Great Burn Wilderness remains subject of debate

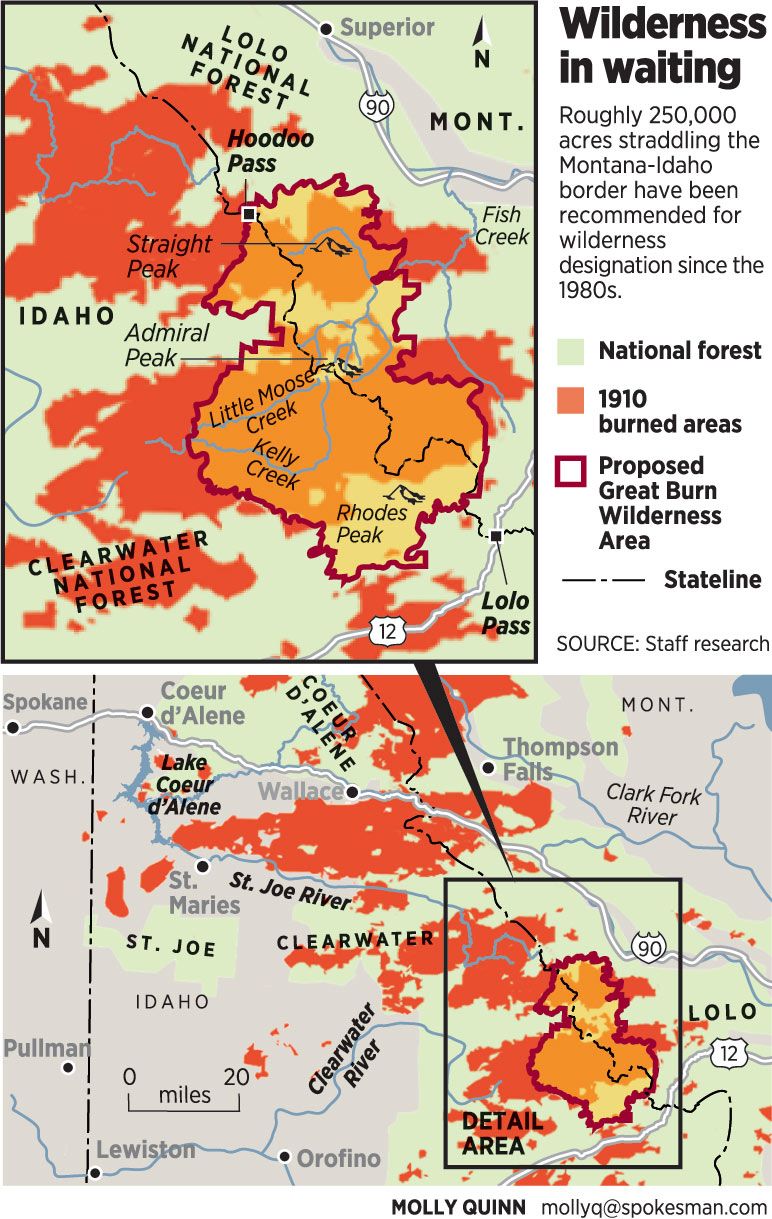

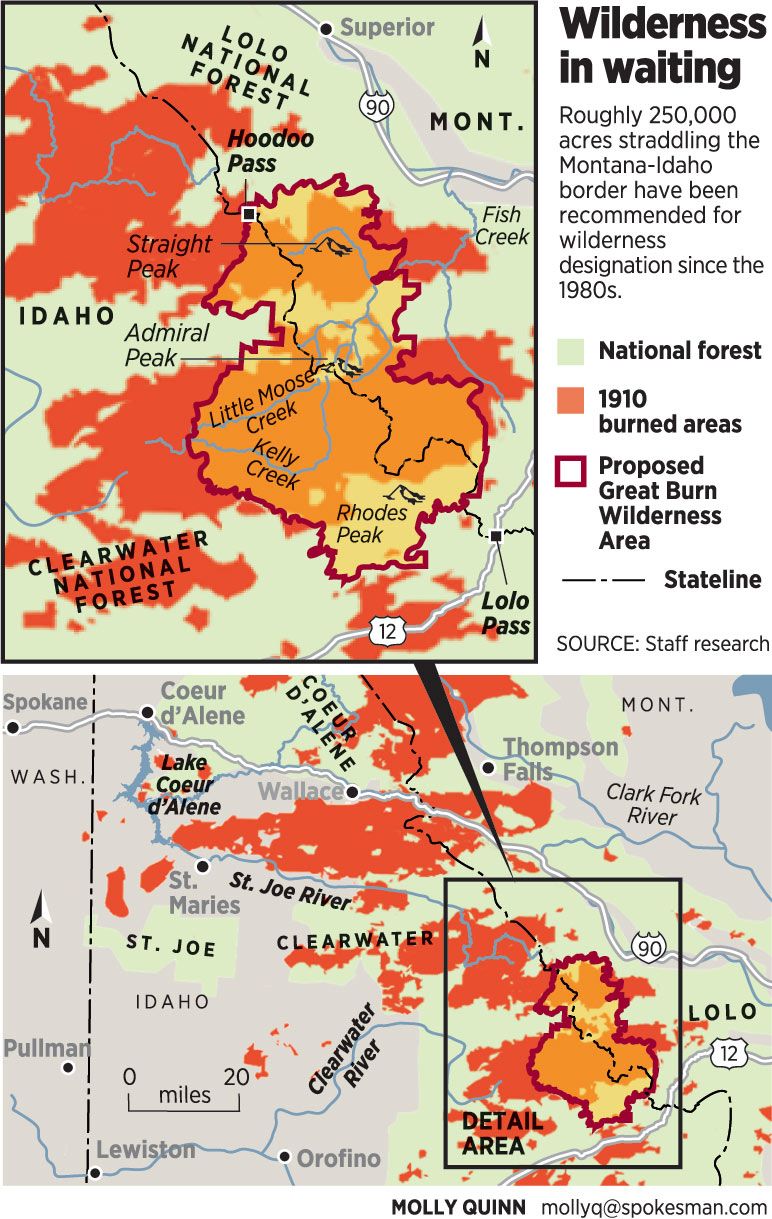

275,000 acres proposed for protection along Bitterroot Divide

The 1910 fires – and significant wildfires that followed into the 1930s – had a devastating hand in bestowing rugged portions of the Bitterroot Mountains with new life.

The landscape was so thoroughly blackened in some areas between Lookout and Lolo passes, loggers turned their attention elsewhere while nature found a new canvas for blending its palette of flora and fauna.

Fires had essentially banked a reservoir of wildness eventually recognized by national forest managers.

And as the land has gradually been rediscovered by recreationists, a decades-old debate still smolders over proposals to designate roughly 275,000 acres along the Bitterroot Divide and Montana-Idaho border as the Great Burn Wilderness.

The name Great Burn stems from the epic August 1910 “blowup” as hundreds of lightning- and human-caused blazes exploded into an inferno whipped by hurricane-force winds.

When it was over two days later, much of a 3-million-acre path 260 miles long and 200 miles wide from the Salmon River north to Canada was charred.

Most of the destruction occurred in just six hours.

“The Great Burn area that’s proposed for wilderness is a unique ecosystem in a lot of different ways,” said Orville Daniels of Missoula, a fire ecologist and supervisor of the Bitterroot or Lolo national forests from 1970 until he retired in 1994.

