Mange study trims wolves

Wolves dying from hair loss in Yellowstone helps researchers understand ravages of scabies

Paul Cross found out it takes about five people to hold down an adult gray wolf for a shave.

The disease ecologist with the U.S. Geological Survey in Bozeman was cutting a patch of hair off a captive wolf in the Grizzly and Wolf Discovery Center in West Yellowstone this winter as part of a study he’ll carry over to Yellowstone National Park this month.

Wolves are not hunted in Yellowstone, yet some of them are dying from the effects of mange, also known as scabies.

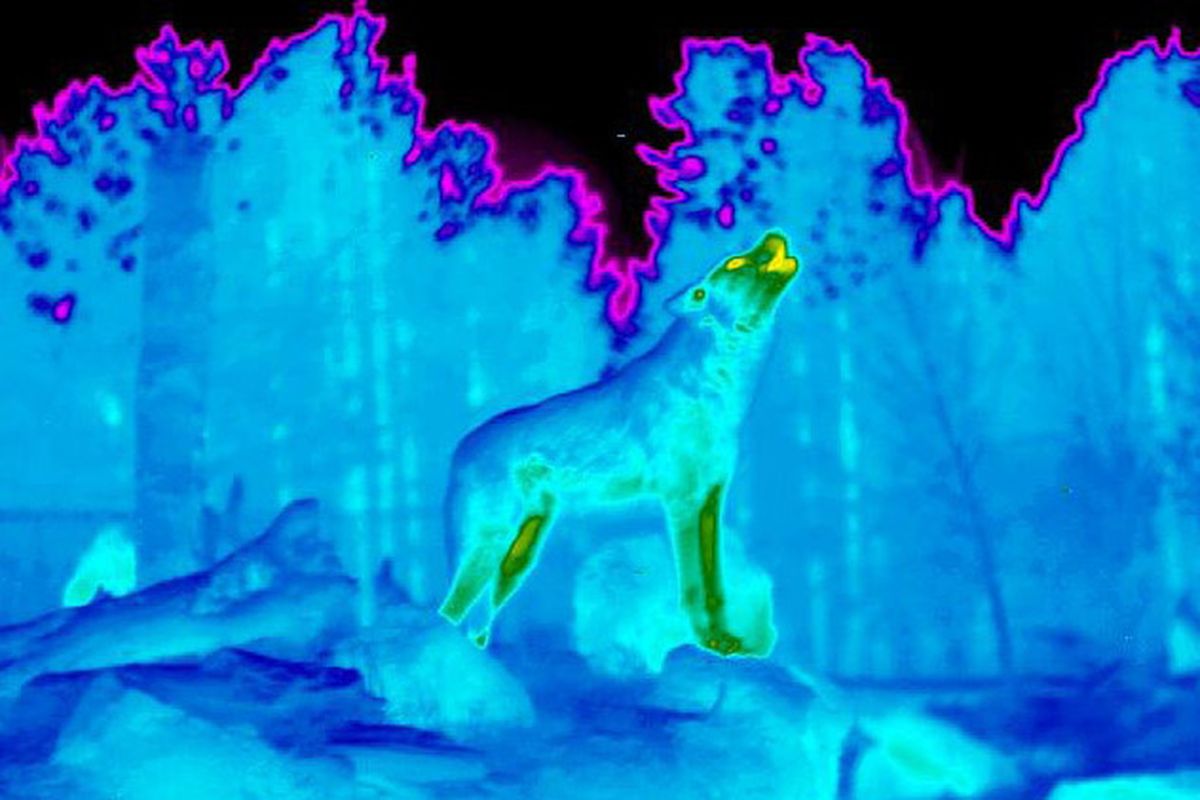

By using remotely triggered thermal-imaging cameras, Cross is hoping to get a better idea of how sarcoptic mange affects wolves in the park. Shaving the wolf in the Discovery Center allowed Cross to get some baseline data.

“Not much is known about mange,” said Doug Smith, Yellowstone’s wolf biologist. “We think it’s affecting the size of the population.”

Smith said the study will help park officials and the public better understand how disease affects the animals. The research is being conducted by the USGS Northern Rocky Mountain Science Center and the National Park Service, Yellowstone National Park and the Grizzly and Wolf Discovery Center.

“Five years ago, disease wasn’t even on the list of what kills wolves,” Smith said.

Four, possibly five, of the 10 packs in the park have wolves recently identified with cases of mange, but none has a bad case, Smith said.

Recent aerial counts estimated 110 wolves in 10 packs are roaming the park. That’s up slightly from last year when 96-98 wolves were counted in 14 packs.

Cross is interested in how outbreaks of mange in wolves affect a pack’s social dynamics, cohesion and a wolf’s status, how many wolves survive infection and what are the caloric costs of losing much-needed insulating fur during the winter.

Does the disease stay in the system, and at what level? He’s also interested in whether the thermal imaging cameras can detect mange more quickly.

Although the two-year study could provide interesting insights into the role mange plays in wolf packs, Cross said there is no plan to use the study as a way to help infected animals.

“In general, we have very limited tools to do anything about any wildlife diseases,” he said.

Mange was first observed in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem around 2002, Cross said. That’s seven years after wolves were reintroduced to Yellowstone Park.

By 2007 the disease was infecting park wolves, peaking in 2009. Along the way, it is believed to have aided in the downfall of the park’s most dominant pack in the Northern Range – the Druid pack which winked out in 2010.

Meanwhile, Mollie’s pack, which forages in the interior of the park, contracted one of the worst cases of mange Smith had seen, yet the pack stayed intact.

“We don’t know what’s driving the difference,” Cross said.

This month, Cross will set up two thermal-imaging cameras along with other remotely activated digital cameras inside Yellowstone. The thermal-imaging cameras are being built by Montana State University engineers specifically for the project. The cameras will record the temperature of the animals photographed and save it onto a memory card. Those images can be collected weekly and downloaded to a computer for viewing.

Wolves are so well insulated that when resting on the ground in the evening, they are hard for the thermal-imaging camera to differentiate from a rock, Cross said.

“Like many cold-adapted animals, they’re very good at insulating,” he said.

Once the wolves start moving around, the camera picks up heat signatures coming from the wolves’ eyes and legs.

Shaving patches in a few captive wolves helps the researchers make sure what their equipment should be detecting in the field, he said. “And it gives us a baseline of healthy skin to compare to the infected wolves.”

Cross theorizes that infected wolves will have to increase their food intake to compensate for a loss of fur.

“We expect them to have to kill more to supplement their energy costs,” he said.

On the flip side, the wolves may be less efficient hunters because of the loss of fur. He’s also wondering if other wolves in the pack will help nurture a sick wolf by sharing food, or is it simply survival of the fittest.

Studying sarcoptic mange in wolves in Yellowstone provides a unique opportunity, Cross said

“It’s a visible disease in a visible wildlife population,” he said. “We’ll get information here that we won’t get anywhere else about mange.”