A leader, a fighter

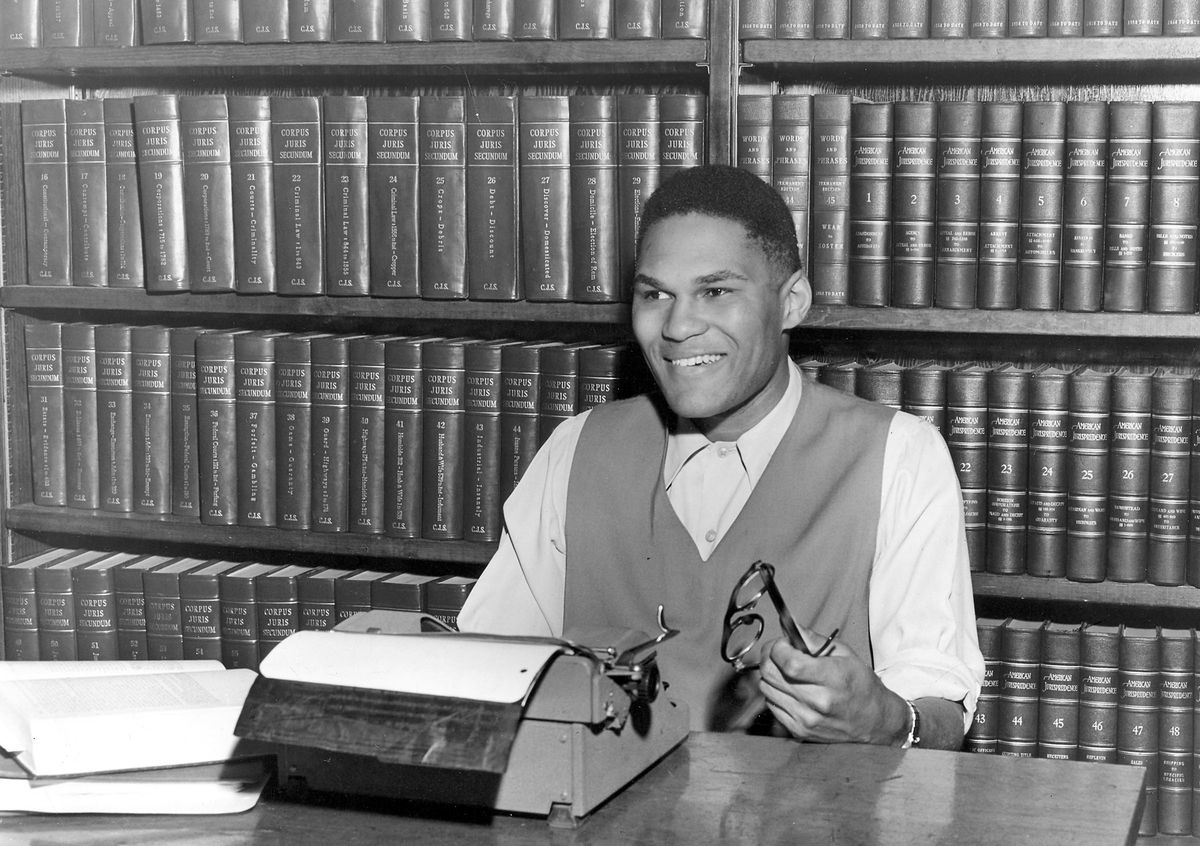

From the boxing ring, to the courtroom, to his work during the civil rights movement, Carl Maxey became a legend in Spokane

Note: The following three excerpts are from a newly published biography of Carl Maxey (1924-1997), Spokane’s well-known attorney and civil rights leader, written by Jim Kershner, who is also a staff writer for The Spokesman-Review. In this passage, the board of a Spokane orphanage has just voted unanimously to kick out Maxey and his best friend, Milton Burns, and “to have no more colored children in the home from this time forward.” The year was 1936, and Maxey was 12 years old.

