Medical Lake’s ‘castle’ built by English lord

MEDICAL LAKE – The quiet little burg of Medical Lake isn’t the sort of place you’d expect to find a castle built by an English lord.

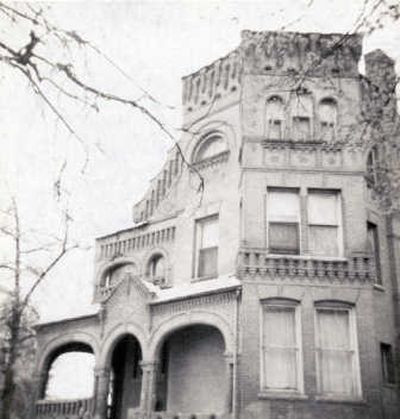

A sleepy main drag, with its dusty taverns and pickup trucks, is more Wild West than West End, but on the 600 block of Lake Street sits the quirky brick structure known to locals as the Hallett House. Its namesake, Stanley Hallett, dropped the title of “lord” when he landed in America, but in Eastern Washington, royalty is recognized wherever it’s found.

While some might not call it a castle, the Hallett House certainly isn’t your typical turn-of-the-century mansion. When it entered The National Register of Historic Places in 1976, it was described as “a genuine architectural oddity” that “could only have been built by a joker or a madman.” But while Hallett may have had a lighter side, the only madness in him was perhaps an excess of ambition common to many of his time.

Born in 1851 near Surrey, England, Hallett attended Packing College, where he achieved high marks and earned a silver medal as reward of merit. The esteemed young lad, like so many others of that era, was driven by a spirit of adventure that led him first to the West Indies, then America.

Hallett traveled to San Francisco in 1872, where for a few years he tried his hand at business and ranching with moderate success. Too young to be sedentary for long, he set out for the small village of Spokane Falls, which his cousin assured him was a sight to behold.

He drove a light rig north, traveling mainly by night to avoid notice by warring tribesmen, but when he finally arrived in 1877 the place was, in his estimation, “nothing but a rock pile.” He turned around and went west to “Lac de Medicine,” as French Canadian pioneer Andrew Lefevre had dubbed his fledgling settlement.

The lake had long been known by Spokane and Colville Indians as “skookum limechin chuch,” or strong medicine water, because of its healing characteristics. Sniffing a business opportunity, Hallett immediately set about acquiring a large swath of land in order to get in early on a good thing. The hunch paid off when much of his original homestead became the town itself after its incorporation years later.

Soon after he came on the scene, Hallett landed his first leading role when possible tribal uprisings began to worry the neighborhood. He organized a group of 100 volunteers to defend the town which, after the danger had passed, earned him both the respect of his neighbors and a commission as first lieutenant in the U.S. Army.

Talk of the lake’s extraordinary healing powers started to spread through word-of-mouth and national news briefs. One, from the August 1879 West Shore Magazine of Portland, whimsically gushed, “The curative properties are said to be marvelous. It will cure almost any disease, except lying and poverty.”

Visitors flocked and Hallett rode high the wave of interest in his little town. According to Jonathan Edwards’ “History of Spokane County,” Hallett was one of the first entrepreneurs to bottle the lake’s minerals for profitable worldwide sale.

With budding business success, Hallett must have determined he was ripe for marriage. He traveled back to England in 1880 to wed his childhood sweetheart, Margaret Orion, who lived with him in Medical Lake for eight years before her death. He returned to England a year later to marry his wife’s sister, Emily.

Throughout this period Hallett’s political career had begun taking shape. He was elected as a Spokane county commissioner in 1884 then as territorial commissioner in 1888, when he oversaw construction of the Eastern Washington Hospital for the Insane (later renamed Eastern State Hospital). Once the city became incorporated in 1890, he grabbed the distinction of being its first mayor. After this he went on to serve a term in the State Senate and eight consecutive years as town treasurer.

By 1900, at the age of 49, Hallett’s boundless ambition at last seemed to wane. He settled down to begin work on his castle, a fanciful structure his neighbors described as “only fitting for an English family.”

Hallett designed the three-story house himself and took evident pride in making it a peculiarly distinctive architectural display. A veranda with arched openings wraps the west and south of the house, and an observation tower caps the structure like a grand tiara. Visitors to Medical Lake, in fact, would often assemble on the southeast corner opposite the house to remark on how closely the tower resembles the English crown.

The most extraordinary feature of the house, however, is the exterior brickwork. The bricks were made at Hangman Creek and carted to the site by wagon. Once the rest of the house was nearly finished, the bricks were chiseled into a variety of geometric shapes, a process that gave the facade a rocky, dreamlike appearance.

The house took nearly three years to complete. The tedious work was carried out by a family named Cook, also English, who lived in one of Hallett’s 12 houses rent-free all the while.

While his house was being refined, Hallett was busy watering trees. He was an arborist at heart who planted the first trees on Lake Street as well as the maples, chestnuts and elms in many neighbor’s yards, even taking the time to water them when no one else would. He was also known to do maintenance work for widows of the town, hiring others to help when he wasn’t available.

Once it was finished, the house quickly became known as a hub of activity. Every Fourth of July, half the town would gather on the front lawn as Hallett and his children would shower them all with fireworks from atop the tower.

A 1972 Medical Lake centennial issue of the Cheney Free Press speaks of those halcyon days as seen through the eyes of one of Hallett’s four children, daughter George (Maude) Ross. She says the grand piano was so big it had to be hoisted up to the third floor ballroom via the stairwell before stairs were built. When it was taken out years later, it had to be lowered from a window.

Ross spoke fondly of weekend revelry when dancers would pack the house until early morning. The ballroom even had a kitchenette so guests never had to leave the room for refreshments.

“Father loved company,” Ross said, “and we never knew if there would be an extra 20 for dinner.”

The children eventually moved away, but Hallett remained in the house until his death from cancer in 1926 at the age of 75. In 1943, the federal government leased the house from his widow, Emily, and divided it into 11 apartments for war workers’ housing.

It’s changed hands several times since then, and out-of-state investors now rent the apartments to local tenants. A “For Rent” sign is planted in the front yard where Hallett once planted trees. Most of the house’s original interior has been wiped away, and much of the decorative exterior brick work has crumbled, but if a visitor walks to the southeast corner of Lake and Stanley streets, the castle’s “crown” can still be seen, a stone-cast testimony to the lord of Medical Lake.