Jackson was much more than King of Pop

NEW YORK — When Michael Jackson anointed himself “King of Pop” over two decades ago, there was considerable rumbling about his hubris: Yes, he may have become a world sensation with record-setting sales of “Thriller,” and yes, he may have had a string of No. 1 hits with smashes like “Billie Jean” and “Beat It,” but the KING OF ALL POP MUSIC?

Surely, in a modern music history that has given us Elvis Presley, the Beatles, Stevie Wonder and so many other greats, that title was more than a bit inflated.

But in actuality, Jackson understated his significance.

While his elaborate, stop-on-a-dime dance moves and sensual soprano may have influenced generations of musicians, Michael Jackson stood for much more than pop greatness — or tabloid weirdness. One of entertainment’s greatest icons, he was a ridiculously gifted, equally troubled genius who kept us captivated — at his most dazzling, and at his most appalling.

At the height of his fame, he was among the world’s most beloved figures. Heads of state clamored to meet him, screen legends like Elizabeth Taylor were his close friends, and worldwide, simply the mention of his name could make people do the moonwalk, from Los Angeles to Laos. (The New York Times once accurately described him as one of the six most famous people on the planet).

His whispery, high-pitched speaking voice was constantly imitated, his fedora hat on his lean frame instantly recognizable, his childlike image endearing.

He influenced artists ranging from Justin Timberlake to Madonna, from rock to pop to R&B to even rap, across genres and groups that no other artist was able to unite. He changed music videos with “Thriller” in 1983, still considered by most to be the greatest music video ever made. Stars like Beyonce still mimic his moves. His one glove, white socks and glittery jackets made him a fashion trendsetter, making androgyny seem sexy and even safe.

Almost everyone wanted that Michael Jackson connection (and those who didn’t were afraid to say so out loud). His celebrity and adoration was staggering.

So when his image began to crumble, becoming twisted and disturbed, that aspect, too, was larger than life. His multiple plastic surgeries and his vitiligo illness, which saw him transform from a masculine looking black man to a wispy, pale-faced, almost noseless figure, was held up as the standard for bad plastic surgery, a freakish-looking character.

His eccentric behavior left people confused, and when allegations (and later criminal charges) that accused him of sexually molesting two boys surfaced on two separate occasions, people were repelled by his alleged behavior and the man that their former idol had become.

And yet, it was hard to look away.

In the early days, no one wanted to. Jackson came into our public consciousness as an impossibly cute preteen wonder in 1969, an unbelievably precocious singer in his family band, The Jackson 5. The soon-to-be Motown legend channeled songs like “I Want You Back,” and “I’ll Be There” with a passion and soulfulness that belied his young years. Even then, his dance moves, copped from the likes of James Brown and Jackie Wilson, were exquisite, and his onstage presence outshone seasoned veterans.

The spotlight began to dim when he entered his late teens, however, and while he still had R&B hits with the Jacksons, it seemed as if he would never recapture the pop success that he burst onto the scene with as a child.

But then he met Quincy Jones, and the musical landscape changed. With the legendary producer, Jackson crafted “Off the Wall,” what for most artists would be a career-defining album, from the string-enhanced disco classic “Don’t Stop Til You Get Enough,” a party staple which he wrote, to the bitter ballad “She’s Out of My Life.”

The best-selling album showed the world a grown-up Michael Jackson with grown-up artistry, showcasing his breathy alto-soprano voice and providing a springboard to his early videos, which gave a glimpse of the dance wizardry to come.

At the time, it was Jackson’s music that was front and center. A 21-year-old who spoke in a breathy, high voice, still lived at home, had his first, barely noticeable nose job and was a self-claimed virgin in an industry known for its hedonism, he was certainly an odd figure, but his personal life had yet to become intertwined with his public image.

That began to change during “Thriller” — the album that would become his greatest success and his career-defining achievement. Also produced by Jones, it featured even more of Jackson’s songwriting talents. Selling more than 50 million albums to become the globe’s best-selling disc, it spawned seven Billboard top 10 hits, including two No. 1s with “Billie Jean” and “Beat It.” It won a then-unprecedented eight Grammy awards and numerous other awards.

It was an impact measured much more than in stats.

He broke MTV’s color barrier, becoming the first black artist played on the young, rock-oriented channel when the success of “Billie Jean” and “Beat It” became so overwhelming it could not be ignored. He also established the benchmark for the way videos would be made, with stunning cinematography, precision choreography that recalled great movie musicals. Jackson’s amazing talents as a dancer were also displayed to the world during his Emmy-nominated performance for Motown’s 25th anniversary. It is still considered one of TV’s most thrilling moments, from his moonwalk strut to his pulsating pelvic movements.

But as Jackson’s fame grew, his eccentricities, from his strange affinity for children and all things childlike, to his at times asexual image to his fascination with plastic surgery, began to dull the shine off of his sparkling image. As the years went by, those “eccentricities” would become more bizarre, and completely tarnish it.

