Priest toiled for civil rights

Being black and Roman Catholic may be common in New Orleans, but it remains rare in Spokane.

The Diocese of Spokane has ordained only one black priest.

In researching African American Catholics for his doctoral dissertation in leadership studies at Gonzaga University, Bob Bartlett discovered that most stories of black Catholics remain untold.

That invisibility affects students he has worked with for 18 years as director of Unity House, Gonzaga University’s multicultural center.

It also has made it hard for him to find a place to tell the story of John Hopkins, the only African American ordained as a priest in the Diocese of Spokane.

“For people on the margins, the difficulty of telling stories is a constant reminder of trying to drive a square peg into a round hole,” Bartlett says.

However, he adds, “When we tell stories of people, we can learn from their lives. There’s value in ‘counter storytelling,’ sharing about the lives of people not included in the dominant narrative, people who can teach us who we are.”

Through his research, Bartlett found stories about black theologians, bishops, priests and nuns who worked for civil rights in the 1960s. One of those was Hopkins.

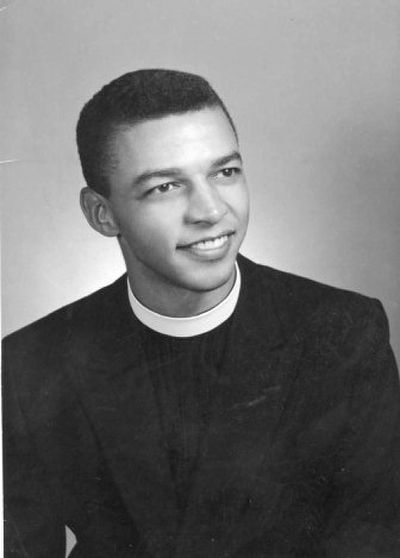

Born in Missoula, Hopkins moved to Spokane as a child. He graduated from Gonzaga Prep, where he was student body president, a member of the debate team and the class valedictorian.

He went on to receive bachelor’s and master’s degrees in philosophy from GU, then completed a four-year course in theology at St. Bernard’s Seminary in Dubuque, Iowa.

In June 1961, Hopkins was ordained at the Cathedral of Our Lady of Lourdes in Spokane. He celebrated his first Mass at his home parish, St. Ann’s Catholic Church, which also is Bartlett’s parish.

Hopkins served as assistant pastor at Our Lady of Fatima and at St. Anthony’s in Spokane before leaving the ministry to pursue a career in social, political and legal affairs.

During the 1960s, he helped form a Spokane interracial council, drawing together religious, lay, business and civic leaders to challenge racial bigotry in the city.

After leaving Spokane, Hopkins became the first black person to earn a doctor of philosophy degree at Columbia University, in 1976. He then earned a doctorate in education from the Teachers College at Columbia.

He taught both at the Bishop White Seminary at GU and at the historically black Howard University in Washington, D.C.

Among Hopkins’ accomplishments:

“He wrote two books: “Racism: A Philosophical Perspective” and “The Continuing Mis-education of African American Youth.”

“He served on a team of 25 people responsible for negotiating and overseeing the implementation of sections of the 1964 Civil Rights Act that called for the elimination of segregation.

“He worked as a research associate at Columbia University’s Institute on International Change and conducted an extended study of interracial and multinational cooperation and conflict in South Africa.

In 1989, Hopkins died in Washington, D.C., at the age of 59. His memorial Mass was at Our Lady of Lourdes.

“While Father John’s life and works as Spokane’s first black Catholic shepherd lies in obscurity, his story cries to be heard,” Bartlett says. “His life, lived with a passion for justice as a black man in an overwhelmingly white place, exemplifies both speaking his truth and offering alternative ideas to the community and world.”

In his research, Bartlett found other overlooked information.

“Few know there have been 700 black saints, that there were black Popes from Africa, that Africans were Catholic before slavery or that there were black Catholics in the United States before the Irish and Italian immigrations,” Bartlett says.

He learned of black Catholic churches in Houston, Milwaukee and Dayton, Ohio, some of which have paintings of Jesus, Joseph, Mary, the wise men and stations-of-the-cross figures as black people.

Bartlett, who receives his doctoral degree today and plans to teach, says he wrote about Hopkins and other black Catholics as a way to make the invisible visible, the unknown known, the voiceless have voice.

“How can we inspire black Catholics to become priests if we do not know of any?” he asks. “How can we convince blacks to remain Catholic if we hide the history of black Catholics in this country?”