As Maxey remembered it, he was just plain tossed out on the street. “I ran around until they caught me after a while,” he said, some sixty years after being evicted from the orphanage. Under some circumstances, Spokane might have had its attractions to a young boy on the loose: the ballpark at Natatorium Park, where Babe Ruth had recently come through on a barnstorming tour; the Nat Park ballroom, where black patrons were admitted only when the musical star was black (Fats Waller, Louis Armstrong, and Duke Ellington all played there); and the vaudeville houses downtown, where a young Spokane singer named Bing Crosby had recently learned his trade before going on the road to Hollywood.

But in 1936 the reality was far starker. The Great Depression was at its height. The mining industry was half dead and the demand for timber had crashed right along with the housing market. Unemployment in the city hit 25 percent. Tent cities and shanty towns mushroomed in the railroad yards and beneath the big bridges spanning the Spokane River. Packs of unemployed men haunted the rail yards, hiding from the “bulls” – the hired guards – whose purpose in life was to keep the hoboes off the freight trains. And these hoboes weren’t all adults. “Hundreds of them are boys and girls, as young as 10 years, who are traveling in bands,” wrote Spokesman-Review reporter Margaret Bean, who visited the rail yards and hobo jungles in October 1932. “With a through freight, composed of 100 cars, it is impossible for a freight car to keep this swarming army from crowding their train, especially the mobs of children. They are too agile for a train crew. Chase them from one empty car and they are half a mile down the train and scrambling into another.”

Refugee farmers from the Dust Bowl wandered the city only to find that eastern Washington was suffering its own record-breaking drought. Large portions of Spokane – like much of the hard-hit Northwest – had a hangdog air. If there was ever a good time for a twelve-year-old black kid to be wandering aimlessly through Spokane, this was not it. “I can’t imagine why nobody in the black community didn’t take him in,” said Lou Maxey. “But, at the time, I guess I can. Nobody had any money.”

Some tried their best to help. Mildred Elliott, who was a child at the time, remembered her mother marching up to the door of one of the Catholic children’s homes in Spokane and asking them to take Carl in. In fact, “asking” is hardly a strong enough word. She begged them. “They said, ‘No, we don’t take colored,’ and the nun slammed the door in my mother’s face,” said Elliott. What could a black woman do in the face of that? She turned around and made the long trudge home. She didn’t have a nickel for the trolley ride.

In any case, Carl probably didn’t remain on the street for very long. Milton Burns, his one and only companion through these times, said that he doesn’t remember being out on the street long, if at all. “We went straight to the juvenile home [the Spokane County Juvenile Detention Center],” said Burns. “There was no other place for us to go, because we were county charges.” The juvenile detention center was in a built-on annex next to the bizarrely chateau-esque Spokane County Courthouse, which loomed on the city skyline like a misplaced French fairyland castle. Burns remembered the detention center as a home to twenty or thirty kids at most, the majority of whom were juvenile delinquents of varying degrees. Maxey and Burns were two of the youngest and definitely two of the most innocent inmates. “We hadn’t committed any crime except that of being kids too young to take care of ourselves,” Maxey said.

The two boys stayed in juvie, as they called it, for the entire school year, which was sixth grade for Carl. They walked to Audubon Elementary School for classes, where they were quite a novelty. “I was always a hit at show-and-tell,” Carl once said, chuckling. “ ‘The juvenile delinquent . . . ’ ” Black kids were rare enough in this middle-class part of Spokane, not to mention black kids who made their home at the detention center. Possibly some parents whispered about the juvie kids and their imagined bad influence, but Burns remembered that Carl was well liked and got along with everybody, both students and teachers. Carl had already developed the beginnings of the charm that later disarmed many of his enemies. He also discovered that he had a gift for telling a story and for making a persuasive point in front of his sixth-grade peers. Maybe that was another thing that made him a hit at show-and-tell: his fledgling oratory skills.

Compared to the Spokane Children’s Home, juvie was easy to tolerate. Neither Maxey nor Burns had bad memories of it. Burns remembered it as “just another type of institution,” but at least one in which no cruelty was served along with the three square meals a day. For both Maxey and Burns, the manner of their leaving was the most memorable thing about juvie. According to Maxey, the county received deliveries of milk from an Indian mission boarding school, the Sacred Heart Mission, run by Jesuit fathers on the Coeur d’Alene Indian Reservation in DeSmet, Idaho, about fifty miles away. Sometimes, the priests themselves would bring the milk. On one of those deliveries, the head of the mission school, Father Cornelius E. Byrne, met the two black children. He saw two boys who needed a home.

