavior is a key, and much debated, question.

There is a fine line between images that are striking and memorable and images that are so disturbing or outlandish that they undermine the credibility of the intended message, or leave people too discouraged to change, says Joseph Cappella, a health communications researcher at the University of Pennsylvania.

Tarbox’s deathbed picture went too far for some who offered their feedback to the FDA.

“Some comments noted that the image ‘offend(s) against human dignity,’ while one stated that it was ‘too sensational to be effective,’ ” the FDA reported in its final ruling.

In choosing its first round of images – a fresh crop may be chosen in as little as a year – the FDA focused heavily on how well they meshed with text messages that were dictated in advance by Congress: “Cigarettes cause strokes and heart disease,” for example, and “Tobacco smoke causes fatal lung disease in nonsmokers.”

The result is a mixed bag of images. Some encourage (a tough-guy rips open his shirt to reveal an “I Quit” message on his T-shirt beneath). Some are cautionary (a well-dressed heart attack victim’s shirt and tie are undone as he is administered oxygen). Some make you wince (lips ravaged by cancer frame a mouthful of rotting teeth).

None shocks the way Barb Tarbox’s image does.

In FDA tests, “deathly ill woman” scored highly with adults, young adults and youth on scales of emotional impact, comprehension of the warning’s message and the “difficult-to-look-at measure.”

But regulators ultimately concluded that the image they called “cancerous lesion on lip” was a better vehicle for the message “Cigarettes cause cancer.”

The FDA’s first round of choices are not unlike the first round of graphic images required by Canada, which pioneered use of cigarette-pack warnings in 2001.

In December, the Canadian government ordered a fresh round of images for cigarette packs sold there, and selected the photo of Tarbox as one of them.

The warning being considered by Canada would wring far more emotion from the image than the FDA’s “Cigarettes cause cancer.” It will read, “This is what dying of lung cancer looks like.”

Tarbox’s picture “was the one I had most hoped the United States would adopt,” says psychologist Geoffrey Fong of Ontario’s University of Waterloo, who has studied the impact of warning labels in Canada and many of the 40 countries that preceded the U.S. in requiring them.

• • •

In her last eight months, Tarbox spoke before audiences totaling at least 50,000, and many more if you count those who heard and saw her on radio and television.

Among the latter, recalls Pat Tarbox, was a grizzled long-haul trucker who later told Barb’s family that after listening to her on the radio, he threw his cigarettes out the window and never smoked again.

Southam, who took the picture of Barb Tarbox on May 13, 2003, well remembers the first time he saw it. The photograph, taken in the last days of film, had been developed, and he and Edmonton Journal reporter David Staples wandered down to the photo room to take a look at the day’s shots.

When the image popped up on a computer screen, both men fell silent.

“I said to Dave, ‘You’ve got to turn that off. I can’t stand to look at it,’ ” Southam recalled.

Staples remembers thinking, “We should destroy that. We could never run that. This is wrong.”

And then the two men remembered that this is what Tarbox had asked for: the truth.

“It might get a little annoying after a while for a smoker to look at that,” Southam says. “I hope it does. That was Barb’s