In digital age, women retell family history via traditional sources

Around New Year’s Day 1958, the sailboat Revonoc went missing in a Florida storm.

Sarah Conover’s parents and grandparents were on the sailboat. Conover was just 18 months old; she and her older sister had stayed behind with babysitters in their Connecticut home.

Conover is now 55. The Spokane woman, author of six books, is now writing a book about the tragedy, and its aftermath in her extended family. The sailboat’s dinghy was eventually found 80 miles north of Miami, but no bodies were ever recovered.

Conover has plenty of primary material – as historians call it – to draw from. She possesses magazine and newspaper articles and letters. And she has a living historian, Frances Conover Church.

Church, 88, is Conover’s paternal aunt. She raised Conover and her sister after the tragedy and eventually adopted the girls.

Historians writing about Pearl Harbor Day – commemorated Wednesday – drew from primary material, such as newspaper accounts, letters and journals.

So how will public – and family – histories be written in a future when no one writes letters? Or keeps handwritten journals? When newspapers and magazines shrink or die altogether?

“I am absolutely worried,” said Dale Soden, history professor at Whitworth University.

Frances Conover Church was 35 when her brother and sister-in-law – Sarah Conover’s parents – were lost at sea.

Church also lost her own mother that day, and her father, Harvey Conover, who was 65.

Church’s father died without ever sharing his World War I adventures.

“We did see his medals,” Church said. “But he didn’t say why he got them.”

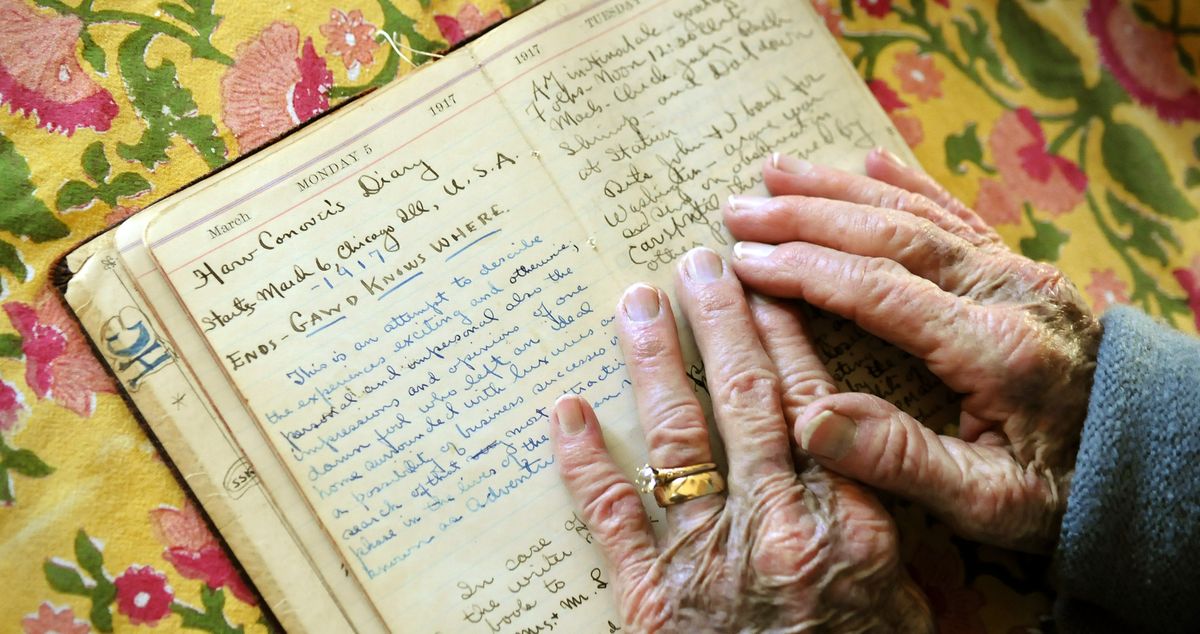

One day in the 1980s, Church was rummaging through a box of books that belonged to her father. She found three handwritten diaries dated 1917 and 1918. Her father’s war memories.

Harvey Conover drove an ambulance in France. Trained as a fighter pilot and was a decorated combat veteran.

