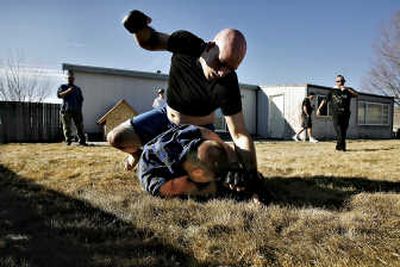

Backyard brawlers fight for the thrill of it

YAKIMA – The thing that stands out is the blood.

It’s not the friendly banter between Vengeance and Nasty Rob as they exchange blows. It’s not the assorted characters cheering the fight, although little Ricky with the mohawk is probably worth his own story. It’s not the thud, the deep, hollow sound of 450 pounds of two bodies hitting a dead lawn.

It’s the blood, pouring down Nasty Rob’s face and clogging his nose. Blood dripping onto the grass and the walkway. Blood stifling his breath to the point where he has to quit. That’s what everyone is here for. That’s why people will watch this fight when it’s posted on YouTube.

It’s the blood.

It took awhile to get here, to this dusty lawn outside of Selah. The afternoon started with a pair of clandestine meet-ups in parking lots – the two fighters, the cameraman and a few friends – before everyone jumped in cars and followed one another here. The fact that the participants won’t give their full names adds to the air of secrecy.

But, despite the cloak-and-dagger, everyone involved knows the whole thing will be viewable by anybody with a computer. The fight will be posted to YouTube, where it will join about 22,000 videos of backyard and street fights from around the world. Those who object to its underground nature can watch the sanctioned version on cable and, starting next year, on CBS in prime time.

And people will watch.

“It’s built-in,” said Joanne Cantor, a University of Wisconsin professor who studies the effects of violent media. “We are designed to have our attention grabbed by violence.”

That attraction is deeply rooted, according to Jay Grewall, a Los Angeles multimedia freelancer working on a documentary about fighters’ psychology. The backyard fights that organizers Malcolm and Joe stage for their camera are designed on the mixed-martial arts model that has become a television bonanza via leagues like Ultimate Fighting Championship and Elite Extreme Combat. They have the same combination of striking and grappling, the same tendency to end quickly with one or both fighters bloody. And, according to Grewall, they have the same everyman appeal.

“Anybody can do it,” he said.

It’s not surprising, then, that people click on Web sites to watch the fights, Cantor said. Some people will be disgusted by the violence, and others enthralled, she said. The danger, for those who are enthralled, will be in failing to distinguish this real violence from the staged violence of movies and television. That leads to desensitization and failure to understand the real potential for negative outcomes, she said.

It’s easy to forget, watching a fight through a computer, that the fighters are real people bleeding real blood.

Nasty Rob, a 22-year-old bouncer and dishwasher, is introspective and amiable when he’s away from fighting.

Vengeance is a 22-year-old named Jeff who’s played drums for a couple of local bands and works cutting plastic. He’s got a MySpace page laced with aggressive language and threats of revenge against his enemies. But the page also has a picture of his fiancee and another of him holding his newborn daughter.

“I’m not really the violent type,” he says in an interview days after the fight. “It’s just for the sport of it. I love the sport. I love nothing more than to just get out with a bunch of people and just have fun. Whether it’s football or hockey or just beating the crap out of each other.”

That otherwise regular guys would spend their weekends risking their well-being is not the contradiction it may seem. Grewall, who has interviewed dozens of professional and amateur mixed-martial arts fighters for his film “If Mother Only Knew,” has seen doctors and teachers strap on the sport’s thinly padded, fingerless gloves.

Aggression is, as Freud said, an elemental part of the human psyche. And modern society doesn’t offer many opportunities to let loose that id, says Gordon Marino, a philosophy professor at St. Olaf College in Minnesota.

“That you don’t really become alive until you risk yourself in combat, that’s an ancient idea,” said Marino, who teaches boxing and writes about the sport for publications such as the Wall Street Journal. “And there’s no place for people to do that.”

About a dozen people, virtually all male and virtually all in their 20s, ring the patch of brown yard that will serve as today’s arena. The rules, decided by the fighters just before they start, stipulate three-minute rounds with one-minute breaks. As many rounds as it takes until one of the men quits. No eye-gouging. No hair-pulling or biting. No intentional groin kicks.

They square up and shake hands.

“Hey man,” Vengeance says. “Win, lose or draw – beers after.”

Then it’s on. Vengeance is all over Nasty Rob immediately, landing shots that snap his head back and drawing shouts of “Hit him!” and “Yeah!” from the assembled crowd.

But Nasty Rob is game. He doesn’t look like an athlete the way Vengeance does; he’s more like a lumberjack. It’s hard to tell whether he even notices the pummeling he’s taking early. Then he’s fighting back. At about 245 pounds, Nasty Rob outweighs Vengeance by about 40. When they go to the ground, he almost wins the fight using that weight. He gets Vengeance in a choke-hold – “I pretty much started seeing stars and was about to pass out,” Jeff says later – but can’t quite hold it long enough to end the fight.

By round three, both men’s arms are heavy. The action slows.

Then – thud – Vengeance has Nasty Rob on the grass. He’s on top, landing furious shots to the head. There’s the blood. Nasty Rob can’t breathe, can’t continue. He taps out, slapping the ground to signal that he quits.

Rob takes a minute to get up. Then he and Vengeance embrace.

“I gotta admit, this is what I love the most,” says Joe, who acted as referee while Malcolm filmed the fight. “When they’re both sitting there afterward in mutual respect.”

Days later, Rob says he’d love to fight Jeff again. It isn’t about winning a rematch; it’s just about fighting, he says.

“I have not found a feeling that can match getting into a fight,” Rob says. “When I strap on those gloves for those three minutes, I’m not worrying about anything. I’m not worried about rent coming up. I don’t have to worry about anything but what’s in the moment. … I honestly don’t know how to explain it, but it is an extremely euphoric experience.”