“The landforms and geology are different than the rest of the region; so is the ecology. There’s a different moisture regime. We call it the weepy, seepy.”

More than 30 lakes dot both sides of the Bitterroot Divide in the area proposed for wilderness from Hoodoo Pass south nearly to Lolo Pass.

Roadless headwaters and cold, clear waters have made Idaho’s Kelly Creek a world-class native cutthroat stream and Montana’s Fish Creek the most important habitat for threatened bull trout in the middle Clark Fork drainage.

The Great Burn’s diversity is spiced by pockets of timber leap-frogged by the fires, such as those up the West Fork of Fish Creek where 550-year-old Western red cedars still stand.

But it’s the fires that set the area apart in our lifetime, Daniels said.

“They opened the country.”

Still, the notion to preserve and protect the transformed landscape for future generations was decades off.

While much of the area was of no immediate interest to loggers, livestock grazers had their eye on greenery emerging from newly opened spaces.

“In the 1920s out of Superior, they shipped 100,000 head of domestic sheep that had summered in the Great Burn,” Daniels said. “That, of course, had an impact on the ecosystem, too.”

The land has continued to mature, and Daniels guessed that 5,000 sheep couldn’t make a living there now.

But a wilder sort of grazing followed as brush displaced the domestics.

As the path of the fires gradually developed into vast meadows of grasses, forbs and taller brush, the landscape became ripe for lynx, wolverines, mountain goats, and especially for Rocky Mountain elk, which had largely been extirpated by early settlers.