“He said he’d take us both in if we wanted to come,” said Maxey. “I didn’t know anything about Catholicism. But he invited us down, and we took him up on it.” Ninon Schults recalled that “it was the port in the storm when there didn’t seem to be any.” The mission school was an unlikely port for a black child. Almost all of the students there were Indians of the Coeur d’Alene Tribe. A few white children had found their way there, too, but for the first time Maxey and Burns were in a place where the white children stood out more glaringly than the black children.

At first, Carl couldn’t believe what he found when he got to the reservation. “There were kids in his class who were in their twenties,” said Lou Maxey. “But they were all stunted physically and in such bad shape from chewing snoose [chewing tobacco], and from poor nutrition.” The reservation was a poverty-stricken place, with the disease and alcoholism endemic to many reservations of the time. Yet soon Maxey grew to love the people and the school, and he began to consider the mission school his first real home.

(Maxey would later credit Father Byrne with being the most influential person in his life.)

– – –

The civil rights movement was heating up in 1963 – even in the Northwest. Maxey had been an attorney for about 12 years when the following case landed in his lap:

One of his most prominent pro bono cases came in 1963, with an event that the Spokane newspapers labeled “The Haircut Uproar.” This incident seems mild compared to the news coming out of Alabama that spring and summer – massive civil rights demonstrations in Birmingham, hundreds of arrests, attack dogs tearing into lines of marchers, and fire hoses trained on children. Yet it sprang from the same impulse that was sweeping through much of America – an increasing conviction that it was time for segregation’s barriers to be toppled wherever they were found – even in a Spokane barber’s chair.

One October day, a Gonzaga University exchange student named Jangaba A. Johnson, a Fulbright scholar from Liberia, walked into John M. Wheeler’s downtown Spokane barbershop. There Johnson sat, waiting patiently for over an hour, until Wheeler finally came out of the back room and told Johnson to get out of the chair. Wheeler informed Johnson that he did not cut “colored hair.” Johnson walked out, embarrassed and hurt, and went to a black barbershop that the shoeshine man in the shop recommended. Johnson, the son of Liberia’s minister of culture, later said that in his country he had been “barbered by both colored and white shop owners and I assumed the same situation existed here.” Johnson went back to his Gonzaga dorm and told his fellow students what had happened. Dan O. Dugan, the prefect of Robinson Hall, said he could tell right away that Johnson was stung by the incident. Dugan and some other Gonzaga students, mostly white ones, decided that they had to do something about it. “We felt the best way to prevent recurrence of such a situation was to bring the matter to the attention of the residents of Spokane in an orderly fashion,” Dugan told reporters.

First, they wrote a letter of protest to the barber, signed by student body president John Villaume, asking for assurance that such an incident would not occur again. The barber gave them no such assurance. In fact, Wheeler was quoted in the paper later that week as saying, “I believe I have the right to accept or reject any person.” The seventy-six-year-old barber told a reporter that it had always been his policy “not to serve colored people, because you cannot mix trade in a barbershop and keep your customers.” He added that Johnson had been “very understanding and simply walked out.”

So the students organized a protest the next Saturday, October 19, 1963, outside of the barbershop. A total of thirty-five students, twenty-nine of them white, showed up with signs, one of which read, “Prejudice Prevents Progress: Help Spokane Grow.” Dugan and the students took great pains to avoid the appearance of provocation. Dugan said, “The whole thing was organized as a closely controlled demonstration with one purpose. We want to make our point and then we are finished. And we do not want to do anything that would reflect badly on the university.” Yet this small protest made big news, showing up on the national broadcast of the CBS News the next day. The Chicago Tribune ran the wire service story on its front page.

The students also contacted Maxey, who immediately went to work for Johnson. Maxey filed an official complaint with the Washington State Board Against Discrimination, which had been set up several years before. His argument was simple, the same one that was being used to open up lunch counters in Mississippi and Alabama: The law provides that places of “public resort and accommodation” may not refuse service because of race. A barbershop, he said, “clearly comes under that classification.”

