On the Wall: Exhibit pushes boundaries of photography

Hilite by Jane Waggoner Deschner (The Spokesman-Review)

Photography as an art form has progressed light years since its inception in the early 19th century, when it was developed as a tool to record people, places and events with functional, historical accuracy.

To the three photographers exhibiting at Lorinda Knight Gallery beginning Friday – Jane Waggoner Deschner, Del Lusk and Robert Tomlinson – contemporary photography is a result of experimenting with altered reality, changing what is caught on film into something entirely new, and pushing the boundaries of the medium to new places.

Jane Waggoner Deschner

Jane Waggoner Deschner knows how to make something old into something new. While you could call it photographic recycling, it is the transformation of the common snapshot.

She uses found photographs – old snapshots, the ones you’ve got cartons full of in your attic that never made it to a photo album – as her subject matter.

“They’re somebody else’s snapshots,” said Waggoner Deschner, who has collected more than 10,000 photos, snapping them up from eBay, mostly.

“They were taken for one purpose: to remember a time or place or person. Then, they get lost. When I find them, there’s sort of a resurrection.”

Lacking artistic merit on their own, these candid, quickly snapped shots, with everyday images of common themes – from sparkling ’50s kitchens to ordinary backyards – are scanned into her computer, where she digitally crops and enlarges, enhancing the composition.

In her series titled “Underneath,” Waggoner Deschner boldly inserts one or two brightly colored, flat geometric shapes, covering a portion of the black-and-white image, leaving the viewer to wonder what is blocked from sight.

“I want the viewer to look at it with a different eye,” she said.

In her “Hilite” series, she uses pale, translucent colors on circular sections of the photograph, which she duplicates and moves “to get the viewer to pay more attention.”

Waggoner Deschner, who is a graphic artist in Billings and works as a curator and gallery director at Rocky Mountain College there, said in her artist statement that she’s “working to uncover what these records of reality can teach me about our essential humanity.”

What she has learned is that there is a great sense of connection through our themes of commonality.

Del Lusk

The mind’s eye is not conditioned to Del Lusk’s imagery.