Elk from Yellowstone Park were delivered by truck and train in the 1930s to jumpstart herds in the Bitterroot and Clearwater regions. In a refuge of rugged terrain and few roads, the elk flourished in their rich new habitat – even in the Lolo and Lochsa areas where the Lewis and Clark Expedition nearly starved for lack of game in the region’s paltry wildlife habitat.

“By the ‘50s,” Daniels said, “the Great Burn area had the premier elk herd in the United States,” a distinction that wasn’t overlooked by popular hunting writers, such as Jack O’Connor.

“It stands out in my mind that the staff on the Superior District was proposing the Great Burn for wilderness in 1968, just four years after the Wilderness Act. That land, also called the Hoodoo roadless area, had struck those folks as such special country even at a time when the Forest Service mission was so strongly for timber.”

When the Lolo National Forest was writing management plans in the 1970s, foresters projected it would be two more decades before timber regenerating in their portion of the Great Burn would be mature for logging.

Directed by Congress, all the forests were required to evaluate roadless acres in the ‘70s and ‘80s and recommend areas to be considered for designation as wilderness, the most protective status for public land.

The Great Burn emerged strong. Even though the timber and mining industries had dug in their heels to counter the national wilderness movement, the Great Burn generally had their support because it was rugged, remote from mills and still relatively timber-poor, said Doug Gober, North Fork District Ranger in Orofino.

In the mid ‘80s, National Geographic searched North America and selected eight unique ecosystems to feature in a book, “America’s Hidden Wilderness: Lands of Seclusion.”

The Great Burn roadless area was among the chosen few, along with Utah’s Grand Gulch, the Mojave Desert and the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge.

Dale Harris, 63, of Missoula, formerly with the Wilderness Institute at the University of Montana, helped guide a National Geographic photographer through the Great Burn over six weeks.

“The burn is not spectacular for being vertical, like Glacier Park, but rather for its horizontal landscape and connectivity for wildlife,” Harris said. “The photographer had no trouble finding material. He shot 10,000 photos.”

The book was published in 1988, just before a Montana wilderness bill championed by Sen. John Melcher, D-Mont., passed Congress only to be pocket-vetoed by President Ronald Reagan in a move that helped Republican Conrad Burns unseat Melcher in the next election.

The Great Burn continues to be a victim of the stalemate the “W” word has caused between conservationists and industry in Montana and Idaho.

Current Montana Sen. Jon Tester has introduced the Forest Jobs and Recreation Act, a bill seeking to end this drawn-out dispute over wilderness in Western Montana. It does not include the Great Burn, partly to avoid political complications with its extension into Idaho.

Tester’s is the first wilderness bill introduced by the Montana delegation since 1997 – and it’s noteworthy that the bill does not include the term “wilderness.”

But there’s new hope for the Great Burn’s Wilderness-in-waiting through a group convened two years ago by Sen. Mike Crapo, R-Idaho,

The Clearwater Basin Collaborative won a national pat on the back this month for bringing conservation, recreation, industry and community groups together on public land issues, earning a $1 million federal grant to improve watershed habitat.

The CBC is on a roll, and the Great Burn is high on its agenda, said Harris, whose 40 years of wilderness advocacy was tapped with a seat at the CBC table.

“The industry is supporting a conservation agenda in areas including the Great Burn in return for consideration of land were looking at for management activity in other portions of the national forest,” said Bill Higgins of Grangeville, spokesman for the Idaho Forest Group and CBC member.

Higgins is reasonably confident that about 102 years after the 1910 fires distinguished the Great Burn, there’s likely to be a wilderness bill supported by industry and conservationists, snowmobilers and skiers – an outcome almost as epic as the Big Burn itself.

The Great Burn’s diversity is spiced by pockets of timber leap-frogged by the fires, such as those up the West Fork of Fish Creek where 550-year-old Western red cedars still stand.

But it’s the fires that set the area apart in our lifetime, Daniels said.

“They opened the country.”

Still, the notion to preserve and protect the transformed landscape for future generations was decades off.

While much of the area was of no immediate interest to loggers, livestock grazers had their eye on greenery emerging from newly opened spaces.

“In the 1920s out of Superior, they shipped 100,000 head of domestic sheep that had summered in the Great Burn,” Daniels said. “That, of course, had an impact on the ecosystem, too.”

The land has continued to mature, and Daniels guessed that 5,000 sheep couldn’t make a living there now.

