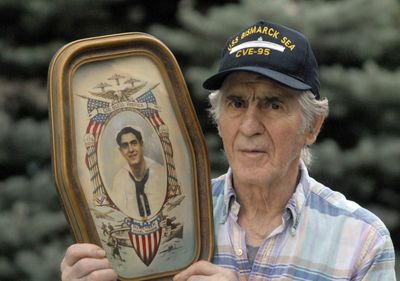

‘God had a plan for me’

Post Falls man survived kamikaze hit, night in ocean

Ernie Peluso has survived much in his 83 years of life – serious falls, car accidents, hunting accidents and a kamikaze attack that sunk his aircraft carrier during World War II – but he’s not sure why.

“I guess God had a plan for me. But I don’t know what it was,” the Post Falls resident said when searching for a reason why he lived through the sinking of the USS Bismarck Sea and a night alone in the South Pacific during the battle of Iwo Jima.

Peluso was a sailor who had lied about his age to enlist in the Navy. One of 12 children of immigrant Italian parents, he didn’t speak English until he was 6 and quit school after the seventh grade. In October 1942 he was working in a small auto parts factory in Newport, Ky., across the Ohio River from Cincinnati. One brother was already in the Navy, another was in the Army, and Peluso decided he didn’t want to wait an extra month to join.

“I was told if you get in a little earlier, you’d get on a big ship,” he said. It was, he added, “pride, mostly.”

He dropped a digit from his birthday month – telling recruiters he was born in January rather than November – and got in.

After his training, he was sent to Bremerton to await assignment to a large ship in Alaska. While there, his barracks had an air raid drill, and all the sailors scrambled for different exits. He went out a door that had nothing on the other side but an open shaft. He fell into the hole, lost consciousness and lay there for hours. He spent four days in the hospital before doctors determined he’d broken his back, then spent three months in a neck-to-hips cast.

By the time he was fit for sea duty, the ship in Alaska had sailed and eventually he was assigned to the USS Candid, a minesweeper. After a few months he asked for a transfer: “It was too small a ship.”

The Navy assigned him to a new aircraft carrier. The USS Bismarck Sea was an escort carrier, which meant it was about two-thirds the length and width of a standard carrier like the USS Saratoga. But with 28 planes – mostly torpedo bombers – and a crew of more than 900 men, it was a big ship to a teenager from a small town in Kentucky.

The ship spent much of the second half of 1944 on convoy duty in the South Pacific, and in early 1945 was ordered to Iwo Jima as part of the huge armada headed for the small volcanic island at the southern tip of Japan, where Marines would make their historic amphibious landing. Most of the time Peluso was an ordinary seaman, assigned to whatever task needed doing. When the fleet was under attack, he manned a turret with twin 40 mm guns on the ship’s aft port – the back left.

That’s where he was the evening of Feb. 21, 1945, the fifth day of the battle of Iwo Jima, when about 50 Japanese kamikaze planes descended on the fleet.

“We looked straight ahead of us, and there was a big ball of fire. It was the USS Saratoga got hit by a suicide plane,” he said. The Saratoga would eventually be hit by five kamikaze planes, but stay afloat.

Another suicide plane was coming in low toward the Bismarck Sea, and they couldn’t fire at it without hitting other ships.

“I seen one going by and I could see he had a white band around his forehead. He was about 5 feet above the water and we couldn’t swing our guns down that far,” Peluso said. “He was coming in low and off at an angle … just about even with us.”

The Japanese plane dove through the flight deck and exploded on the hangar deck below. “When he blew up it about busted my gun spot in half.”

Peluso got orders to report to the bridge. On the way up he passed a chaplain who was giving last rites to a dying sailor. “While I was watching him – I think he was about 100 yards off – a (munitions) magazine blew up and killed him and blew the sailor apart,” he recalled.

A second kamikaze plane hit the ship on the port side at the waterline. Explosions rocked the carrier as the stocks of ammunition, replenished recently for the Iwo Jima assault, began to detonate. The carrier was taking on water and listing to the right when the captain ordered the crew to abandon ship.

