Spunky activist, last native Eyak speaker dies

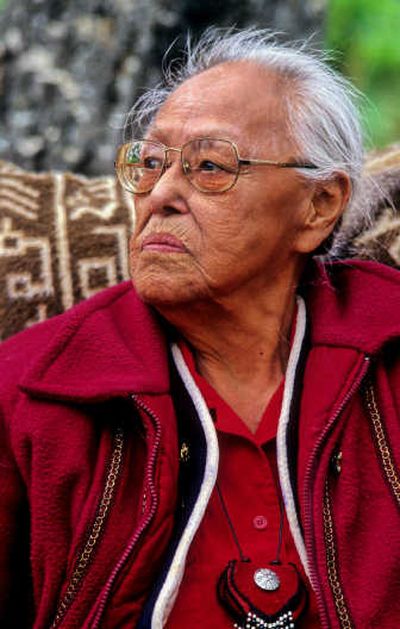

ANCHORAGE, Alaska – Chief Marie Smith Jones, the last full-blooded Eyak and last native speaker of the Eyak language, died Monday at her Anchorage apartment.

She was 89.

According to her son, Leonard Smith, she was found in her bed. Her family believes she died in her sleep.

“Everyone is like, she not in pain anymore,” said granddaughter Sherry Smith. “Because she has been in pain a lot.”

Smith Jones was well known in Alaska and beyond as an activist – a feisty one. She took on her native corporation in a fight against clearcutting on ancestral lands. She oversaw the repatriation of bones when the Smithsonian Institution was forced to give them back. And she spoke at a United Nations conference on indigenous peoples.

She was a tiny woman who smoked like a chimney and wasn’t afraid to say exactly what she thought. And reporters far and wide wanted to know.

She once told a writer from the New Yorker who knocked on her door to buzz off. She reconsidered when the fresh halibut brought as tribute wouldn’t fit in her mailbox, leaving her no choice but to open the door.

“My mom had more spunk,” said Bernice Galloway of Albuquerque, N.M. “And don’t get in her way when she makes up her mind about something.

“She has been an activist for Indian rights and the preservation of natural resources, for the native way of life.”

It wasn’t until Smith Jones was in her 70s, after her sister, Sophie Borodkin, died in 1992, that she stepped up to the plate. Her sister’s death left her as the last fluent native speaker of the Eyak language. When that New Yorker lady asked how she felt about that, Smith Jones put it this way:

“How would you feel if your baby died? If someone asked you, `What was it like to see it lying in the cradle?’ “

Smith Jones wasn’t too fond of such questions. Or reporters.

“She’d become something of a poster child for the issue of mass language extinction,” said linguist Michael Krauss, founder of the Alaska Native Languages Center and now retired from the University of Alaska Fairbanks. “She understood, as only someone in her unique position could, what it meant to be the last of her kind. And she was very much alone as the last speaker of Eyak.

“It’s the first, but probably not the last at the rate things are going, of the Alaska native languages to go extinct. She understood what was at stake and its significance and bore that tragic mantle with grace and dignity.”