His skin, once a dark brown, became the color of paste, a transition he blamed on the skin disease vitiligo, though some believed he simply bleached his skin in order to appear more Caucasian. That belief was rooted in his frequent plastic surgeries, which whittled his nose from a broad frame to an almost impossibly narrowed bridge. His image was a tough one to look at, much less embrace.

If his plastic surgery made him disturbingly unwatchable, soon, allegations of child abuse would make him reviled among many. He was first accused of molesting a 13-year-old boy in 1993; no charges were ever filed, a civil lawsuit was settled out of court and he always maintained his innocence. Although he had a chart-topping album with “HIStory” in 1995 and was still a superstar, he was a damaged one — and would never fully recover from the allegation.

A criminal charge of molestation of another young boy in 2004, which resulted in his acquittal in 2005, further stripped his marketability and his legacy. After the trial ended, he went into seclusion, and while top hitmakers from Ne-Yo to Akon courted him to make new music, no new CD was ever released. He was overwhelmed with legal and financial troubles, with what seemed like weekly lawsuits against him seeking money owed.

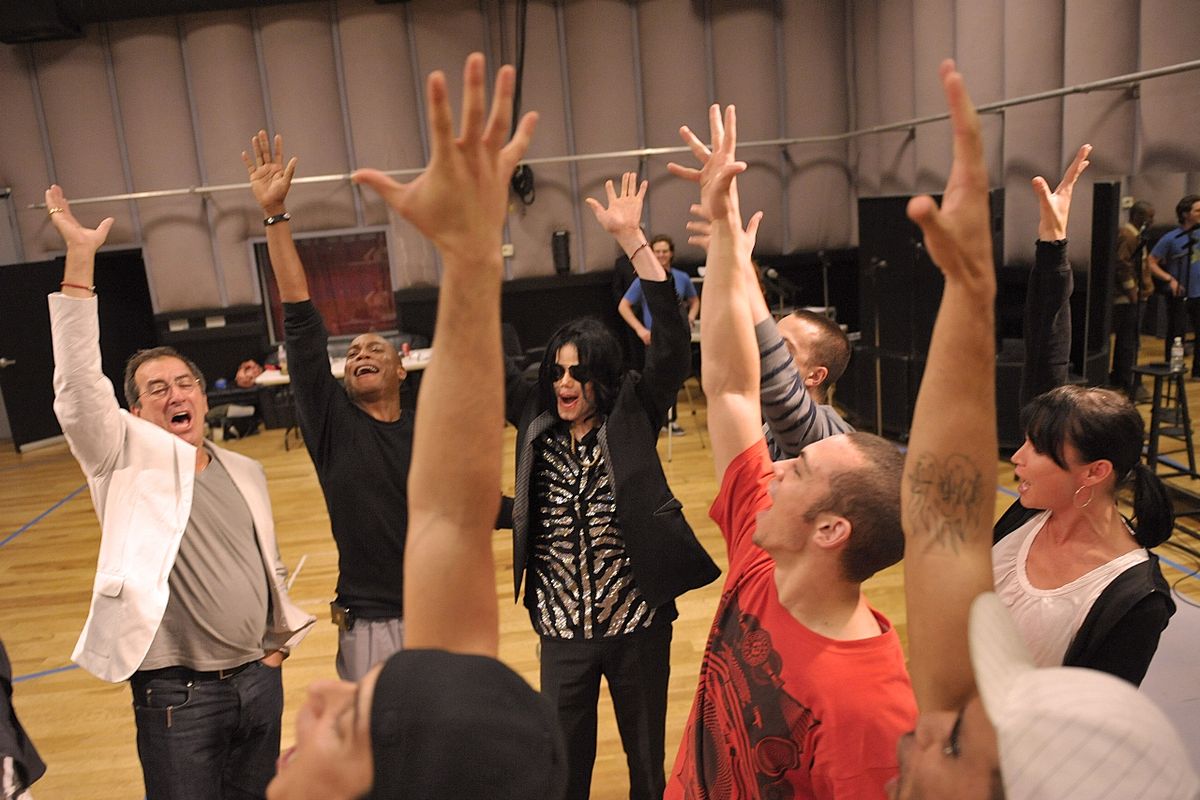

A comeback seemed to be most unlikely. His reputation was considered irreparably damaged, his image mocked and his name an automatic punchline. But when he announced he’d be doing a series of comeback concerts at London’s famed O2 Arena, not only did the initial dates sell out immediately, the demand was so insatiable he was signed on for an unprecedented 50 shows. He was expected to embark on a worldwide tour sometime after the concert series was completed in March.

Of course, there will be no comeback now, no Jackson 5 reunion, no new music to share with millions of fans. But the legacy he leaves behind is so rich, so deep, that no scandal can torpedo it. The “Thriller” may be gone, but the thrill will always remain.