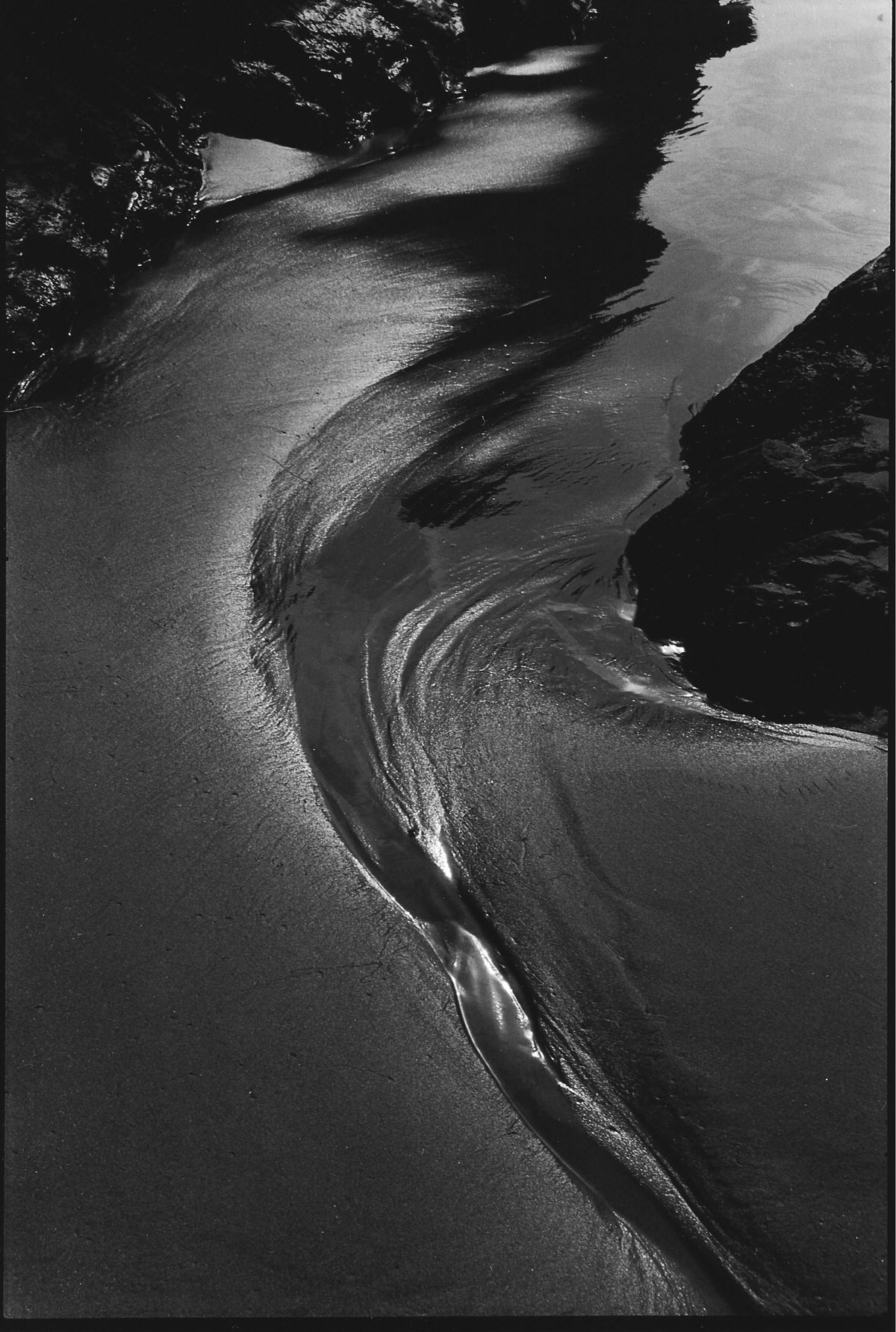

Water flowing through a landscape should be filled with light in order to be easily recognizable. Instead, an intense, chocolaty ribbon of black velvet snakes through Lusk’s photograph, with deep, dark, abstracted shadows.

With close-up views, Lusk’s black-and-white photography is more about abstract shapes and light than it is about recognizably capturing beaches and vistas on the Olympic Peninsula, where he spent hundreds of hours photographing rocks, shores and tides in full sunlight, and with full exposure.

The self-taught Spokane photographer – a retired photojournalist, writer, instructor and stockbroker – creates his moody drama in the darkroom, printing and reprinting his naturally light film images darker and darker, ensuring that even the deepest darks are still rich with definition, until he finally intuits that they are “there.”

“I’m not happy with it until it comes out in a way that gives me an emotional reaction and then I stop,” he said. “There may not be words you can say, you just feel it.”

His works have a majestic quality about them; even close views of his subjects feel expansive and create an emotional stir. Tide pools look like enchanted forests, reflecting treetops, clouds and beautiful detail in silvery still waters. Small rocks look like islands rising from the sea.

On silver print, the effect is mysterious and powerful.

Robert Tomlinson

With a background in drawing and painting, Robert Tomlinson treats his photographs like canvases – a format upon which to draw, paint, reflect, and create layer after layer.

“I make black-and-white paintings that happen to be photos,” said Tomlinson, a self-taught photographer and former art gallery director who lives in Ellensburg.

He photographs images he sees while wandering between urban settings and nature.

In the city, Tomlinson shoots graffiti and man-made markings, “not for the message or the letters, but for the drawing quality,” he said.

He combines these urban close-ups with photographs from his own well-tended gardens and botanicals he’s seen on his travels. The images are the building blocks that he uses to make his artwork.

Tomlinson alters the images in the darkroom while they are being transferred onto photographic paper. He rotates objects and plays with the timing and number of spots, using techniques like Man Ray’s solarization – turning on the light in the darkroom – to create a muted, soft, velvety look.

He adds elements like string to create white lines and ghost images. He often cuts up the prints and collages them, drawing on the printed surface with ink.

“Artists have a willingness to go into a world where you don’t know the results or what might happen,” said Lusk, who compares his process to that of a ceramicist putting a pot in the kiln.

“There’s a lot of chance, but skilled chance. You have a sixth sense. You sort of know what the outcome will be.”