Great fire wiped out wild towns of Taft, Grand Forks

Logging outposts reviled for boozing, brothels

Back in 1910, respectable folk believed that the wild, debauched towns of Taft and Grand Forks deserved to burn in hell.

They got their wish. Both towns were wiped clean by the Big Burn of 1910.

Search for them today, and you’ll find nothing but a dusty and uninhabited freeway exit (Taft) and a tangle of undergrowth below the Route of the Hiawatha mountain-bike trail (Grand Forks).

But from 1907 to 1910, those old towns howled.

Both owed their existence to the most expensive and audacious railroad engineering feat in the nation’s history – the construction of the Milwaukee Road over (and through) the Bitterroot Range from the St. Regis River in Montana to the St. Joe River in Idaho. These rough-hewn towns sprang up overnight as work began on the line’s dozens of tunnels and trestles.

Taft was the biggest and most notorious of the new railroad towns. Its population shifted with the arrival of practically every work train, but at its height it was said to be 3,200.

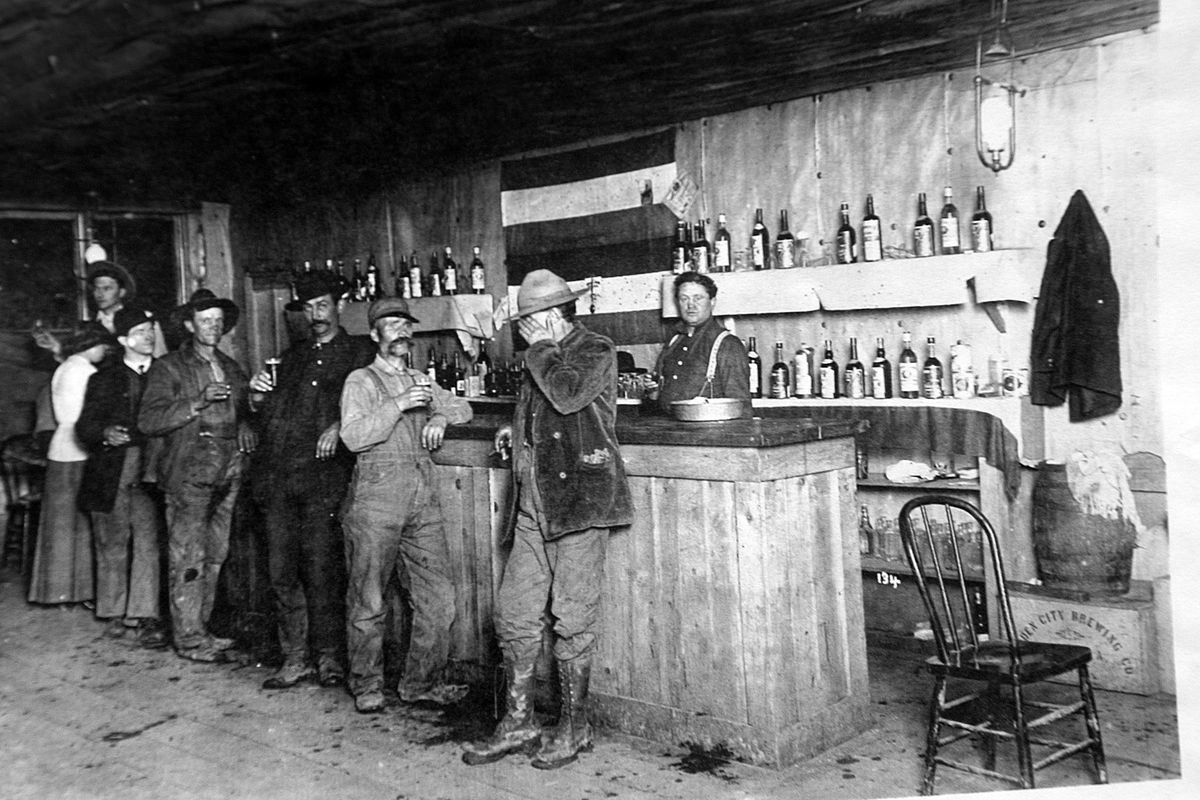

At one point the town had 23 saloons. It also had, according to one contemporary letter-writer, “300 women and only one decent one.”

They served the railroad work gangs, who were not exactly model citizens. In the spring of 1907 alone, 18 murders were committed. Sometimes, no one even knew a murder had taken place until the spring thaw came and a corpse appeared from under a snowbank.

