King Cole, “Father of Expo ‘74,” dies

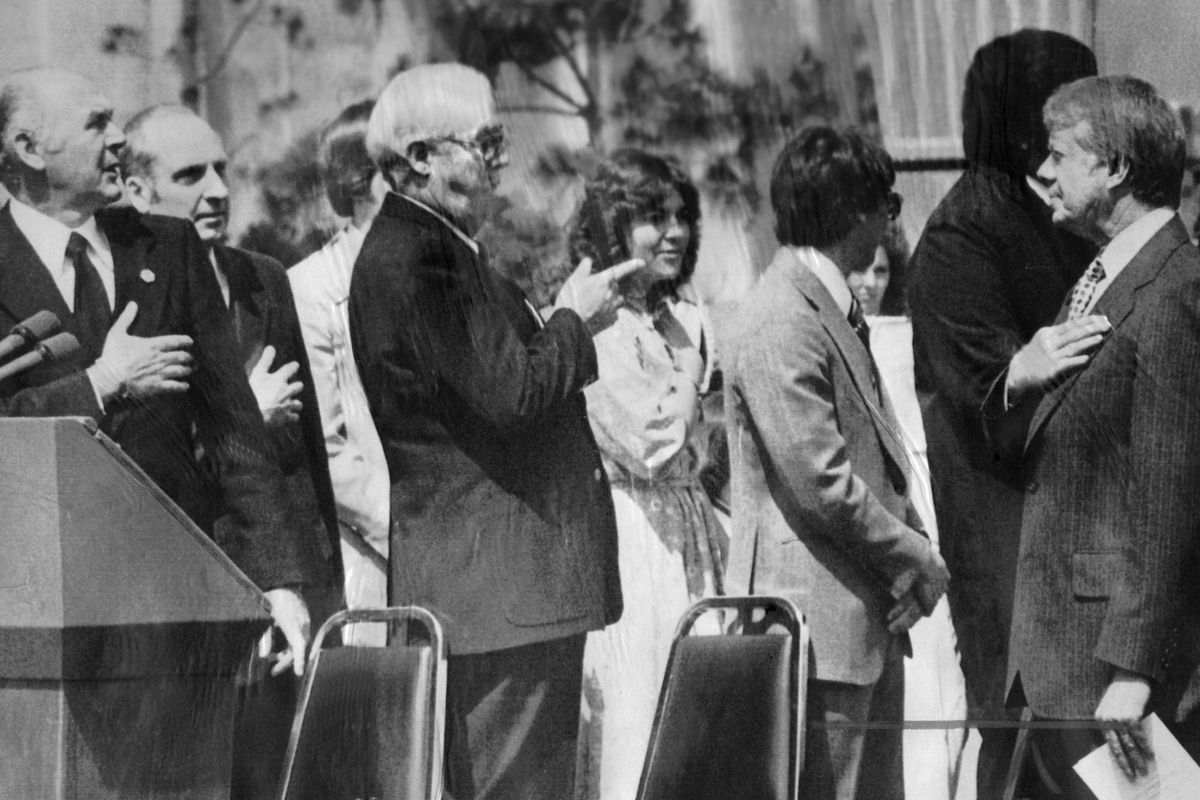

King Cole, President of Expo '74, left, is given a piece of cake designed to celebrate the pre-birthday of Expo 74 in Spokane. Chef John Wolfsheimen and Congressman Tom Foley are also in this 1973 photo. (Spokesman-Review Archive Photo)

King Cole, the “father” of Expo ’74, who believed long before most everyone else that Spokane was big enough to host a world’s fair, died Sunday. He was 88.

“King Cole was a primary force in the conception and staging of Expo ’74 and the resulting resurrection of our central business district,” said David Rodgers, who was mayor of Spokane during Expo.

“He was truly one of Spokane’s most effective leaders of the last century.”

During its six month-run, from May to November 1974, more than 5 million people visited Expo ’74. The world’s fair site is now Riverfront Park.

For newcomers to Spokane, or those too young to remember what Spokane was like before Expo ’74, Mike Kobluk, who was director of performing and visual arts at Expo, put Cole’s efforts in perspective:

“Just a few days ago, I watched ‘It’s a Wonderful Life.’ In the movie, George Bailey finds out what the city was like without him. Without King Cole and the people who worked with him, we’d still have two levels of railroad going down Trent Avenue. It wouldn’t even be called Spokane Falls Boulevard.

