Farmington State Bank thrives by sticking to its rural roots

John Widman is the president of Farmington State Bank in downtown Farmington, Wash. (Dan Pelle)

FARMINGTON, Wash. – Farmington State Bank is strictly no-frills.

The bank does not offer a credit card. Customers cannot access their accounts over the Internet.

A few years ago it stopped making mortgage loans because the paperwork became too onerous, President John Widman said.

The bank has remained in the same building on the southwest corner of Main and First streets since 1911, when the then-14-year-old institution moved out of offices over a saloon.

Copper safe deposit boxes honeycomb a section of the concrete vault. In the middle squats the “widow-maker,” a circular safe so heavy it might as well have been drop-forged in place.

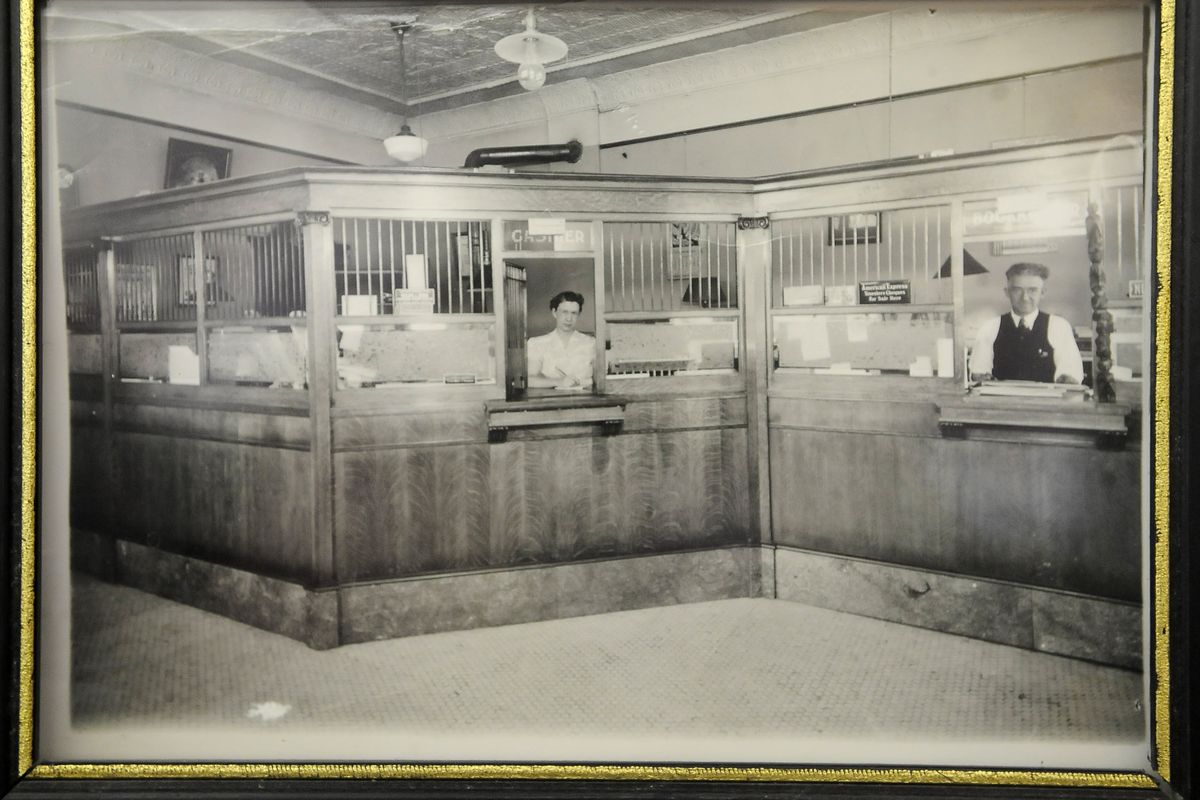

There are photos of the original bank building on the lobby wall, along with a photocopy of an $800 check written in 1889.

“That was a lot of money in those days,” Widman said.

Also on the wall is a statement of the bank’s condition, a document few financial institutions put anywhere customers can readily see.

But Farmington State Bank has nothing to hide. As of Sept. 30, the bank was unique among Washington’s 82 FDIC-insured banks: There were no bad loans on the books.

While other, far bigger banks expanded and loaned themselves into oblivion, Farmington stayed home, Widman said.

Although its $6.6 million in deposits considerably outweigh the $5.7 million in loans on its books, he said the bank has never been tempted to look far beyond its hometown and the farmers – some third- and fourth-generation – who for decades have turned to it for operating capital.

“We deal in a select service area,” Widman said.

Farmington sits in Whitman County, a few miles south of Spokane County and a few hundred yards from the Idaho border.

Agricultural loans constitute about three-quarters of the bank’s loan portfolio, and high prices for farm commodities in recent years have enabled farm borrowers to repay their loans when the harvest comes in, Widman said.

The few loan requests he rejects are made by newcomers, or applicants who have already been passed over by other banks.

He said Farmington sets aside all of $300 per month to allow for potential loan losses.

“We have had reverses,” Widman said. “But we’ve been able to get out of them with a minimal loss.”

Ultra-conservative management has yielded an ultra-envious balance sheet. Farmington’s capital ratio – equity to assets – is 25 percent, 250 percent of the regulatory minimum.

Brad Williamson, Division of Banking director for the Washington Department of Financial Institutions, said Farmington must meet the same regulatory standards as much larger banks. But as a small bank that sticks to its knitting, the level of concern is low, he said.

“They’re not very high on our radar screen in terms of risk,” Williamson said.

Low-profile and low-key works for Widman, an area native who describes himself as a hobby farmer.

In a now-tiny town of 160, down from more than 2,000 early in the 20th century, the Farmington Bank lobby is the only place in town where coffee is always on, made by Widman or one of the bank’s two tellers, Linda Wagner and Tanya Thygeson. Customers have pulled up in combines, or with a new calf they want to show off, he said.

“You pick up the phone, and you recognize the voice,” Wagner said.

One of those voices could be that of Archie Chan, a British citizen who lives in Hong Kong.

Widman said Chan bought the bank in 1995, when he was looking for a chartered Washington bank that might become a platform for international banking. That did not happen, but Widman said Chan has passed on offers for Farmington, settling instead for the modest earnings – $63,000 in the third quarter – the bank generates.

Another owner would probably move it, Widman said.

“We think we’re probably one of the smallest banks west of the Mississippi River,” he said.

“It’s a little niche that you don’t see very often.”