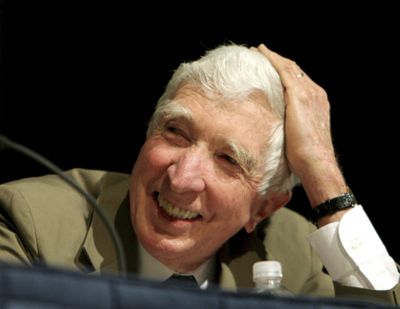

Updike, dead at 76, mirrored inner lives

Pulitzer winner was prolific, provocative

WASHINGTON – John Updike, whose finely polished novels and stories exploring the virtues, vices and spent hopes of America’s small towns and suburbs earned him two Pulitzer Prizes and kept him at the pinnacle of the nation’s literary life for five decades, died Tuesday at a hospice near his home in Beverly Farms, Mass. He was 76 and had lung cancer.

Updike was best known for peering into the bedrooms and unquiet minds of suburban couples and small-town entrepreneurs in dozens of novels and stories that mirrored America’s march from postwar optimism to the dimming dreams of a chastened generation.

Updike was often labeled the bard of suburban adultery – “a subject which, if I have not exhausted, has exhausted me,” he once said – and many of his early works of fiction were considered scandalously explicit. Updike’s reputation as a novelist and a sexual provocateur in print was secured with his novel “Couples,” which became a No. 1 bestseller in 1968. The book, which tells the intertwined stories of the longings of five New England couples, landed Updike on the cover of Time magazine under the heading “The Adulterous Society.”

“People read it as a report from the field,” the Washington Post’s David Streitfeld wrote in 1998, “wondering in amazement if their neighbors were really living such erotic lives.”

Updike’s literary reach went far beyond a study of the nation’s sexual mores. His first novel, “The Poorhouse Fair” (1959), features a 90-year-old protagonist; “Brazil” (1994) sets the timeless Tristan and Isolde love story in modern South America; and the 2006 novel, “Terrorist,” views the world through a post-Sept. 11 prism.

In one of his more popular novels, 1984’s “The Witches of Eastwick,” three women are seduced and abandoned by a man on whom they wreak devilish revenge. Updike wrote a sequel, “The Widows of Eastwick,” in 2008.

In later works such as “Roger’s Version” (1986) and “In the Beauty of the Lilies” (1996), Updike reveals his characters’ religious lives with as much unsparing clarity as he had previously unlocked the bedroom door.

He was the author of almost 60 books of fiction, poetry, essays and memoirs, turning out a new book each year. He wrote hundreds of short stories, book reviews and “Talk of the Town” vignettes for the New Yorker magazine, to which he had contributed since 1954.

“No writer was more important to the soul of the New Yorker than John,” New Yorker editor David Remnick said in a statement.

Updike’s essays – collected in 10 thick anthologies – dug deeply into subjects as varied as art history, philosophy, European and Japanese literature, movie stars and golf. His best remembered essay was undoubtedly “Hub Fans Bid Kid Adieu,” a touching 1960 evocation of baseball star Ted Williams’ final game at Boston’s Fenway Park, which Updike memorably called “a lyric little bandbox of a ballpark.”

In Williams’ final time at bat, the aging Boston Red Sox superstar hit a home run.

“Like a feather caught in a vortex,” Updike wrote, “Williams ran around the square of bases at the center of our beseeching screaming. He ran as he always ran out home runs – hurriedly, unsmiling, head down, as if our praise were a storm of rain to get out of. He didn’t tip his cap.”

Updike may have been the finest prose stylist of his generation, with a precisely calibrated command of observation, pacing and diction.

“No one else using the English language over the past 2 1/2 decades has written so well in so many ways as he,” critic Paul Gray wrote in 1982.

In “Rabbit at Rest” (1990), Updike turns his eye to something as mundane as a character munching on a bag of chips: “Keep on Krunchin’, the crinkly pumpkin-colored bag advises him. He loves the salty ghost of Indian corn and the way each thick flake, an inch or so square, solider than a potato chip and flatter than a Frito and less burny to the tongue than a triangular red-peppered Dorito sits edgy in his mouth and then shatters and dissolves between his teeth.”

But Updike’s stylistic felicity and assembly-line productivity weren’t always well received. By the 1990s, novelist and journalist Tom Wolfe called Updike “insular, effete and irrelevant,” and writer David Foster Wallace asked whether he “ever had one unpublished thought.”

Yale University literary scholar Harold Bloom said Updike could write a “beautifully economical narrative” but didn’t have the depth of other writers, such as Saul Bellow. He dismissed Updike as “a minor novelist with a major style.”

Feminists took issue with Updike’s depictions of women, who are often portrayed primarily in their relation to men. He seldom addressed directly the social issues of the 1960s, preferring to keep his attention focused on the inner motives of his characters.

“Everything can be as interesting as every other thing,” Updike once told Life magazine. “My subject is the American Protestant small town middle class. I like middles. It is in middles that extremes clash, where ambiguity restlessly rules.”