His latest challenge

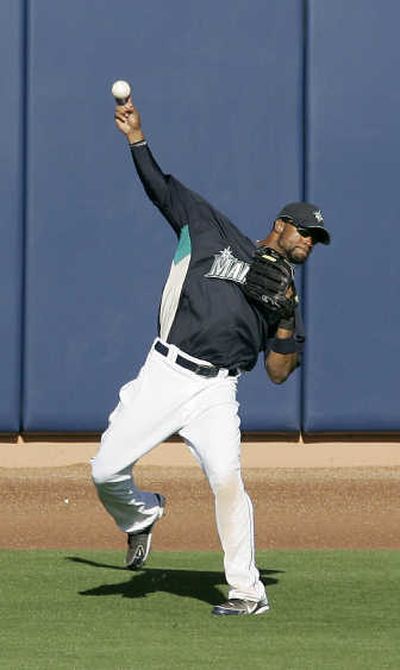

PEORIA, Ariz. – It figures that Charlton Jimerson is trying to run his way onto the Mariners.

Jimerson has been ignoring stop signs his entire life.

“It’s something I’ve proven to be able to do – at all levels,” the 28-year-old said of his speedy attempt to make his first major league team out of spring training, 12 months after he was unemployed and cold-calling teams using a directory from a magazine.

His mother abandoned him for crack cocaine. His father left before that. His sister, Lanette, got a court order to raise him and his brother in and around Oakland, Calif., when she was 19.

Jimerson applied to the University of Miami solely on academic merit after he saw a “commercial, a real good commercial” about the school, its beach and its sun.

He walked on to the Hurricanes soon-to-be national-champion baseball team – even though the coach had never heard of him. Without a scholarship, he cobbled together loans and grants to earn a degree in computer science.

“I’m still paying off my student loans,” he said, not laughing.

En route to the degree, Jimerson replaced his roommate, an injured star outfielder, and became MVP of the College World Series.

The Houston Astros drafted Jimerson in the fifth round in 2001. When they waived him last March, he cold-called the personnel directors and minor league coordinators from 30 big-league teams.

Days, weeks, nearly a full month passed before his phone rang.

“Seattle actually called me,” he said.

The Mariners answered solely because Jimerson had played in 18 major league games in 2005 and ‘06. They had no clue of his ambition, which has trumped the cards life tried to deal him. They knew nothing of his quick first step – the one off first base that has kept Jimerson ahead of a life that easily could have dragged him tragically down.

“We just needed a player at Double-A,” said Mariners director of player development Greg Hunter.

Now, after hitting 25 home runs and stealing 35 bases at Double-A West Tennessee and Triple-A Tacoma last season to earn a September call-up, Jimerson is a week from willing himself onto a playoff contender in the A.L. West.

Jimerson is in a fight with Mike Morse, Wladimir Balentien and former starter Jeremy Reed for the backup outfielder job. He hasn’t been the spring hitting star Morse has been, but his hook is as the base-stealing specialist Seattle has rarely had. He leads the team with four stolen bases this spring.

Jimerson is 4 for 4 on steals in two stints in the big leagues – 11 games with the Mariners last season and 17 games for Houston. He stole 30 bases in 39 tries at West Tennessee last season, then was 5 for 6 at Tacoma.

That’s an 80 percent success rate the last two seasons, a number that fits Mariners manager John McLaren’s run-more mandate like a favorite pair of running shoes.

Jimerson doesn’t want to look like an eager kid over making the team. He is, after all, 28, a husband and a father to 11-year-old Alexa and 14-month-old Tyson. His locker is between those of Morse and Balentien. So he plays it cool.

But Lanette knows.

“This would be the first time starting the season with a team, making the 25-man roster,” she said by telephone from her home El Cerrito, Calif. “I would say he’s pretty, pretty excited.”

Lanette was 19 and a college student working three jobs when a court order made her guardian of Charlton, then 14, and his 8-year-old brother, Terrance. Their father had left. Their mother’s drug addiction led her to sometimes leave the young boys stranded at pizza shops, arcades or street corners.

“I learned what a budget was,” said Lanette, who took parenting classes and found friends or shelters to take in the family for safe sleep. “I learned how to cook so not everything was just fast foods. My brothers are very good kids. It wasn’t like they were a burden.”

Houston initially drafted Charlton in the 24th round in 1997 out of high school, and he wanted to quit school then. Lynette talked him out of it. She felt Charlton had to get away from his past, so she made him agree to go to a four-year college at least a six-hour drive or one-hour flight away. When USC didn’t accept him, Jimerson chose a six-hour flight.

Before he even knew where the student union was on the Miami campus in Coral Gables, Fla., he went to the baseball office. Tryouts wouldn’t start for another few days, but Jimerson spent an entire day there, uninvited, meeting coaches and players.

He made the team but spent years on the bench. Coach Jim Morris advised him to transfer. But then his roommate, Marcus Nettles, got hurt. Jimerson hit leadoff home runs in each of the first two games of the 2001 College World Series and ended up MVP of the series, which the Hurricanes won.

On Sept. 4, 2006, at Philadelphia, Jimerson pinch-hit for Roger Clemens and hit a home run in his first major league at-bat. It broke up Cole Hamels’ perfect game with two outs in the sixth inning. But he never stuck. He said Houston expected too much, too soon.

“Run, throw, hit, play defense. Who am I supposed to be, Barry Bonds?” he said, leaning forward in a stool at his locker in the back corner of Seattle’s clubhouse.

Now he feels unburdened by the Mariners allowing him to just run and play.

Lanette said she and her brothers are trying to repair their broken bond with their parents, who both live in Oakland.

Jimerson is reluctant to talk much about that. His sister says of Charlton and his dad: “It’s fair to say there’s definitely a relationship there. But it’s hard to define.

“Still, there are some things you can’t make up for, you know?”