“We would not have an opera house,” Kobluk pointed out. “We would not have a Riverfront Park. This city would be nothing like it is. He revitalized a downtown through a world’s fair.”

Cole was born Feb. 10, 1922 in Grand Junction, Colo.

“I never thought the name King Cole shaped my destiny until I looked back,” Cole said in a 2008 interview with The Spokesman-Review. “My dad predicted it. He said: ‘This will open a lot of doors for you when you grow up.’ And in a strange, comic book sort of way, it did.”

In 1963, Cole, community development director in San Leandro, Calif., was hired by the business group, Spokane Unlimited, to help jumpstart Spokane’s lagging economy.

Railroad yards obscured the Spokane River Falls that flowed through downtown. Cole and his wife, Jan — and their eight children — settled in, and Cole got to work shaping a new image for Spokane.

“Shortly after I arrived in November 1963, I was standing in line at the old Payless drugstore downtown waiting to pay at the cash register,” he recalled in 2008.

“Some customer had just handed back to the clerk the phone book he borrowed. The clerk looked at us all in line and said, ‘Look at this phone book. People are leaving this town in droves. This phone book used to be a growing thing.’

“I said in front of everybody, ‘Where’s your proof that people are leaving your town in droves? I just got here. I came because people are not leaving. God knows they’ve got a good enough case for thinking they should. But they’re sticking it out. That’s what is going to save this town. Why aren’t you on that side?’”

Plans for the urban renewal of Spokane, in the guise of a world’s fair, began in earnest in the late 1960s.

Cole traveled 700,000 miles in three years, garnering support from local, state and national leaders and the Bureau of International Expositions.

He also helped broker the deal between the city and railroad officials who agreed to a land swap for most of the needed property on the Spokane River downtown.

“I was gone more than I was home,” Cole remembered of those years leading up to Expo. “Even though it was tough on Jan, I was feeling jealous of my wife because she had the children all the time.”

His favorite memory of Expo ’74 happened before it even opened.

Cole, whose official title was president of Expo ’74, remembered: “I had to go under train trestles to get to my office at the Paulsen Building. I went under the first trestle and under the second trestle and one morning the third trestle, the one on the fair site, was gone.

“And there was Mount Spokane. I had an epiphany. If everything stopped dead at that point and nothing else were to happen as far as the fair was concerned, the objective of the world’s fair was met. The mess was cleaned up.”

Expo ’74 opened May 4, 1974, to a crowd of 85,000. Speakers included President Richard Nixon, Gov. Dan Evans and Congressman Tom Foley. The event pumped an estimated $150 million into the local economy and surrounding region. Cole, who had studied for the priesthood in a Catholic seminary for seven years before deciding against that vocation, said the training came in handy once Expo was in full swing.

“I took seven years of Latin,” he said. “Many of the languages of the countries that came to Expo were easy for me to grasp, because they were Latin-based.”

After the world’s fair closed, Cole opened a consulting business, King Cole of Spokane Inc., and later served as the executive consultant for the Knoxville International Exposition in 1982. Until that year, Spokane was the smallest city to host a world’s fair.

In his later years, he suffered with chronic pain and numbness from peripheral neuropathy, but he always said yes to interview requests from historians and journalists.

His wife Jan was his devoted caregiver for years. In 2008, when Cole was asked the secret to his success, he looked at his wife and said, “She’s sitting across from me.”

Two years ago, Cole broke a hip and depended on a wheelchair to get around.

His daughter, Lisa Taylor, said he loved when his grown children drove him through downtown Spokane in these last years.

“He would just get giddy weaving through the streets,” Taylor said. “He told stories. He’d see something new and see activities and people. Downtown was the heart and to see it healthy was his greatest pleasure.”

Cole is survived by wife, Jan, eight children, 17 grandchildren and eight great-grandchildren.

“He was going to be a great-great grandfather in May, and he was waiting for that, because it was going to be five generations of Coles,” said daughter Mary Cole.

“Above everything else, his family was the most important to him.”

Vigil services will be Wednesday at 7 p.m. at Our Lady of Fatima Catholic Church, 1517 E. 33rd Ave., with a funeral Mass Thursday at 10 a.m., also at the church.

“Spokane has lost a legend,” said Lois Stratton, a former Washington state legislator who served as Cole’s secretary during Expo. “King Cole gave his heart and soul to Spokane.”