Wall Street recalls Great Crash

Government reaction to today’s crisis far different

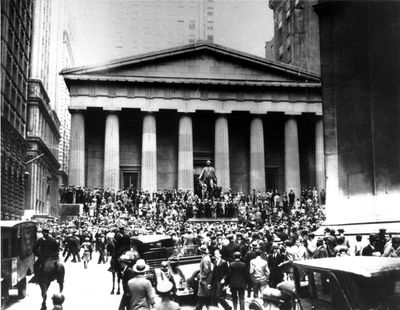

NEW YORK – Wall Street’s struggle to recover from this month’s devastating drop is coinciding with the anniversary of another dark period for the stock market — the crash of 1929.

The dramatic selling of Oct. 28 and 29 of that year sparked widespread panic and helped trigger the Great Depression largely because the government, wary of meddling in the economy, failed to take many of the steps that the Treasury and Federal Reserve are now using to try to prop up the hammered financial system.

But there are also parallels with today’s crisis on Wall Street – including missed warning signs before the crash and faltering investor confidence in the aftermath.

In the 79 years since the Great Crash, history hasn’t been kind to U.S. policymakers’ response back then, which financial experts now say reads like a blueprint of what not to do during a similar debacle.

Among the missteps: The government shrank the supply of credit through high interest rates, raised import tariffs in a botched attempt to protect American industry and hiked income taxes in the 1930s to balance the budget.

“Basically, the government did exactly the opposite of what they should have been doing,” said Sung Won Sohn, an economics professor at California State University, Channel Islands. “When we think about these things today, it’s almost ridiculous and comical what we did back then.”

The government also failed to recognize the importance of a crucial role in today’s crisis: credit. After the 1929 crash, one out of five U.S. banks failed, causing a massive contraction of the available money supply and turning “a recession into a depression,” said Vincent R. Reinhart, former director of the Federal Reserve’s monetary affairs division.

“The Fed just sat by and watched thousands of depository institutions fail,” Reinhart said. “That’s a major difference from the current policy. Now we understand the role of credit, and policymakers feel a responsibility for stabilizing that activity.”

And just like the rash of foreclosures that presaged today’s housing crisis, there were warning signs back then.

After the rough years following World War I, the unprecedented growth of the Roaring 20s sent the stock market soaring a staggering 667 percent, launching a wave of speculative-driven euphoria that experts say was clearly unsustainable. Along with stocks, a burgeoning middle class snapped up bonds, real estate and commodities like oil and coal.

But as Wall Street began crumbling and fear replaced the frenzy, investors rushed to yank their money out of one holding or another to cover mounting losses, along the way driving down the value of all of their assets.

Individual investors weren’t the only ones panicking.

Large holding companies and investment trusts – entities that existed only to hold stock in other companies – began buying up shares in their own company in a desperate bid to survive – a move economist J.K. Galbraith later described as an act of “fiscal self-immolation” in his book, “The Great Crash of 1929.”

Many market historians believe the crash started on Oct. 24, when heavy selling swept the market. But the two days labeled Black Monday and Black Tuesday, Oct. 28 and 29, are widely considered in popular culture as the days that the crash occurred.

Those two days rank as the second and third largest one-day percent losses for the Dow, with declines of 12.82 percent and 11.73 percent, respectively.

The Oct. 19, 1987, loss of 22.61 percent remains the largest one-day percentage drop, though the market’s current decline smashed the previous record for the largest daily point drop with a 777.68-point plunge Sept. 29. In an eight-day losing streak earlier this month, the Dow lost a stunning 2,400 points, or 22.1 percent.

Experts have largely praised the government’s reaction this time around, and say it should keep the economy from falling into another depression.

For starters, Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke, a former academic and expert on the Great Depression, has aggressively cut interest rates and pumped billions of dollars in liquidity into the financial system to keep the supply of money from drying up.

The tactic, known as a “helicopter drop,” is borrowed from famed economist Milton Friedman. Bernanke touted the practice in a famous 2002 speech, leading critics to sometimes refer to him as “Helicopter Ben.”

“The idea is that if people have access to extra liquidity, some portion of that will be spent,” stimulating the wider economy, Sohn said.

Another decision that may have averted catastrophe was the Treasury’s $700 billion emergency plan to remove banks’ troubled mortgage-related assets as well as taking equity stakes in banks in a move designed to get stagnant lending going again. That, experts say, has so far helped avoid the wave of bank failures that preceded the Great Depression and has helped keep credit available if not easy to obtain.

But as these uncertain times show, the government can’t fix everything.

Even with the sweeping government rescue plans, stock markets around the globe have continued to tumble, including a worldwide plunge on Friday from Tokyo to New York. Experts say the persistent fear in markets is a reflection of the limitations of American economic power in an increasingly globalized world.

“Today you have the Federal Reserve sending good signals to the market, but there are lots of other types of bad news out there that is hard to control,” said Eugene White, an economics professor at Rutgers University and an expert on the 1929 crash.

As an example, he mentioned the banking collapse earlier this month in Iceland, which wiped out investors across Europe and sent waves of worry around the globe.

In the old days, “who would have thought that would be a problem?” White said.

Just like during the Great Depression, he said the current crisis will leave a legacy by forcing U.S. consumers to cut back on borrowing and spending.

“People are going to feel less wealthy and they’re going to consume less,” White said.