But a wilder sort of grazing followed as brush displaced the domestics.

As the path of the fires gradually developed into vast meadows of grasses, forbs and taller brush, the landscape became ripe for lynx, wolverines, mountain goats, and especially for Rocky Mountain elk, which had largely been extirpated by early settlers.

Elk from Yellowstone Park were delivered by truck and train in the 1930s to jumpstart herds in the Bitterroot and Clearwater regions. In a refuge of rugged terrain and few roads, the elk flourished in their rich new habitat – even in the Lolo and Lochsa areas where the Lewis and Clark Expedition nearly starved for lack of game in the region’s paltry wildlife habitat.

“By the ‘50s,” Daniels said, “the Great Burn area had the premier elk herd in the United States,” a distinction that wasn’t overlooked by popular hunting writers, such as Jack O’Connor.

“It stands out in my mind that the staff on the Superior District was proposing the Great Burn for wilderness in 1968, just four years after the Wilderness Act. That land, also called the Hoodoo roadless area, had struck those folks as such special country even at a time when the Forest Service mission was so strongly for timber.”

When the Lolo National Forest was writing management plans in the 1970s, foresters projected it would be two more decades before timber regenerating in their portion of the Great Burn would be mature for logging.

Directed by Congress, all the forests were required to evaluate roadless acres in the ‘70s and ‘80s and recommend areas to be considered for designation as wilderness, the most protective status for public land.

The Great Burn emerged strong. Even though the timber and mining industries had dug in their heels to counter the national wilderness movement, the Great Burn generally had their support because it was rugged, remote from mills and still relatively timber-poor, said Doug Gober, North Fork District Ranger in Orofino.

In the mid ‘80s, National Geographic searched North America and selected eight unique ecosystems to feature in a book, “America’s Hidden Wilderness: Lands of Seclusion.”

The Great Burn roadless area was among the chosen few, along with Utah’s Grand Gulch, the Mojave Desert and the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge.

Dale Harris, 63, of Missoula, formerly with the Wilderness Institute at the University of Montana, helped guide a National Geographic photographer through the Great Burn over six weeks.

“The burn is not spectacular for being vertical, like Glacier Park, but rather for its horizontal landscape and connectivity for wildlife,” Harris said. “The photographer had no trouble finding material. He shot 10,000 photos.”

The book was published in 1988, just before a Montana wilderness bill championed by Sen. John Melcher, D-Mont., passed Congress only to be pocket-vetoed by President Ronald Reagan in a move that helped Republican Conrad Burns unseat Melcher in the next election.

The Great Burn continues to be a victim of the stalemate the “W” word has caused between conservationists and industry in Montana and Idaho.

Current Montana Sen. Jon Tester has introduced the Forest Jobs and Recreation Act, a bill seeking to end this drawn-out dispute over wilderness in Western Montana. It does not include the Great Burn, partly to avoid political complications with its extension into Idaho.

Tester’s is the first wilderness bill introduced by the Montana delegation since 1997 – and it’s noteworthy that the bill does not include the term “wilderness.”

But there’s new hope for the Great Burn’s Wilderness-in-waiting through a group convened two years ago by Sen. Mike Crapo, R-Idaho,

The Clearwater Basin Collaborative won a national pat on the back this month for bringing conservation, recreation, industry and community groups together on public land issues, earning a $1 million federal grant to improve watershed habitat.

The CBC is on a roll, and the Great Burn is high on its agenda, said Harris, whose 40 years of wilderness advocacy was tapped with a seat at the CBC table.

“The industry is supporting a conservation agenda in areas including the Great Burn in return for consideration of land were looking at for management activity in other portions of the national forest,” said Bill Higgins of Grangeville, spokesman for the Idaho Forest Group and CBC member.

Higgins is reasonably confident that about 102 years after the 1910 fires distinguished the Great Burn, there’s likely to be a wilderness bill supported by industry and conservationists, snowmobilers and skiers – an outcome almost as epic as the Big Burn itself.

The Great Burn’s diversity is spiced by pockets of timber leap-frogged by the fires, such as those up the West Fork of Fish Creek where 550-year-old Western red cedars still stand.

But it’s the fires that set the area apart in our lifetime, Daniels said.

“They opened the country.”

Still, the notion to preserve and protect the transformed landscape for future generations was decades off.

While much of the area was of no immediate interest to loggers, livestock grazers had their eye on greenery emerging from newly opened spaces.