Wheeler, however, proved unrepentant. “I have operated shops in Spokane for 45 years and it is my policy not to serve colored persons,” he told reporters. “This personal service is somewhat different than selling merchandise. I have refused to serve many people, including both white and Negro, but there has never been any trouble because of that policy.” Now he had all the trouble he could handle. The incident soon mushroomed into a rancorous political debate. A Spokane Republican state senator, A. O. Adams, defended Wheeler, announcing that he was certain that the citizens of Washington would never condone a situation that “takes away from majority groups their civil rights under the guise of protecting the civil rights of minority groups.” He also suggested that the barber might have somehow been the victim of “planned entrapment.” In other words, he suggested that Johnson was a plant, sent there strictly to cause trouble.

Maxey issued an outraged rebuttal. He said that Johnson was a “shy, sensitive student from Africa,” not a civil rights militant, and that “there is not the shadow of suggestion of entrapment in this case.” He accused the senator of disrupting the “very sanctity” of the upcoming hearing by issuing prejudicial public statements. Following Maxey’s complaint, the chief investigator of the State Board Against Discrimination arrived and tried one more time to get Wheeler to relent and sign a conciliatory letter saying that he would not discriminate in the future. Wheeler again refused. So, in November 1963, Wheeler was hauled before a meeting of the board’s tribunal. A crowd of three hundred people jammed the Spokane County Public Health Department auditorium. By this time the case was making not just national headlines, but, as Maxey commented in his remarks to the board, international headlines.

Maxey represented Johnson. Each side stipulated to the facts of the matter, which were that Johnson had walked in seeking a haircut and had sat in the chair for over an hour, until Wheeler finally came out and told him to leave. Nobody was going to argue that. The tribunal’s chairman tried to thin out the crowd by saying that the hearing would not include witness testimony and would consist strictly of dry legal arguments. “If you are expecting some kind of show,” said the chairman, “you might as well leave.” No one left, noted the Spokane Daily Chronicle.

The legal arguments weren’t so dry after all. Michael J. Hemovich, representing Wheeler, managed to come up with a novel argument: He maintained that forcing Wheeler to perform a personal service constituted “involuntary servitude.” Therefore, it violated the Thirteenth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution – the same amendment that abolished slavery in America. Maxey probably didn’t know whether to laugh or just shake his head. When his turn came, he scoffed at the very notion that Wheeler chose to “crown himself” with the protection of that particular amendment. Then, perhaps spurred to extra eloquence, he launched into his case.

“The eyes of the world are on Spokane and on a small barber shop,” he began. “But the issue is not small. We face the decision of whether a man with a public license can say on his own, ‘I cannot or I will not serve you.’ ” With a tone of controlled outrage, Maxey pointed out that this sort of behavior had been banned decades ago. In 1909, the state criminal code made it a misdemeanor to discriminate in public places. The position of the federal government was made clear in the Fourteenth Amendment, enacted after the Civil War and that proclaimed all citizens entitled to equal protection of the law. “Yet 100 years later,” he said, “we are arguing whether or not a Negro has the right to public accommodation.” Finally, Maxey noted that a barber’s license is a privilege, not a right. A barber cannot, under the law, arbitrarily refuse service to a customer because of his race.

The tribunal deliberated less than three minutes before ruling against Wheeler. Wheeler was ordered to cease refusing service because of race. He was ordered to write a letter to Johnson saying he would henceforth be served in his shop. And he was ordered to put up a poster for a year stating that all persons would be served “regardless of race, creed, color or national origin.” Wheeler refused once again to comply. He immediately appealed the ruling, saying he would seek to overturn the state’s public accommodations law. Two years later, a superior court judge upheld the board’s ruling, writing that a barber who opens a shop “thereby invites every orderly and well-behaved person” into his place of business for service. “The statute will not permit him to say, ‘You are a slave or the son of a slave; therefore I will not shave you,’ ” said the judge. The judge who issued this ruling was William H. “Bill” Williams, Maxey’s closest friend from law school.

Wheeler still wasn’t finished. He eventually took his appeal all the way to the Washington State Supreme Court. In May of 1967, the justices ruled 9–0 against him and termed his arguments “without merit.” Wheeler, stubborn to the end, never did comply with the ruling. He chose to retire instead.

