PEST DETECTIVE

When Rod Schneidmiller started Sterling International 25 years ago, he told would-be customers that his Spokane company had created a safer way to trap and kill bugs, without insecticides.

Back then the standard reply he heard was, “Why shouldn’t I just spray them with poison? The only good bug is a dead bug.”

More often than not, they regarded Schneidmiller as odd for selling something that didn’t use carpet-bombing insecticide.

This past week, the Spokane Valley company celebrated its 25th anniversary. It survived, Schneidmiller said, because what was once considered odd is now widely seen as a safer, smarter and environmentally friendly way to eradicate pest insects.

“We were a little ahead of the curve,” he said. But, he added, “You don’t want to be too far ahead of the curve that people aren’t ready for what you have to offer.”

Its breakthrough product was a reusable yellowjacket trap, a yellow-green plastic cone about 10 inches tall that attracts the bugs inside but doesn’t let them out. Once the trap fills up, consumers take off the top, dump out the bugs and refill the cartridge with a chemical lure developed inside Sterling’s lab.

The yellowjacket trap has sold millions and has become a backyard fixture like hibachis and garden hoses across North America and parts of Europe.

Not bad for a company that in 1982 began selling flytraps for about $4 apiece.

Today Sterling has annual revenues from $15 million to $20 million — according to outside analysts. Schneidmiller won’t discuss company sales figures for the company he and his wife, Georgette, own. The 60-worker company adds dozens of seasonal workers in the spring to handle production needed to ship products across the nation and overseas.

That heavy spring rush started earlier this year, due to warm weather in the South. “We expected to shut down our second shift last week. But we’re still going with two shifts for as long as the demand continues,” Schneidmiller said.

The total U.S. market for bug removal or control continues to grow. U.S. sales during 2005 for all retail pest control products came to $2.5 billion. Much of that growth is occurring in warmer states and in fast-growing areas of the country, like the Southwest, Florida and Texas.

Schneidmiller says he’s a private person not prone to discuss his company at length. “The reason this company was successful is the group of people who are here; they’ve made it happen,” he said. For years he declined to be interviewed by Spokane media and has agreed to talk because the company is marking its 25th anniversary.

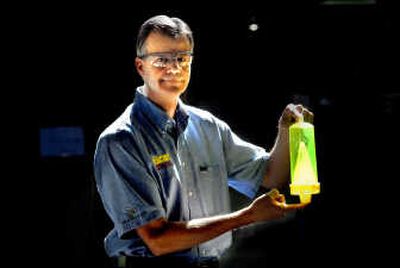

During a recent tour of Sterling’s 110,000-square-foot building at the Spokane Industrial Park, Schneidmiller starts with a visit to the company’s director of research, Qing-He Zhang. Zhang uses advanced technology that is attached to test-insect antennas and checks the electrical response to different chemicals. Because the goal is to attract insects, the chemicals Sterling use all occur naturally. They fall into groups that are either food or sex attractants, Zhang said.

“We’re a tech company, but you just can’t see it,” Schneidmiller said. The company holds several patents, both for the chemical formulations used inside the traps, known as attractants, and for the trap design.

Zhang spends most of his time helping Sterling prepare for its next probable insect targets — paper wasps and mosquitoes.

That work involves testing various naturally occurring substances and spending months hunting for the very specific chemical compounds that are most effective at attracting an insect species. Once the right combination is identified, Sterling finds a way to synthesize that natural compound in a form that can be stored and used easily inside the company’s traps.

Up to now, Sterling has relied on products that attract pests. The company is considering adding a line of repellents as well, according to Schneidmiller.

Schneidmiller, who’s 51, got into this line of work after earning an agronomy degree from Washington State University. Having been raised on a grass seed farm in the Spokane Valley, he followed a hunch that money could be made developing less toxic traps for the area’s most common bugs.

He built his bug-trap prototypes in his garage. When he took them to area retailers, Schneidmiller tried to explain that sprays killed not just the flies or yellowjackets but many other bugs that played a role in maintaining healthy plant life.

In 1987, the company switched its brand name to RESCUE, which is the identifier most consumers remember when buying Sterling’s products.

At that point, Sterling was selling its products mostly to state and Northwest retailers, working out of a converted warehouse in Spokane Valley. One Thursday afternoon, Schneidmiller got a phone call from a distributor asking if he could deliver an order of yellowjacket traps to the Portland area. The order was based on getting the product there in 24 hours.

“We didn’t have a lot of inventory then waiting around. But we decided to bust our butts. Everyone stayed on and we told the freight people to wait a little longer,” said Schneidmiller.

That customer was Bi-Mart, one of Oregon’s larger chain-store retailers. “We got that order to them the next day and they’ve been a customer ever since,” Schneidmiller said.

Since the 1990s, Sterling has taken advantage of distributors to get its products into some of the nation’s largest retailers. Its traps are carried by Wal-Mart, Lowe’s, Home Depot, Ace Hardware and True Value.

Sterling doesn’t set the retail price. “You will find the yellowjacket traps in the $10 range” no matter where you look, said Schneidmiller.

This time of year the RESCUE products take up shelf space or occupy sizable sections of the stores’ garden displays. Schneidmiller admits he walks through area stores to see how they’re selling and how they’re displayed.

“Every one of us here is guilty of adjusting and rearranging our products inside some stores when we go into them.

“If I’m in a store, I do it every time,” Schneidmiller said, laughing like a teen who’s pranked a pal.

Sterling clearly saw the advantages of nontoxic bug traps before many others did, said Pat Cotts, technical services manager for the western region of Orkin, a corporate service provider of pest control management for commercial customers such as resorts or golf courses.

“Their products do the job. We choose them for some of our clients when it’s appropriate,” Cotts said. At the same time, he said, research on bug attractants continues to evolve. Cotts said Orkin and the University of California are working together on a yellowjacket trap that, in his view, would do a better job than the RESCUE version.

Schneidmiller says Sterling is watching what the competitors are up to, as well. But being small gives his firm some advantages over large competitors such as SC Johnson and Ortho, which are trying to take a larger bite of the insect-eradication niche.

“We focus on what we do and we do it well, based on our research and development. Most big companies in this business are mostly marketing. They slap their name on a product and expect it to sell. And that doesn’t happen,” he said.

The innovation principle took hold of Schneidmiller this past year, prompting Sterling to develop a reusable flytrap that uses recycled two-liter plastic bottles. After testing the idea, Sterling will launch the product next spring, calling it the Pop Fly Trap.

Instead of buying new containers, Sterling is asking area schools and others to sell the company recycled pop bottles. Sterling will pay 10 cents for every bottle that is cleaned and has the label removed. Information on how the recycling program works is at the company’s Web site at www.rescue.com.

Schneidmiller was the driving force behind the development of that idea, which Wal-Mart has said it will begin selling in 2008.

“But I don’t want to say what I did,” Schneidmiller noted. “This was a team effort. It’s something we all worked on here.”