In 2004, Church published her book “Diary of a WWI Pilot: Ambulances, Planes, Friends.”

“I wouldn’t have been able to write the book without the diaries,” she said.

So here we are in 2011, and people are writing diary-style entries everywhere in cyberspace. On Facebook (800 million users), on Twitter (100 million users) and in emails (294 billion emails sent per day).

Bodes well for family members 50 years hence who hope to weave together a family history, based on diary-style entries, right?

Probably wrong.

No one can say for certain how long Facebook posts and tweets will stay in cyberspace. And who can still locate that 2002 email describing the enchanting family vacation?

“Part of the problem is that we are so overwhelmed with email in any given day that it’s difficult to process their historical significance,” Soden explained.

“And you are encouraged, for sustainability reasons, not to print out a bunch of email. That makes preservation of these communications more and more difficult.”

Sarah Conover teaches creative writing in the seniors program at the Community Colleges’ Institute for Extended Learning.

Her students often work on their memoirs, drawing forth details from letters written by their parents a century ago.

Conover was a toddler when her parents died, so she has no memories of them. But she treasures the letters her father wrote to friends and family in the 1950s.

“I wouldn’t have a sense of his personality if I didn’t have them,” she said.

People once wrote so many letters that in 1954 the postmaster general panicked in his annual report. Post offices, he wrote, were being taken over by the mail.

Now, excluding birthday and holiday letters, Americans on average receive one personal letter every seven weeks, according to the Associated Press. Just this past week, the U.S. Postal Service announced budget cuts and consolidations because people aren’t sending as much mail as they used to.

Historians value letters for their candor.

“In letters, privacy is important,” Soden said. “But anytime you think this is going to be read by someone else, in addition to the person you are writing to, you are going to say it differently.”

Conover also possesses almost a dozen newspaper and magazine articles about the 1958 boating tragedy.

“It was considered one of the biggest sailing incidents up to that point,” she said.

Sports Illustrated wrote a lengthy article about the ship’s disappearance during the worst storm ever recorded in the history of Miami’s weather bureau. Several boating magazines wrote about it, too, as did newspapers throughout the country.

Newspapers are sometimes called “history in a hurry.” So what happens as newspapers shrink or die?

Last week, the Reynolds Journalism Institute released a report about the future of newspaper preservation. Newspaper archivists were among the first let go in the past decade of newspaper downsizing, the report pointed out, and newspaper microfilm donated to historical societies and libraries is sometimes inaccessible due to budget cuts at those institutions.

In May, Google abandoned its ambitious five-year project to digitize the country’s newspaper archives, including archives from The Spokesman-Review.

And with fewer newspaper reporters – more than 15,000 newspaper jobs were eliminated in 2009 alone, according to News Cycle, an industry watchdog – not as many people are writing history in a hurry anymore, anyway.

“There are backfiles in strange formats on obsolete media at every newspaper that are either lost or on their way there,” the Reynolds Journalism Institute reported.

“There may be web pages ‘somewhere’ on a newspaper’s server, but once the newspaper stops linking to them from active pages there is no way to access them.”

Don’t be crying into your great-grandma’s letters just yet.

Peter Boag, history professor at Washington State University, isn’t worried about losing traditional sources of history, such as letters and newspapers.

To write his history books, Boag relies on legal records and census data.

“I’m pretty sure those types of records will still be kept,” he said.

And he finds digital sources – the newspaper archives Google scanned before abandoning the project, for instance – invaluable.

“I finished my Ph.D. in 1988,” he said. “The Internet was just in its infancy. Now, one can do all sorts of research sitting in their office.”

Boag trusts the ingenuity of historians, present and future.

“Historians are incredibly clever about changing the way they do research as the sources change,” he said. “In the 19th century, they couldn’t imagine what we have today.”

Historians also study “material culture” – items made by humans that play important roles in their culture, such as coins.

Conover doesn’t possess much primary material about her mother, who was in her mid-20s when lost at sea, but Conover treasures one material-culture item.

“Her recipe book,” Conover said, clutching the wooden box to her heart. “The recipes are in her handwriting.”