– – –

In 1968, Maxey was an outspoken opponent of the Vietnam War. He had recently made a speech at his alma mater, Gonzaga University, urging students to speak out against injustice and not to be “chicken”:

One Gonzaga student certainly chose not to be “chicken” that October. The occasion was the campaign visit to Spokane of Governor Spiro T. Agnew of Maryland, Nixon’s running mate. Spokane, which now had a city population of about 188,500 and a metro area of about 276,000, was never blasé about the visit of any national candidate. And since conservative Spokane tended to lean Republican, Agnew’s speech became a downtown-clogging event, drawing a crowd estimated at 2,000 to the Parkade Plaza, a brick-paved courtyard lined with stores and balconies. Agnew paraded into the city with a small motorcade and was ushered to a platform set up near the plaza’s fountain. Hundreds of balloons soared into the blue sky. Reporters were told that he would deliver one of his standard campaign policy speeches, about natural resources. Yet circumstances soon pointed Agnew in a different direction. As Agnew launched into his speech, a group of Gonzaga students carrying Humphrey signs began chanting, “We want Humphrey! We want Humphrey!”

Agnew, well seasoned in dealing with disruptions, smoothly switched to the topic of dissent in democracies: “Dissent is proper in this democracy. But when dissent prohibits others from being heard it is not the type of dissent we need. This type of dissent which is evident here does nothing but lead to anarchy and frustration.” Warming to this new theme, Agnew said he believed in voting rights for eighteen-year-olds (the limit was twenty-one at the time), and he advocated an “intern system” in government so that youth could learn how government really worked. “Many young people, however, say they cannot participate in government and in politics,” Agnew continued. “I say to you, they can if they just go to work within the framework of the two major political parties. The Republican Party welcomes them if they just quit crying and start working. This will accomplish more than just carrying obscene signs down the street.”

This kind of talk played well with the crowd. The Chronicle reported that the hecklers “failed to disturb his aplomb.” Agnew then contrasted the protesters with a young group of his supporters in the audience, described by veteran Chronicle political writer John J. Lemon as “a group of smartly clad young women in white blouses, skimmer hats and Nixon-Agnew ribbons.” Agnew proclaimed that “despite voices of dissent from a few, this generation has produced the finest group of young people we have ever had in this country.”

After that he switched to an attack on the third-party platform of George Wallace and Curtis LeMay, which he said “bristles with increased iron-jawed defiance of good judgment.” He accused them of irresponsible talk about the use of nuclear arms. “The United States has never been a saber-rattling nation,” said Agnew. “I want to remind you that, [when the United States had] the only nuclear capacity in the world, we could have conquered the world, and for those who called us imperialists, look at our conduct.” At this point, a voice from a balcony above the platform shouted clearly, “Warmonger!” Agnew stopped his speech and looked around. “Who said that?” A young man described by Lemon as a “dark, longhaired youth” grasped the balcony railing and shouted, “I said it.” Then he flashed the V-for peace symbol and said, “What the hell do you think this means?”

Some people in the crowd shouted, “Get him!” Others began to boo as two bystanders attempted to yank the young man forcibly from the railing. A Spokane police officer, already on the balcony, grabbed him and pulled him away. The officer told the young man he was under arrest and began to hustle him off the balcony. Agnew looked up at the commotion, which had lasted less than fifteen seconds, and said, “Well, it’s really tragic to think that somewhere, somebody in that young man’s life has failed him.” The crowd responded with applause and boos.

That young man was Peter Jerome McDonough, a twenty-year-old Gonzaga University senior from Sacramento, California. As the officer led him away, Secret Service agents converged and led him into an office next to the plaza. They searched and questioned him. Then they drove him to the police station and booked him for disorderly conduct, with bail set at twenty-five dollars. Fellow Gonzaga students threw some money together and bailed McDonough out right away. Maxey was right there, offering his services pro bono. To Maxey, the arrest was a clear violation of free-speech rights. He told reporters, “We do not believe this young man should be arrested or incarcerated because of a simple exercise of free speech.”

