Legendary radio broadcaster Paul Harvey, 90, dies

Paul Harvey, who was long considered the most listened-to radio broadcaster in the world and whose distinctive delivery and daily mix of news, commentary and human-interest stories informed and entertained a national radio audience for nearly six decades, died Saturday. He was 90.

Harvey, called “the voice of Middle America,” “the apostle of Main Street” and “the voice of the Silent Majority” by the media for his flag-waving conservatism and championing of traditional values, died at a hospital in Phoenix near his winter home, the ABC network announced. The cause was not given.

The Chicago-based Harvey was syndicated on more than 1,200 radio stations nationally and 400 Armed Forces Radio stations around the world. Harvey had not been on the air on a daily basis in the last few months, but he did do some pre-recorded segments. His son, Paul Harvey Jr., had been filling in as host.

Coming of professional age in the late ’30s and 1940s, a time when broadcasters such as Lowell Thomas and Gabriel Heatter were household names, Harvey continued to flourish in the era of Howard Stern and Rush Limbaugh.

For more than 50 years, beginning in 1951, listeners to the ABC Radio Network were greeted by Harvey’s trademark telegraphic delivery punctuated by his patented pauses: “Hello, Americans!” he’d boom into the microphone in his studio high above Michigan Avenue, “This is Paul Harvey! (pause) Stand by for news!”

He’d end each broadcast with his signature: “Paul Harvey. (long pause) Good day!”

The “Paul Harvey News and Comment” broadcasts – five minutes in the morning and 15 minutes at midday six days a week – were consistently ranked first and second in the nation among network radio shows.

Equally popular were his five-minute “The Rest of the Story” broadcasts in which Harvey told historical vignettes with surprise endings such as the 13-year-old boy who receives a cash gift from Franklin Roosevelt and turns out to be Fidel Castro. Or the one about the famous trial lawyer who never finished law school (Clarence Darrow).

Harvey’s various broadcasts reached an estimated 24 million listeners daily.

“He certainly was among the last great radio commentators,” Michael C. Keith, communications professor at Boston College and author of “The Broadcast Century,” told the Los Angeles Times in 2001.

Part of Harvey’s enduring appeal, Keith said, was his writing style, “a kind of down-home flavor yet sophisticated quality. It grabs you and holds on to you.

“His delivery was always reminiscent of the great broadcasters of the past, which made him a unique sound on contemporary radio. But he was always relevant to the present. Paul Harvey was never out of fashion. Once he came on the air, he was just irresistible. He really had you from the moment he said, ‘Page One!’ ”

He was born Paul Harvey Aurandt in Tulsa, Okla., on Sept. 4, 1918. His father was a Tulsa police officer who was killed in the line of duty when Harvey was 3, and Harvey’s mother raised him and his sister. (He dropped his last name for professional reasons in the 1940s. “Ethnic names were not very popular,” he once explained. Besides, “no one could spell it.”)

Growing up in the 1920s, Harvey developed an early infatuation with the new medium of radio, picking up stations from a homemade cigar-box crystal set.

A champion orator in high school, he was encouraged by his English teacher-coach to go into broadcasting. Beginning as an unpaid gofer at Tulsa radio station KVOO in 1933, Harvey soon began filling in at the microphone, reading spot announcements and even playing his guitar on the air.

By the time he was taking speech and English classes at the University of Tulsa, he had worked his way up to a job as a staff announcer at KVOO. Jobs at other small radio stations in Abilene, Kan., and Oklahoma City followed.

While working as news and special events director at a radio station in St. Louis, Harvey met Lynne Cooper, a student-teacher from a socially prominent St. Louis family who read school news announcements at the station.

Instantly smitten with the young woman he nicknamed Angel, Harvey later asked her to dinner. On the night of their first date, he proposed. They married in June 1940.

Lynne Harvey was her husband’s strongest supporter and his closest professional collaborator. She died last year after nearly 58 years of marriage.

While working as program director at a radio station in Kalamazoo, Mich., from 1941 to 1943, Harvey served as the Office of War Information’s news director for Michigan and Indiana. That was followed by a three-month stint in the Army, which resulted in a medical discharge in early 1944 after he cut his heel on an infantry obstacle course.

Returning to civilian life, Harvey moved on to the radio big-time in Chicago.

While broadcasting the news at WENR-AM in Chicago’s Merchandise Mart in 1951, Harvey became friends with the building’s owner, Joseph P. Kennedy. With a recommendation from the Kennedy-clan patriarch, the ABC Radio Network began using Harvey as a substitute newsman. In time, network affiliates began calling for more Harvey news broadcasts.

“If it were up to Madison Avenue, I still don’t think I’d be on the networks,” Harvey later told the Chicago Tribune. “It was grass-roots support that brought me where I am. It’s also ironic that the Kennedys, with whom I was not in agreement on so many things, had only their daddy to blame.”

Harvey’s typical broadcast included a mix of news briefs, humor, celebrity updates, commentary and the kind of human interest stories he loved to tell in order to satisfy the public’s “hunger for a little niceness.”

Known for his staunch conservatism – he called it “political fundamentalism” – Harvey supported McCarthyism in the 1950s.

In the ’60s, a time when he viewed America’s biggest problem as one of “moral decay,” Harvey echoed the sentiments of many older Americans by saying that he felt like “a displaced person” in his own country.

