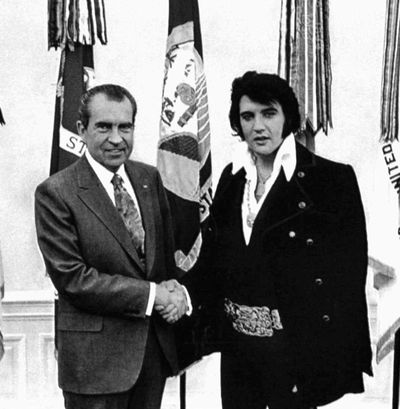

When Elvis met Nixon

Eyewitnesses recall story behind photo

WASHINGTON – The National Archives is like a safe deposit box for America’s really important papers – the Bill of Rights, the Declaration of Independence, the $7.2 million canceled check for the purchase of Alaska, the picture of Richard Nixon and Elvis Presley shaking hands in the Oval Office.

Copies of that photo – the president in his charcoal suit, the King of Rock ’n’ Roll in his purple velvet cape – are requested more than just about any of the archives’ treasures, including the Constitution.

Yet the story that led to their improbable meeting on Dec. 21, 1970, is as little known as the picture is famous. In honor of Elvis’ 75th birthday, one of the president’s men, Egil “Bud” Krogh, and one of the king’s most trusted friends, Jerry Schilling, met for the first time in almost 40 years at the National Archives to recount the day Elvis came to Washington. A crowd waited in the frigid cold for a seat. (Even in the imperious capital, Elvis can still pack a house.)

It wasn’t the glitzy birthday party other cities threw, no giant birthday card signings, all-night film festivals or ogling the white jumpsuit called “Snowflake.” An Elvis exhibit at the National Portrait Gallery is more Washington’s speed. As was this forum, which offered an hourlong window into a simpler time, before Watergate or terror attacks, when the world’s most famous man asked the world’s most powerful one to grant him a wish, and got it.

Elvis on the move

The story begins Dec. 19, 1970, at Schilling’s home in the Hollywood Hills. The phone rings. A voice says, “It’s me.”

Elvis is at the Dallas airport on his way to Los Angeles and wants Schilling to pick him up at LAX.

“Who’s with you?” Schilling asks.

“Nobody,” the king says.

It should be noted that Elvis was a man who almost never did anything alone. He wanted at least five guys around him just to sit and watch TV. So Schilling is understandably concerned, all the more so when Elvis proceeds to recite his flight number and arrival time, which is akin to the queen doing her own laundry.

Schilling races to the airport and takes Elvis back to his home. The next morning, it comes out that Vernon, Elvis’ father, and Priscilla, his wife, were bugging him about how he spent his money. This aggravated the king so, all by himself, he got on the first plane going out, which happened to be bound for Washington.

Things did not go well.

For starters, a “smart aleck little steward” discovers Elvis is carrying a gun – it was his habit, we learn, to carry at least three – and informs him he cannot bring a firearm on the airplane. Elvis, unaccustomed to being told what to do, storms off, and is chased down by the pilot: “I’m sorry, Mr. Presley, of course you can keep your gun.” Elvis and his firearm re-board.

At some point, Elvis has enough of this traveling alone stuff and heads to Los Angeles, intent on returning with one of his Memphis Mafia, namely Schilling.

Schilling, who first met Elvis when he was 12, is accustomed to odd requests from the king. But this one is particularly weird because Elvis is bent on going to Washington and won’t say why. Still, because “you don’t say no to Elvis,” Schilling agrees to go.

Headed for D.C.

They book two first-class seats to D.C., but still need cash, and it’s a Sunday night in 1970. No ATMs. Elvis’ limousine driver, Sir Gerald, arranges for a check to be cashed at the Beverly Hilton Hotel. Schilling writes one for $500, which Elvis signs. Before they leave Schilling’s house, Elvis, a history buff, takes a commemorative World War II Colt .45-caliber revolver off the wall, bullets included, and stows it in his bag.

On the plane, Elvis bumps into George Murphy, a song-and-dance man turned U.S. senator from California. They chat for a while, and Elvis comes back to his seat asking for stationery, which a stewardess gets him. Elvis, who has only written three letters in his life, all while stationed with the Army in Germany, sits down to write the fourth one to the president of the United States.

“Dear Mr. President, First I would like to introduce myself. I am Elvis Presley.”

In five pages, Elvis explains he loves his country and wants to give something back and, not being “a member of the Establishment,” believes he could reach some people the president can’t if the president would only make him a federal agent-at-large so he can help fight the war on drugs.

“Sir, I can and will be of any service that I can to help the country out. … I will be here for as long as it takes to get the credentials of a federal agent. … I would love to meet you just to say hello if you’re not to (sic) busy. Respectfully, Elvis Presley.”