At his municipal court hearing a few days later, McDonough told Justice of the Peace Ellsworth Gump, “I didn’t go there to embarrass or insult the candidate. I didn’t agree with him and thought it was my place to say something, so I did. I am concerned about the country and our involvement in Vietnam. I think it is wrong to be there.” A group of Gonzaga students were in the courtroom to support him. Film footage of the incident was shown, and when Agnew was shown saying “somewhere, somebody in that young man’s life has failed him,” the students began loudly laughing and clapping. Gump ordered the courtroom cleared, declaring that if people were allowed to express approval or disapproval in a courtroom, any court would descend into “complete chaos,” a remark that would come to bear on another Maxey case two years later. Gump relented soon afterward and allowed the students back in.

In McDonough’s defense, Maxey argued that the student had simply exercised his right of free speech in a public forum and had not been “riotous” or unduly disruptive. Maxey also presented a petition from 465 Gonzaga students and faculty members attesting to McDonough’s good character. Maxey then moved for dismissal. Gump was not swayed. He denied Maxey’s motion and found McDonough guilty. “The peace and good order of the community has been offended by your words and actions,” ruled Gump. “The way things are going, we are in a tough position as to what can be done to keep order. We all have the right to speech and dissent, but there is an orderly way to do it or we will end up in shambles. Perhaps the $100 fine is sufficient to deter others from doing the same.”

Less than a week later, Maxey filed an appeal to the superior court, which was heard in January of 1969, right after Agnew was sworn in as the new vice president. At this second nonjury trial, McDonough delivered what the Chronicle called “an intense recital of his views against what he called ‘an immoral war.’ ” He also said he believed that shouting a protest at politically rally “is as American as anything.” Judge Ross R. Rakow was not inclined to rule on how “American” it was. He said at the beginning that he had narrowed the issue strictly to whether McDonough was in fact guilty of disorderly conduct by interrupting the speaker. So Maxey’s strategy was to assert that it was already a raucous event, with dozens of Humphrey backers jeering throughout the speech. None of them were arrested for disorderly conduct; McDonough shouldn’t have been either.

It didn’t work. Rakow ruled that “no man may exercise his rights at an unreasonable expense to others” and upheld the conviction and hundred-dollar fine. Maxey immediately announced he would appeal the case to the state supreme court. It took more than a year for the case to make it into the court’s docket. By then, May 1970, the arguments of Maxey and his law partner Gordon Bovey were three-pronged: (1) The city’s disorderly conduct ordinance was unconstitutionally vague, (2) McDonough’s free-speech rights were abridged, and (3) shouting one word was hardly being “disorderly.”

As it turned out, only the last argument was necessary. On May 26, 1971, the justices ruled in favor of Maxey and McDonough and reversed the conviction. Justice Hugh J. Rosellini (no direct relationship to the former governor) noted in his majority opinion that the “political rally was a noisy and partisan event … Shouting the word ‘warmonger’ but once – without more to indicate a further purpose or intention of breaking up the meeting, or to deprive the speaker of his audience, or to interfere with the rights of others to hear, or the speaker to speak – did not amount to a disturbance of the peace, in fact or in law.” Three other judges joined the five-judge majority, but they wrote a separate opinion stating that the city’s law was constitutional.

McDonough was far out of earshot when the ruling was announced. He was in the middle of a two-year stint as a teacher at the Mpima Seminary in Kabwe, Zambia. He had lost his student draft deferment upon graduating from Gonzaga, and as he explained in a December of 1969 letter to Maxey from Zambia, the draft board gave him two choices: “They told me I could either go to Africa as a II-A [deferred because of occupation] or stay at home as a C.O. [conscientious objector]

… So I figured that teaching school would be a bigger help than dumping bedpans in some hospital.” Maxey wrote back, gave him an update on his appeal, and also gave him an update on Agnew. “The more we see and read of Agnew, the more your comment becomes appropriate,” wrote Maxey in late 1969. “Isn’t it idiotic that you should be arrested for calling a warmonger a warmonger? Agnew should have been in jail four or five times over.”

As it turned out, Agnew avoided jail, but just barely. In 1973, he reached a plea agreement with the U.S. Justice Department on charges of income tax evasion and money laundering. He resigned the vice presidency and pleaded nolo contendere (no contest) to a single charge of tax evasion. He was fined ten thousand dollars and sentenced to three years of probation. Agnew’s political career ended in disgrace. Perhaps somewhere, somebody in Agnew’s life had failed him.