“I never left my country; it left me,” he said.

He blasted homosexuality, left-wing radicals and black militants at the time and reportedly was a close second to Gen. Curtis LeMay to be running mate for unsuccessful third-party presidential candidate George Wallace in 1968.

But in 1970, Harvey shocked many of his listeners with his most famous broadcast. In the wake of Richard Nixon’s expansion of the Vietnam War into Cambodia, Harvey said, “Mr. President, I love you. But you’re wrong.”

Harvey’s about-face, which he later acknowledged “was shattering to my old American Legionnaire friends,” triggered a flood of some 24,000 letters and thousands of phone calls from outraged listeners.

And while he favored the death penalty and railed against growing taxes, welfare cheats and forced busing, Harvey would again veer to the left by supporting the Equal Rights Amendment and abortion rights and criticizing the Christian right for attempting to impose their views on others.

“I have never pretended to objectivity,” Harvey told the American Journalism Review in 1998. “I have a strong point of view, and I share it with my listeners. I have no illusions of changing the world, but to the extent I can, I’d like to shelter your and my little corner of it.”

In addition to his radio broadcasts, numerous books and TV commentaries, Harvey wrote a thrice-weekly column that was syndicated in 300 newspapers, and he received up to $30,000 for speeches.

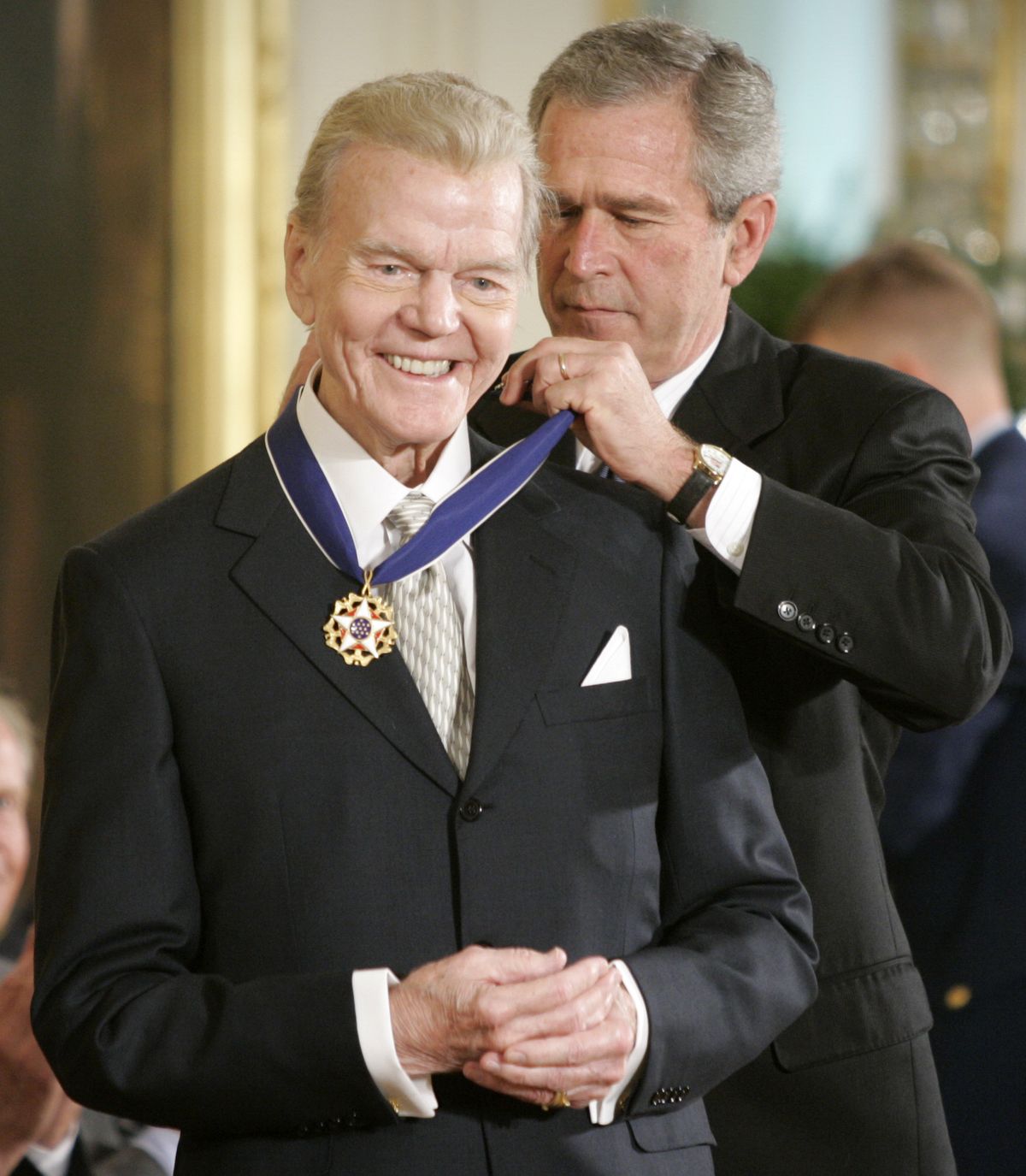

In 2005, Harvey received a Presidential Medal of Freedom, America’s highest civil award, in a White House ceremony.

He is survived by his son.