“In the 1920s out of Superior, they shipped 100,000 head of domestic sheep that had summered in the Great Burn,” Daniels said. “That, of course, had an impact on the ecosystem, too.”

The land has continued to mature, and Daniels guessed that 5,000 sheep couldn’t make a living there now.

But a wilder sort of grazing followed as brush displaced the domestics.

As the path of the fires gradually developed into vast meadows of grasses, forbs and taller brush, the landscape became ripe for lynx, wolverines, mountain goats, and especially for Rocky Mountain elk, which had largely been extirpated by early settlers.

Elk from Yellowstone Park were delivered by truck and train in the 1930s to jumpstart herds in the Bitterroot and Clearwater regions. In a refuge of rugged terrain and few roads, the elk flourished in their rich new habitat – even in the Lolo and Lochsa areas where the Lewis and Clark Expedition nearly starved for lack of game in the region’s paltry wildlife habitat.

“By the ‘50s,” Daniels said, “the Great Burn area had the premier elk herd in the United States,” a distinction that wasn’t overlooked by popular hunting writers, such as Jack O’Connor.

“It stands out in my mind that the staff on the Superior District was proposing the Great Burn for wilderness in 1968, just four years after the Wilderness Act. That land, also called the Hoodoo roadless area, had struck those folks as such special country even at a time when the Forest Service mission was so strongly for timber.”

When the Lolo National Forest was writing management plans in the 1970s, foresters projected it would be two more decades before timber regenerating in their portion of the Great Burn would be mature for logging.

Directed by Congress, all the forests were required to evaluate roadless acres in the ‘70s and ‘80s and recommend areas to be considered for designation as wilderness, the most protective status for public land.

The Great Burn emerged strong. Even though the timber and mining industries had dug in their heels to counter the national wilderness movement, the Great Burn generally had their support because it was rugged, remote from mills and still relatively timber-poor, said Doug Gober, North Fork District Ranger in Orofino.

In the mid ‘80s, National Geographic searched North America and selected eight unique ecosystems to feature in a book, “America’s Hidden Wilderness: Lands of Seclusion.”

The Great Burn roadless area was among the chosen few, along with Utah’s Grand Gulch, the Mojave Desert and the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge.

Dale Harris, 63, of Missoula, formerly with the Wilderness Institute at the University of Montana, helped guide a National Geographic photographer through the Great Burn over six weeks.

“The burn is not spectacular for being vertical, like Glacier Park, but rather for its horizontal landscape and connectivity for wildlife,” Harris said. “The photographer had no trouble finding material. He shot 10,000 photos.”

The book was published in 1988, just before a Montana wilderness bill championed by Sen. John Melcher, D-Mont., passed Congress only to be pocket-vetoed by President Ronald Reagan in a move that helped Republican Conrad Burns unseat Melcher in the next election.

The Great Burn continues to be a victim of the stalemate the “W” word has caused between conservationists and industry in Montana and Idaho.

Current Montana Sen. Jon Tester has introduced the Forest Jobs and Recreation Act, a bill seeking to end this drawn-out dispute over wilderness in Western Montana. It does not include the Great Burn, partly to avoid political complications with its extension into Idaho.

Tester’s is the first wilderness bill introduced by the Montana delegation since 1997 – and it’s noteworthy that the bill does not include the term “wilderness.”

But there’s new hope for the Great Burn’s Wilderness-in-waiting through a group convened two years ago by Sen. Mike Crapo, R-Idaho,

The Clearwater Basin Collaborative won a national pat on the back this month for bringing conservation, recreation, industry and community groups together on public land issues, earning a $1 million federal grant to improve watershed habitat.

The CBC is on a roll, and the Great Burn is high on its agenda, said Harris, whose 40 years of wilderness advocacy was tapped with a seat at the CBC table.

“The industry is supporting a conservation agenda in areas including the Great Burn in return for consideration of land were looking at for management activity in other portions of the national forest,” said Bill Higgins of Grangeville, spokesman for the Idaho Forest Group and CBC member.

Higgins is reasonably confident that about 102 years after the 1910 fires distinguished the Great Burn, there’s likely to be a wilderness bill supported by industry and conservationists, snowmobilers and skiers – an outcome almost as epic as the Big Burn itself.

The Great Burn’s diversity is spiced by pockets of timber leap-frogged by the fires, such as those up the West Fork of Fish Creek where 550-year-old Western red cedars still stand.

But it’s the fires that set the area apart in our lifetime, Daniels said.

