FACE OF STONE

The most dramatic feature in the climbing mecca of Oregon’s Smith Rock State Park is Monkey Face, a 350-foot formation revered by tourists and climbers alike.

Sightseers viewing from the south note the uncanny profile of a monkey at the pinnacle. Climbers note the myriad routes with overhangs and long drops on which they can test their mettle, and the nearly 200-foot rappel into space that awaits them at the top.

“Exposure in the mouth is big,” said Mike Volk, a longtime climber at the Smith Rock. “Coming out of the mouth is called Panic Point. You’re looking straight down at the ground, with no rock below you.”

The usual approach to Monkey Face is a switchback path over Misery Ridge. Monkey Face can be seen while driving through Terrebonne, Ore., toward Smith Rock, but from the park, the pinnacle is blocked from view by other rock walls.

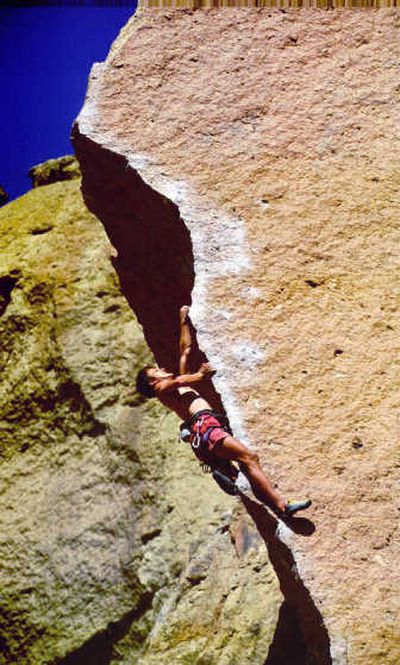

In the northwest corner of the park, Monkey Face rises from the Crooked River. Its compressed volcanic ash, known as welded tuff, is white near the rock’s base and reddish higher up. Nearly all of Monkey Face is either vertical or overhanging on all sides.

“Most sport climbers aren’t used to that kind of exposure,” Volk said while hiking along Misery Ridge. Volk operates a Web site about the park out of his home near Smith Rock State Park.

The first recorded ascent of Monkey Face was made on Jan. 1, 1960, by two men and a woman up what is now called the Pioneer Route.

That route, up the east and south sides of the spire, is now considered easy by most advanced climbers. Since 1960, 37 additional routes have been established on Monkey Face, along with 24 variations of those routes, according to Bend’s Alan Watts, author of “Climber’s Guide to Smith Rock.”

Watts, a pioneer of sport climbing at Smith Rock in the 1980s, established many of those routes and was the first person to free climb several other routes on Monkey Face and throughout the park. A free climb is an ascent with protective gear, but no reliance on it to progress up the rock.

“There’s nothing quite like it,” Watts said of Monkey Face. “Not just at Smith Rock, but just about anywhere. No matter which way you climb, everything is overhung. It makes for pretty hard climbing.”

Many of the climbing routes on Monkey Face are aid routes, meaning that to safely ascend, climbers must place gear in the rock as they climb. But several are sport-climbing routes, on which climbers clip into bolts that have already been fixed onto the rock by other climbers. Smith Rock is renowned for its sport-climbing opportunities.

In 1989, Watts bolted the Just Do It route while being filmed with other climbers for NBC’s “Sportsworld.” None of the climbers then could finish the route without relying on their safety gear, but Jean-Baptiste Tribout of France accomplished that feat in 1992.

At the time, Just Do It was considered the most difficult sport-climbing route in the United States, according to Watts. Other, more challenging climbs were discovered in the late ‘90s, but the route remains one of the most arduous in the country.

Just Do It runs up the middle of the smooth east face of Monkey Face. The bolts on the route can be seen shining in the sun from the top of Misery Ridge. The climb is straight up.

Redmond’s Ian Caldwell, one of the top climbers in Oregon, according to Volk and Watts, has worked on climbing Just Do It, which has been free-climbed by a handful of climbers since 1992.

“It’s always been a dream of mine, when I first started rock climbing, which was right about the time Tribout did it,” Caldwell said. “It’ll happen someday.”

Caldwell — who is currently working on an even harder route at Smith Rock called Shock and Awe — has reached the top of Monkey Face on the Pioneer Route. He compares standing on top of the spire to standing on top of a ball.

“The rock rolls down all sides,” Caldwell explained. “It’s an exposed feeling, but a sense of accomplishment. You’re at this point that’s really hard to get to.”

Carol Simpson, who owns First Ascent Climbing Services in Terrebonne, used to guide climbers up the Pioneer Route of Monkey Face.

“I was guiding once, and it took a woman 30 minutes to step out onto Panic Point,” Simpson said. “There’s a reason they call it Panic Point.

“Something like Monkey Face, that’s multipitch, you get a huge surge of excitement and adrenaline. Moves are always scarier when you’re that high up.”

Multi-pitch climbs are too long for a single belay rope. And then there’s the rappel.

Most climbers are accustomed to rappelling along a rock wall. But because of the overhanging nature of Monkey Face, and the typically strong wind in the area, rappelling off the spire thrusts climbers into the open air.

“When you start rappelling, you’re off in space,” Caldwell said.

Watts writes in his “Climber’s Guide to Smith Rock” about the climbing feats — and other happenings of note — on Monkey Face, mostly from the 1980s:

“The dramatic setting makes Monkey Face the place of choice for kooks seeking an adrenaline rush. A solo ascent (no rope) of the Pioneer Route from the ground in nine minutes, weddings on the summit … The best non-climbing effort came when Adam Grosowsky strung a tight wire between the Springboard and the Monkey’s mouth. After several rehearsals he walked across the span without a safety line. Witnesses reported that the solo walk was shaky and agonizing to watch — he nearly took a dive and never repeated the feat.”

More recently, climbers have “slack-lined” across the expanse from Springboard — a rock ledge located about 20 feet across from Monkey Face — to the Monkey’s mouth. In slack lining, climbers walk across a rope while strapped into a harness that is attached to the rope.

But most come to Smith Rock to climb or hike. And no matter what their goal, they will feel the pull of the primate.

Said Volk: “If you come to Smith Rock to climb, you’ll at least want to go look at Monkey Face to see what it’s all about.”