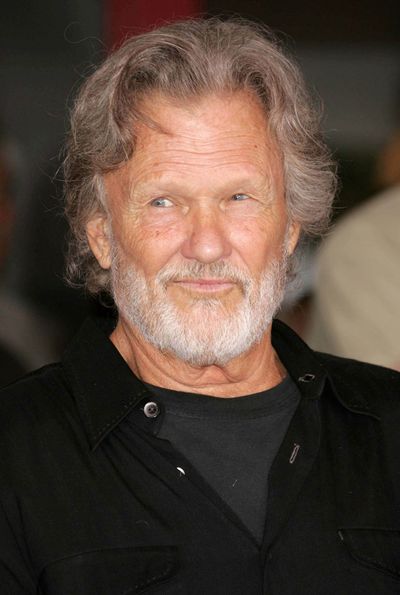

An odd journey to fame

At 72, Kristofferson has mastered just about everything

Rhodes scholar. Army captain. Helicopter pilot. Actor. Country superstar.

Kris Kristofferson has done it all.

“When I look back on it, I’m kind of amazed that I wasn’t more amazed,” said Kristofferson, his speech punctuated freely with throaty laughter. “I’ve met some amazing people and been close friends with a lot of them. … And I got to do a lot of different things.”

The 1970s icon behind such hits as “Me and Bobby McGee,” “Help Me Make It Through the Night” and “Sunday Mornin’ Comin’ Down,” Kristofferson took a twisted path to fame.

After earning a master’s degree at Oxford University and rising to the rank of captain in the Army, Kristofferson turned down a professorship at the U. S. Military Academy at West Point to pursue life as a Nashville songwriter. He swept floors at Columbia Studios, worked as a commercial helicopter pilot in Louisiana, and started pitching songs on Music Row.

It took a few years, but Kristofferson finally made it – thanks in part to Johnny Cash.

The rest of Kristofferson’s life – his movie career, his romance with Janis Joplin, his famous friendships – is music industry legend.

He has released more than 20 albums, including 2006’s “This Old Road,” and won three Grammy Awards and a Golden Globe. He’s been inducted into the Songwriters Hall of Fame and the Country Music Hall of Fame. Last year, he received the Johnny Cash Visionary Award, given by cable network Country Music Television.

Now 72, Kristofferson splits his time between touring as a solo artist and film and television projects.

“I feel kind of blessed to able, at this age, to do what I love to do for a living,” he said.

We recently interviewed Kristofferson by phone from Malibu.

Q. You were a janitor at Columbia when Bob Dylan was recording “Blonde on Blonde.”

A. It looks now like it was a wonderful coincidence.

At the time, there were a lot of people (who) thought I’d lost my mind. I had a Rhodes scholarship and graduated from Oxford and had a career as an officer in the army. And to go from there to being a country singer, or trying to be, and just being a janitor at a recording studio, a lot of people thought I had lost it, just had no idea what I was doing.

But I was very fortunate. I got to be close friends with Johnny Cash, and I got to be one of the only guys at the Dylan session. They had police around the building keeping the songwriters out.

Q. That was as you were launching your songwriting career.

A. For two years every other week I was flying on the offshore oil rigs down in the Gulf of Mexico. And I had to leave that job because of my lifestyle during the times that I was off, trying to pitch my songs. … Johnny Cash had a big important television show that was starting in Nashville and the next thing you know, (songwriter) Mickey Newbury and I were the mascots of the show. … I never had to work again.

That was like four years after I’d come to town … I was just in love with that life and hanging out with other people who were serious about songwriting, who felt like it was an important thing.

When I think about people I should be grateful to, (Bob Dylan) was the one that made songwriting, to me, a respectable thing. It was an art form that was worthy of you dedicating your life to it.

Q. When did you become an actor?

A. The (movie) opportunities came just as the same time I was getting the opportunities to sing my own songs. I got a job at The Troubadour (in Los Angeles) and it got a great review … and next thing you know all these movie people were there, and I was getting scripts offered to me. God knows how all that happened.

Q. Making the transition from music to movies must have been intimidating.

A. I was no more intimidated than I was to get onstage. I was a little scared of both of them, but what worked onstage seemed to work in the films too: to make people believe you’re telling the truth. … It worked better in some cases than in others, but I felt really lucky to be at the right place at the right time.

Q. Talk about The Highwaymen, the supergroup you formed with Cash, Waylon Jennings and Willie Nelson.

A. They were my heroes before I ever came to town. … I was close friends with them and got to be on the same stage with them and sing songs with Johnny Cash whether he liked it or not. Each one of them had a great sense of humor. They were great artists. And it’s one of the best parts of my life. I wish I had known that our time together was going to be so short, but still it was just a wonderful experience …

When I went (to Nashville), all the serious songwriters loved Willie Nelson but his own record company didn’t believe that anybody would ever buy his record. People thought he was too unusual for a country audience. But he’s the biggest thing there ever was.

The great thing about country music is the great thing about soul music, is that it comes from the heart and the real stuff will always survive.

Q. These days you’re touring as a solo performer. How is that going?

A. When I was starting out, I never had the nerve to go out without a band. I always had some friends around me, and I had a great time doing that. But it’s kind of nice being free to make a mistake without causing a train wreck. … As you get older, people get to treating you like an old friend, not quite as ready to throw things at you.