He asks the president to give him a call at the Washington Hotel, Room 505, where he will be staying under the alias Jon Burrows (a part he played in one of his movies). He provides six private numbers that any one of his fans would have killed for.

At the White House

The plane lands before dawn and they get in a limo Sir Gerald arranged before they left. Elvis wants to personally deliver the letter to the White House. “I don’t think this is such a good idea,” Schilling says, noting the hour.

Next scene: The limo pulls up to the northwest gate. Elvis gets out, and hands his letter to a security guard, who sizes up this guy in a cape. Schilling, realizing that in the dark Elvis looks a lot like Dracula, jumps out and explains. The guard agrees to deliver the letter to the president. Elvis and Schilling retire to the Washington Hotel to wait.

Early that morning, the letter finds its way to the desk of Dwight Chapin, special assistant to the president. After a moment of head-scratching, he decides this meeting has to take place. Nixon had already tried to enlist Hollywood’s help fighting the war on drugs by approaching such luminaries as Art Linkletter; Elvis is a definite step up.

So Chapin fires off a memo to Krogh, which Krogh dismisses as a practical joke. Deciding to play along, he calls the hotel, asks for Schilling and is impressed that Chapin has found someone to impersonate an Elvis lackey.

The more they talk, however, the more Krogh realizes this is no joke. He shoots a memo to White House chief of staff H.R. Haldeman, suggesting this could be a real boost for the drug war effort, which isn’t going so well.

“You must be kidding,” Haldeman scribbles in the margin before approving the request. The meeting is on.

White House schedulers find five minutes at 11:45 a.m. for Elvis, who, on time for once, enters wearing tight purple velvet pants, the matching cape, a white pointy collared shirt unbuttoned to reveal two enormous gold chains.

The meeting

At 12:30, the president meets the king. Elvis is taken by the eagles on the ceiling, and Krogh has to give him a little steer toward Nixon.

Soon, though, Elvis is pulling out pictures of his wife and baby, along with photos of assorted police and security badges he has collected over the years. The allotted five minutes pass, and they’re still going, bonding over their lowly beginnings (poverty, challenging childhoods). They commiserate about the burdens of fame, what a hard gig Vegas is (which, weirdly, Nixon seems to know about). Elvis offers to help Nixon fight the war on drugs and restore respect for the flag. Nixon admires Elvis’ big cuff links.

Then Elvis asks for what he’s been after all along, a big gold badge to add to his collection, the thing that would make him a federal agent-at-large for the Bureau of Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs. He had tried to get one from an agency head and was turned down, which is why he decided to go straight to Nixon.

“Can I be one?” Elvis asks his new friend.

“Well, federal agents-at-large – we just don’t have those,” Nixon stammers.

“I’ll look into it,” Krogh promises.

Elvis is crestfallen, visibly wilted under the weight of all that gold, a man who could have anything – cars, women, houses – except the one thing he wants most.

Nixon takes one look at him and caves.

“Get him the badge.”

Elvis is so excited he gives the president a big hug.

Then it’s time for gifts. Elvis pulls out the commemorative Colt 45 he had taken from his wall and carried into the White House, to the dismay of the Secret Service. He presents it to Nixon.

The president moves over to a big drawer of presents he keeps on the left side of his desk, its contents organized in order of increasing value: golf balls in front, pens, paperweights, and way in the back, 16-karat gold pendants, lapel pins and brooches. Nixon peruses the drawer with Elvis peeking over his shoulder. He pulls out gifts for Schilling and another friend.

“You know, Mr. President, they have wives,” Elvis says. Nixon goes back for more. Elvis motions to the 16-karat stuff. (Schilling’s wife still has her brooch.)

The two men agree their meeting is best kept a secret. Nixon is sinking in the polls, Elvis is working on his comeback, and neither of their constituencies was likely to understand. The Leader of the Free World and the King of Rock ’n’ Roll say their goodbyes.

For 13 months, the secret was safe. Not a security guard or a staffer, not any of the men with whom Elvis shook hands or the women he kissed when aides took him down to the White House mess for lunch afterward, breathed a word.

The aftermath

It wasn’t until columnist Jack Anderson got hold of the galleys of a memoir by Deputy Narcotics Director John Finlator that the news broke: “Elvis Presley, the swivel-hipped singer, has been issued a federal narcotics badge.”

Epilogue: Nixon resigned from office under threat of impeachment 3 1/2 years later, on Aug. 9, 1974. When he was subsequently hospitalized with phlebitis, Elvis called to wish him well.

Elvis died at age 42 on Aug. 16, 1977, of a heart attack; 14 prescription drugs were found in his system. Nixon later noted in his friend’s defense that those were not illegal drugs.

The commemorative gun is on display at the Nixon Library in Yorba Linda, Calif.

The badge, specially prepared by the Bureau of Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs with Elvis’ name on it, now hangs in his home in Graceland, on the Wall of Gold.