Study tracks reasons behind high rate of illness near Northport

Focus is area downstream from B.C. smelter

Gail Leaden was 5 when she was diagnosed with ulcerative colitis. In high school, Leaden’s best friend in the small town of Northport, Wash., was diagnosed with the same illness.

She always found the coincidence odd.

“It’s not a common disease to begin with,” said Leaden, 25, who now lives in Spokane. “How ironic that my best friend gets it.”

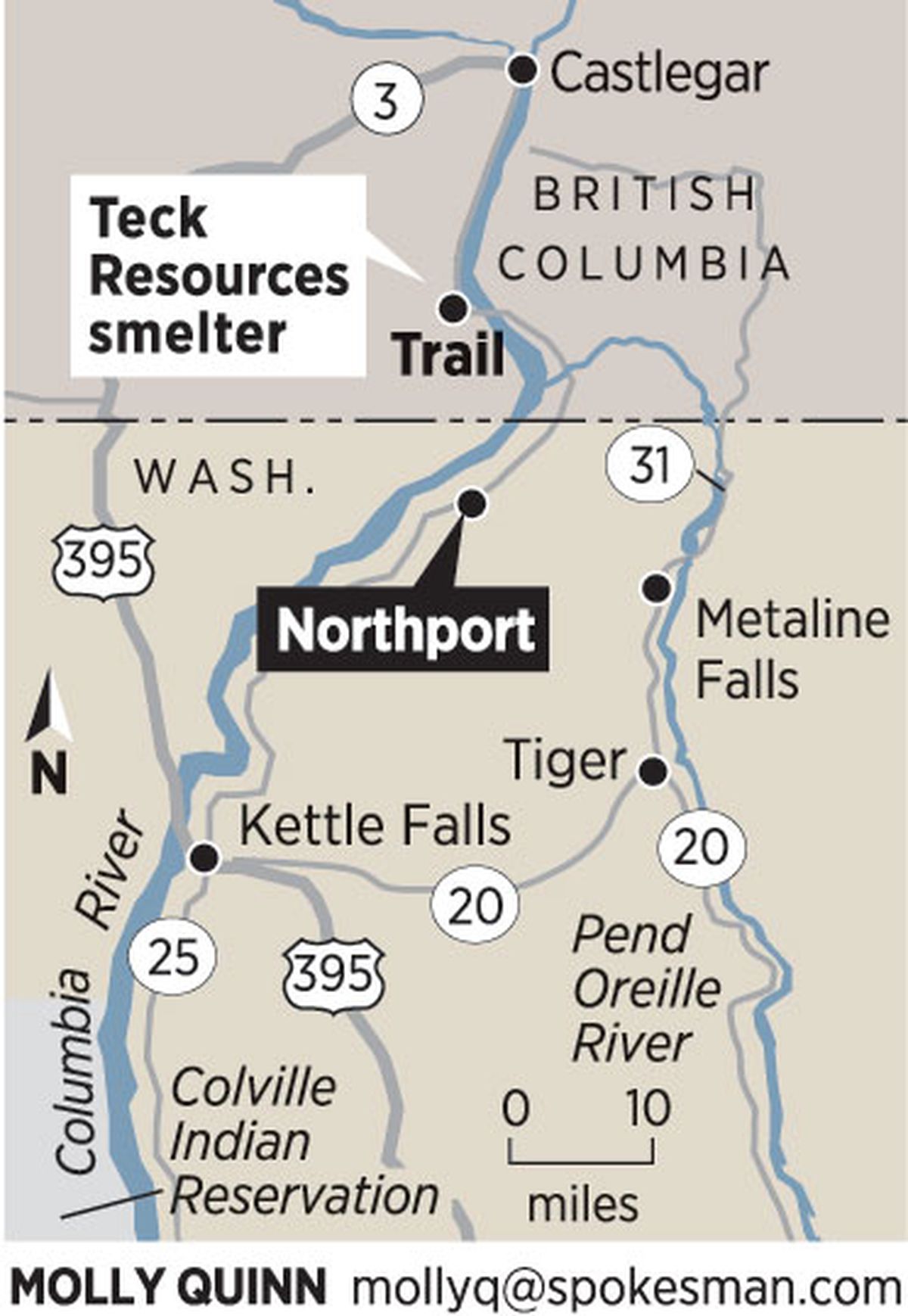

More than 50 residents or former residents of Northport say they’ve been diagnosed with ulcerative colitis or Crohn’s disease, two types of inflammatory bowel disease. Some suspect that their health problems are tied to decades of industrial emissions from a smelter in Trail, B.C. An upcoming study may eventually provide answers.

Two doctors from Boston’s Massachusetts General Hospital are looking into reports of high rates of bowel disease in Northport, a town of 330 near the Canadian border. In the general population, about 4 people per thousand are diagnosed with Crohn’s or colitis.

“We should be expecting to see one or two cases for a town the size of Northport,” said Dr. Sharyle Fowler, who will be working on the study.

The disease cluster, if it can be confirmed, could shed light on triggers for Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis, said Dr. Josh Korzenik, director of Massachusetts General’s Crohn’s and Colitis Center. No one knows what causes the diseases, which affect 1.5 million Americans, but both appear to have genetic and environmental contributors.