“They opened the country.”

Still, the notion to preserve and protect the transformed landscape for future generations was decades off.

While much of the area was of no immediate interest to loggers, livestock grazers had their eye on greenery emerging from newly opened spaces.

“In the 1920s out of Superior, they shipped 100,000 head of domestic sheep that had summered in the Great Burn,” Daniels said. “That, of course, had an impact on the ecosystem, too.”

The land has continued to mature, and Daniels guessed that 5,000 sheep couldn’t make a living there now.

But a wilder sort of grazing followed as brush displaced the domestics.

As the path of the fires gradually developed into vast meadows of grasses, forbs and taller brush, the landscape became ripe for lynx, wolverines, mountain goats, and especially for Rocky Mountain elk, which had largely been extirpated by early settlers.

Elk from Yellowstone Park were delivered by truck and train in the 1930s to jumpstart herds in the Bitterroot and Clearwater regions. In a refuge of rugged terrain and few roads, the elk flourished in their rich new habitat – even in the Lolo and Lochsa areas where the Lewis and Clark Expedition nearly starved for lack of game in the region’s paltry wildlife habitat.

“By the ‘50s,” Daniels said, “the Great Burn area had the premier elk herd in the United States,” a distinction that wasn’t overlooked by popular hunting writers, such as Jack O’Connor.

“It stands out in my mind that the staff on the Superior District was proposing the Great Burn for wilderness in 1968, just four years after the Wilderness Act. That land, also called the Hoodoo roadless area, had struck those folks as such special country even at a time when the Forest Service mission was so strongly for timber.”

When the Lolo National Forest was writing management plans in the 1970s, foresters projected it would be two more decades before timber regenerating in their portion of the Great Burn would be mature for logging.

Directed by Congress, all the forests were required to evaluate roadless acres in the ‘70s and ‘80s and recommend areas to be considered for designation as wilderness, the most protective status for public land.

The Great Burn emerged strong. Even though the timber and mining industries had dug in their heels to counter the national wilderness movement, the Great Burn generally had their support because it was rugged, remote from mills and still relatively timber-poor, said Doug Gober, North Fork District Ranger in Orofino.

In the mid ‘80s, National Geographic searched North America and selected eight unique ecosystems to feature in a book, “America’s Hidden Wilderness: Lands of Seclusion.”

The Great Burn roadless area was among the chosen few, along with Utah’s Grand Gulch, the Mojave Desert and the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge.

Dale Harris, 63, of Missoula, formerly with the Wilderness Institute at the University of Montana, helped guide a National Geographic photographer through the Great Burn over six weeks.

“The burn is not spectacular for being vertical, like Glacier Park, but rather for its horizontal landscape and connectivity for wildlife,” Harris said. “The photographer had no trouble finding material. He shot 10,000 photos.”

The book was published in 1988, just before a Montana wilderness bill championed by Sen. John Melcher, D-Mont., passed Congress only to be pocket-vetoed by President Ronald Reagan in a move that helped Republican Conrad Burns unseat Melcher in the next election.

The Great Burn continues to be a victim of the stalemate the “W” word has caused between conservationists and industry in Montana and Idaho.

Current Montana Sen. Jon Tester has introduced the Forest Jobs and Recreation Act, a bill seeking to end this drawn-out dispute over wilderness in Western Montana. It does not include the Great Burn, partly to avoid political complications with its extension into Idaho.

Tester’s is the first wilderness bill introduced by the Montana delegation since 1997 – and it’s noteworthy that the bill does not include the term “wilderness.”

But there’s new hope for the Great Burn’s Wilderness-in-waiting through a group convened two years ago by Sen. Mike Crapo, R-Idaho,

The Clearwater Basin Collaborative won a national pat on the back this month for bringing conservation, recreation, industry and community groups together on public land issues, earning a $1 million federal grant to improve watershed habitat.

The CBC is on a roll, and the Great Burn is high on its agenda, said Harris, whose 40 years of wilderness advocacy was tapped with a seat at the CBC table.

“The industry is supporting a conservation agenda in areas including the Great Burn in return for consideration of land were looking at for management activity in other portions of the national forest,” said Bill Higgins of Grangeville, spokesman for the Idaho Forest Group and CBC member.

Higgins is reasonably confident that about 102 years after the 1910 fires distinguished the Great Burn, there’s likely to be a wilderness bill supported by industry and conservationists, snowmobilers and skiers – an outcome almost as epic as the Big Burn itself.