Gift of life

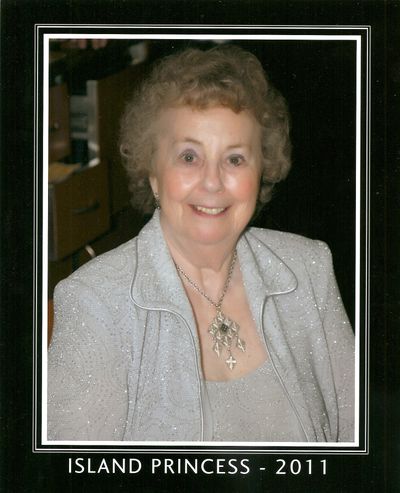

What began as a dream cruise for Spokane’s Vivian Marx became a medical nightmare after a near-drowning accident

“I was supposed to live to save her,” she says, touching the arm of her mother, Vivian Marx.

And then Fruci cries. Her mom does, too.

This Christmas day tale is part tear-jerker, part horror story – and many parts miracle.

It began the second week in October when Marx, 81, along with a dozen friends from Fairwood Retirement Village in north Spokane, boarded a cruise ship in Florida headed for the Panama Canal. On Oct. 13, the ship docked in Aruba. Marx signed up for an island excursion that included snorkeling.

But Marx had never snorkeled before. Yes, she says now, even 81-year-olds feel peer pressure.

“My mouthpiece didn’t fit, and I didn’t know how to work the fins,” she said. “I got saltwater in (the mouthpiece). That panicked me. Finally, I just got exhausted. The last thing I remembered was looking down and here was this fish and it was like looking into a fishbowl.”

A few hours later, Fruci, 56, who visiting a friend in Oakland, Calif., received a phone call from the Fairwood activities director. She told her that Marx was found floating face-down, her snorkeling equipment beside her.

An off-duty emergency room nurse and doctor who happened to be on the beach that day did CPR for 25 minutes. It finally worked.

Marx sat up on the beach and asked, “What’s going on?”

She was taken by ambulance to the hospital in Aruba. When Fruci talked to her mother by phone “she sounded normal,” Fruci said.

Marx’s travel companions returned to the cruise ship. The ship waited an extra hour so Marx’s belongings could be taken off the ship for later transport to the hospital.

Marx’s companions thought she would be kept under observation for a day or two, and then somehow catch up to the cruise ship.

But when people experience a near drowning, complications don’t often present for several hours. Saltwater insidiously irritates and compromises the lungs; infections set in. The body retains fluid. Organs can shut down.

Within 24 hours, the Marx siblings – Michael, Marie, Martin and Jeannine – knew their mom was in deep trouble. She could barely breathe when she spoke with them on the phone.

Fruci caught a red-eye from Oakland to Atlanta and then onto Aruba, landing on the Caribbean Sea island Oct. 16.

The nurses had warned Fruci that she would not be allowed to see her mother until the evening visiting hour. But the on-duty doctor took mercy on her, and Fruci was secreted into the room.

Marx was on a ventilator, heavily sedated and swollen from fluid retention.

“My mother looked like the Michelin man,” Fruci said. “I didn’t recognize her. I absolutely thought she was going to die.

“I just started whispering in mom’s ear: ‘I’m here. I’m taking you home.’ She started crying, so I knew she heard me.”

Next mission: Get Mom out of Aruba.

Fruci’s sister, Marie, is a former flight attendant whose friends own an air medical evacuation company in the Southwest. The company grandfathered Marx a membership, which slashed the cost of the air evacuation from $35,000 to $18,000.

Fruci’s mom became the talk of Aruba. A taxi driver begged Fruci not to tell the near-drowning story, because “tourism is our only industry.”

The owner of the snorkeling company tracked down Fruci, worried that family members would sue. (They won’t.)

By Oct. 18, all was ready for the air evacuation to Miami. A nurse handed Fruci a bill.

Fruci said, “No, you have to bill my mom’s insurance.”

An administrator then appeared.

“She explained that I have to pay my mother’s bill in full, or they cannot release (her),” Fruci said.

“I said, ‘What would happen if I couldn’t pay?’ She said, ‘Your mother would stay here.’ ”

Fruci called her husband in Spokane. Dave Fruci said, “Pay the bill.”

Fruci handed the administrator a credit card. The charge? Nearly $14,000.

When the medevac plane – staffed by a doctor and two respiratory nurses – landed at Jackson Memorial Hospital in Miami nearly three hours later, Fruci sobbed with relief.

Marx perked up immediately. Still ventilated, she used an alphabet chart to tell her daughter to find a substitute for her on the Fairwood bowling team.

Marx weaned off the ventilator quickly. She and Fruci flew home to Spokane on Oct. 27, two weeks after the near drowning.

Marx then recovered at the Fruci’s home in north Spokane and moved back to her Fairwood apartment just a week ago. Lingering symptoms? A nagging cough and physical balance issues.

Mother and daughter are counting blessings this holiday.

Dave and Jeannine Fruci have deep Spokane roots. High school sweethearts, they hail from big Catholic families, and are well-known in the business and art worlds here.

News of Marx’s near tragedy spread by word of mouth in Spokane and through Fruci’s Facebook page, where she keeps in touch with 547 friends.

Fruci is grateful for those friends’ prayers, and for her husband, Dave, who handled many of the logistics stateside with his usual competent calm.

She is grateful for her two grown daughters who kept her laughing. (They have nicknamed the adventure: “Aruba Gone Wild.”)

Fruci is also grateful for her siblings.

“Even though I was the only one physically there in Aruba, they were all living it and going through it, too,” she said.

The family greatly appreciates the excellent medical care in Miami, as well as the long-distance help Marx’s doctors provided from Spokane.

Marx is grateful that she doesn’t really remember anything from the fishbowl moment until “waking up” in Miami.

“In Aruba, just faintly, I remember Jeannine,” Marx said. “I knew then I was going to fight to live.”

Fruci was born an RH factor baby, a blood-type condition now easily cured, but life-threatening 56 years ago when blood transfusions were first used to cure it.

The doctor told Fruci’s parents: If you get a call in the middle of the night, plan a funeral. If not, you have your daughter.

Marx continues her physical recovery and is relieved that her travel-insurance policy, coupled with her secondary medical plan, reimbursed the family for medical costs they paid out of pocket.

Fruci, meanwhile, works on her emotional recovery.

In the journal where she’s chronicling the Aruba ordeal, Fruci has a question for the God whose birth the family will celebrate today.

She asks: “So God, how do you do it? I only had one life in my hands I was trying to save. You have them all. I can’t fathom it.”