“We were drawn to this because it’s an unusual cluster, or potential cluster, in a small population,” Korzenik said. “It offers us both a potential opportunity to help the people of Northport, as well as a much broader group of people, by understanding some of the environmental components that may lead to these diseases.”

Rates of Crohn’s disease and colitis are on the upswing in industrialized countries. People with the disease often have persistent abdominal pain and diarrhea. Surgery is sometimes required.

The doctors’ first step is to determine whether they can confirm anecdotal reports of a disease cluster. They’ll send out health questionnaires to current and past Northport residents. They’ll also ask people’s permission to review medical records.

“If there is an increased risk of these diseases in Northport, this may be the first step of a longer pursuit of trying to understand why,” Korzenik said.

Future studies could look at pollution exposure to see if it correlates to illness rates, he said. Or, the studies might investigate whether Northport has an unusual, but genetically explained cluster, he added.

That type of testing would require research funding. At this point, Korzenik said, the health questionnaire is a “sweat equity” effort by the two doctors, who were intrigued by health histories collected by local volunteers. About 320 current and former Northport residents provided health information. Thirty-six said they had ulcerative colitis; 18 said they had Crohn’s disease.

Smelter stopped dumping slag in ’95

Jamie Paparich suspects a link to the smelter. Her grandparents raised six children on a farm outside of Northport, about 15 miles downwind and downstream of the smelter owned by Teck Resources Ltd. For decades, the century-old smelter released tons of pollution daily into the air and the Columbia River, including mercury and other heavy metals.

The Washington Department of Health put an air monitoring station on the Paparich property. Through the 1990s, it recorded elevated levels of arsenic and cadmium, said Paparich, who lives in Nevada.

Both her dad and her aunt, who grew up on the farm, were diagnosed with ulcerative colitis. They ate vegetables from the family’s garden and swam in the Columbia River. As the disease progressed, both siblings had their colons removed.

Two neighboring families also had children with colitis and Crohn’s disease, said Rose Kalamarides, Paparich’s 54-year-old aunt.

The families “weren’t related by any stretch, yet we all had these same problems,” said Kalamarides, who now lives in Anchorage, Alaska.

In the early 1990s, the state Department of Health found significantly higher rates of hospitalization for inflammatory bowel disease in Stevens County and adjacent counties compared with the rest of the state.

A few years later, the federal Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry prepared a Northport public health assessment. Results were inconclusive, but the study generally found that pollution didn’t reach concentrations known to cause health problems.

“Our understanding is that these studies have not linked the elevated incidence of inflammatory bowel diseases … with any specific causes,” said Richard Deane, Teck’s manager of energy and public affairs.

Another study done in Trail, B.C., didn’t find higher hospitalization rates for bowel disease compared with the rest of the region. That study was done in 1994 for the B.C. Ministry of Health.

Deane said the smelter has cleaned up its act. In 1995, the smelter stopped dumping slag, a byproduct of the smelting process, into the Columbia River. Slag contains 25 compounds, including heavy metals. The smelter also halted production of phosphate fertilizer, reducing mercury releases into the river.

Heavy metals releases into the air and water have dropped by 95 percent as Teck has invested in upgrading the smelter, Deane said. Through an agreement with the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Teck also is paying for a multiyear study of pollution in the upper Columbia. The studies will look at current contaminant levels and whether they pose threats to people or wildlife.

“Those studies will cover Northport,” Deane said.

‘Something’s not right’

Northport residents, however, have long lobbied for epidemiology studies, which would take a closer look at disease rates.

Paparich got active in the effort three years ago, after stumbling across the air monitoring results for her grandparents’ farm. She contacted the national Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation last year, which put her in touch with Korzenik and Fowler.

She hopes that Northport can lead researchers closer to detecting the illnesses’ cause. Bowel disease is “an embarrassing, hard, painful illness,” Paparich said. “It really affects people’s quality of life.”

Said Kalamarides, Paparich’s aunt, “I’m curious whether anyone can really establish what happened.”

Though Kalamarides lives in Alaska, she returns to Northport frequently to visit her mother. She admits to feeling some trepidation about the controversy the study could unleash in Northport, which has close ties to Trail.

“Trail is a company town. A lot of people get real defensive because it could affect their livelihood,” Kalamarides said. “Even those of us who experienced the illness – I use a catheter to use the bathroom – are sensitive about it.”

Northport resident Barb Anderson thinks the community needs answers.

“I was counting up all the people I know with Crohn’s disease and colitis just the other day,” she said. “I came up with 15 people.”

The list includes her daughter, Kelsey Anderson, a graduate student in Seattle. Kelsey – Gail Leaden’s friend – was diagnosed with ulcerative colitis during her junior year of high school. At Rockwood Clinic in Spokane, where the diagnosis was made, doctors were surprised that two of Kelsey’s classmates had the same illness, said Barb Anderson. Leaden also remains troubled by the coincidence. It makes her suspect “that something’s not right.”

“I hope they can find an answer,” she said. “Was there a cause behind it, or was it a fluke?”