Peluso realized he didn’t have his life jacket. He always took it off to operate the gun, and had left it at his battle station when the call came to report to the bridge.

“Another sailor who was standing there said, ‘I’ll jump in, you jump in after me and you can hold on to me.’ So when he jumped, I jumped real quick,” Peluso said. “I went down, straight like a bullet, 60 feet.”

He hit the water but couldn’t find the sailor, so he swam toward the back of the ship where he spotted an empty life raft floating on the water and grabbed onto the side.

“About 20 sailors come right by and grabbed on to me. They were pulling your hair out and everything else, trying to get on the life raft,” he said.

Eventually he decided to swim away from the raft and go off on his own. After about 20 minutes there was no one else around. It was dark. Night had fallen, and the only light had been the fires burning on the Bismarck Sea, which had sunk. For nearly 12 hours, Peluso dog-paddled alone in the ocean without seeing or hearing any other survivors.

In the early morning he spotted a destroyer coming toward him. The ship lowered a cargo net for him, but his arms were so tired he couldn’t get them out of the water; two sailors had to climb down the net and pull him up.

“They put me on deck by a 5-inch gun turret and gave me a cup of coffee. I kind of blacked out.”

There were no other survivors of the Bismarck Sea on board, just 39 bodies the destroyer had pulled from the ocean. Peluso didn’t know if any of them were his friends because they were in sacks. The next morning the destroyer crew held a mass burial at sea, and one by one the weighted sacks were slid down a board ramp into the Pacific.

“It’s kind of hard to explain,” Peluso said, recalling the ceremony. “You look at ’em and say, ‘I’m glad it’s not me.’ ”

For weeks, Peluso believed he was the only survivor of the Bismarck Sea. “What you do, you stop thinking. … I just started doing what I was doing, trying to survive.”

He was eventually transferred to a transport ship and put to work loading and unloading supplies for the Marines on Iwo Jima. He’d lost one of his shoes during his night in the Pacific, and the ship’s crew tried to find him a replacement. They could only find a pair of size 12s; he wears size 8. He did most of his work wearing just one shoe.

After about two weeks off Iwo Jima, he was shipped to Saipan and a few days later put on a transport ship to Pearl Harbor. It was there, at a survivor’s station, that he learned he wasn’t the only survivor of the Bismarck Sea and was reunited with some of his shipmates. In fact, although 318 men died, about two-thirds of the crew survived and were picked up by other ships.

All his records and belongings went down with the ship, and the Navy essentially lost track of Peluso for several weeks. His family was told he was missing in action and wasn’t notified he had survived until Peluso arrived in Pearl Harbor. Eventually he was sent home on 30 days leave before being told to report to a Navy base in Jacksonville, Fla. He stayed in the United States on shore duty for the rest of the war.

By November 1945, Peluso was ready to get out of the Navy, return home and get on with his life. He signed a waiver that he says kept him from receiving a disability pension for his injuries from the fall in Bremerton and was released.

He returned to Kentucky and thought about going back to school on the GI Bill; instead, he met a girl, got married and began raising a family.

He got a job at a Kaiser Aluminum plant. He also began visiting a brother who lived in Spokane, to hunt deer and elk. After a few trips, his brother pointed out that Kaiser had aluminum plants in the Spokane area, too. “Why don’t you just move up here?” his brother said.

In 1949, he did. Peluso worked at the Mead smelter for 34 years. He and his wife, Geraldine, raised 13 children on a small farm in Chattaroy, then moved to Post Falls in 1994. Three sons served in the military, and one is just finishing up a 22-year career in the Army.

The Pelusos have 32 grandchildren and 20 great-grandchildren – so far. The family is “scattered all over the country.”

Looking back on the war, much of it seems pretty senseless, he said. But when he thinks about why he survived the sinking of his ship and a night in the ocean, maybe those children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren are the reasons.