Taft was also the scene of Balkans-style ethnic tensions. In one notorious incident, the self-proclaimed “king” of a large contingent of Montenegrin laborers was shot by a foreman. An ethnic riot nearly flared; subsequent shootouts left the foreman and five Montenegrins dead.

The very name Taft was a kind of ironic joke, according to a story told in both “Up the Swiftwater” by Sandra A. Crowell and David O. Asleson, and in “The Big Burn” by Timothy Egan (two books which provided much of the information in this story).

The story, possibly apocryphal, goes like this: In 1907, William Howard Taft, then the Secretary of War, came through the unnamed – but already notorious – work camp and stopped to make a speech from the platform of his Northern Pacific train. He berated the town as a blight and a smudge on the American landscape and told the assembled throng to clean up their act. The railroad workers gave him a big, drunken cheer (or maybe jeer) — and then, by acclamation, they named the town in his honor.

Taft burned down at least twice before the Big Burn, each time being reborn with more saloons and brothels than before.

In 1909, a Chicago Tribune reporter came through and called Taft “the wickedest city in America.”

But there was plenty of competition. When Grand Forks hit its stride, it “quickly went into first place for that honor,” said ranger William W. Morris.

Grand Forks was at the mouth of Cliff Creek on the Idaho side, down in a lush hollow far below the tracks. It was built around a muddy square, surrounded on all sides by rough wooden saloons, chow houses, boarding houses and “hotels.”

Here’s how the Forest Service’s Joe Halm – famous for his Big Burn exploits – described Grand Forks in a memoir:

“During the mornings, the court (square) was deserted except for a few sobering stragglers sitting on empty beer kegs piled in front of the 12 or 15 saloons.

“… Toward evening, the town would begin to show signs of life and as night came on and as oil lamps began to glow, player pianos began their tinny din, an orchestra here and there began to tune up. Women daubed with rouge came from the cribs upstairs and sat at lunch counters or mingled with the ever-increasing throng of gamblers and rough laborers from the camps. As the hours wore on, the little town became a roaring, seething riotous brawl of drinking, dancing, gambling and fighting humanity.”

Grand Forks had burned twice before, once in 1909 by accident and again in July 1910, when a prostitute poisoned a customer and set her room on fire to cover up the murder. By August, the town had revived in hastily built shacks, tents and even a treehouse, which became the place of business for two high-flying prostitutes.

Yet on the afternoon of Aug. 20, 1910, when the winds whipped the mountains into a roaring, red-hot frenzy, both Taft and Grand Forks were defenseless.

The saloon-dwelling population of Taft, to the disgust of the forest rangers, showed no gumption when it came to saving the town. The rangers went from saloon to saloon trying to round up men to work the firelines, but got few takers. In Egan’s words, Taft’s denizens had decided that “if they were going to be burned to death in an inferno … they would go down drunk.”

They tried to drain as much whiskey from the barrels as they could before the evacuation train came through. Everyone was staggering toward the platform when the burning embers came raining down and the trees began to topple. The train made it out just before the wall of flame hit.

There was only one fatality – a drunk whose clothes caught fire before he got on the train. A ranger rolled him in the dirt, extinguished him and hauled him to the train. When the man got to Saltese, he was wrapped in bandages and put in a dark boxcar to recover. A fellow drunk came in to see him, lit a match – and caught the man’s oil-soaked bandages on fire. He burned to death.

In Grand Forks, the inhabitants had time only to race to the train platform at nearby Falcon before the saloons, tents and shacks vanished “in a sniff,” according to Egan.

The inhabitants, along with the frightened population of Falcon, huddled at the depot, hoping a rescue train was on the way. It was. An engineer backed an engine and boxcar six miles to Falcon. The frightened people grabbed on to whatever handhold they could find and, after a harrowing trip, finally made it to Avery.

Both Taft and Grand Forks made desultory attempts to rebuild, but by 1911, the forest rangers managed to shut down the last tent saloon in Grand Forks.

Taft revived partially and served as a staging point when the Milwaukee Road electrified its line over the Bitterroots. But Taft never regained its former size or notoriety. By the 1930s, the Federal Writers Project reported that Taft consisted of only four buildings, all abandoned.

Today, travelers who take the Taft exit on I-90 won’t even see abandoned buildings. There’s a sand pile for use by freeway snowplows and some piles of old railroad ties. The old main street is covered by the interstate.

That’s more than you’ll find at Grand Forks. The green forest reclaimed it long ago. You can drive to the spot where Cliff Creek empties into Loop Creek, but rangers say you can find the old townsite “only with metal detectors.”

And what might those metal detectors find? Maybe the wires and mechanisms of old player pianos, which played their last ragtime tunes in August 1910.