Flag from a father

A chance conversation in a Spokane health club last fall has reunited a family some 5,000 miles away with a precious heirloom from a husband and father gone for 66 years.

Depending on one’s view, it took a miracle or a series of bizarre coincidences to allow Duane Costa of Spokane to give the Kodama family of Niigata, Japan, something so stunningly rare they couldn’t even dream it existed.

It seemed impossible that the flag Heitaro Kodama carried with him to war in 1941 would come back, his widow Katsue Kodama said.

“I’m overwhelmed with all the feelings,” the 89-year-old great-grandmother said recently in an interview with The Spokesman- Review.

The flag had been in Spokane since 1945, when Marine commando Jerry Costa returned from the South Pacific. After Jerry died in 2000, his brother Duane inherited the flag with Jerry’s other possessions.

Duane Costa, who only hoped to find out more about the flag and preserve it when he first brought it to the Japanese Cultural Center at Mukogawa Fort Wright Institute, is equally overwhelmed that it was returned to its rightful owners.

“This is a miracle, that she’s able to feel that flag in her hands,” Duane Costa said. “It’s where it belongs. It was meant to be.”

But sometimes, even miracles need helpers. Forging the link between Spokane and Niigata, a city of some 800,000 on the northwest coast of Honshu island, were students and staff from Mukogawa in Spokane and their main university in Nishinomiya, and the Japanese news media.

A soldier’s tale

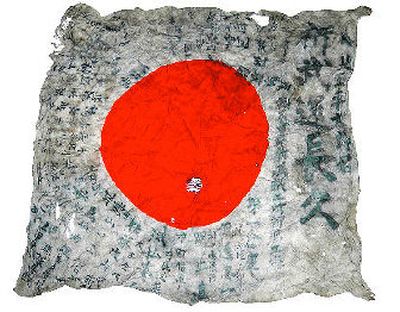

Heitaro Kodama was working at the Niigata Steel Works warehouse in early 1941 when he was drafted by the Japanese army. His country had been at war on the Asian continent since 1937. As is customary in Japan, his family, friends and co-workers presented Kodama with the nation’s flag – a red sun in the middle of a white field. After writing his name in large script, some 40 of them signed it with their wishes for his good fortune and safe return.

Japanese soldiers would often wear such flags under their uniforms, a string attached to one end tied around their necks.Just months before Heitaro was drafted, he had married Katsue Kanda. When she walked him to the Niigata train station to see him off in the spring of 1941, Katsue was pregnant. If the baby is a boy, he asked her, please call him Toshiaki, a name which translates into bright and skillful.

She moved into her parent’s home to await his return.

After the attack on Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941, Japan was also at war with the United States and its allies in the Pacific. One week later, Toshiaki was born. In those days, Japanese soldiers weren’t allowed family visits, and Heitaro never saw his son.

But he wrote home frequently. “I think he wrote 50 to 100 cards and letters to my mother while he was on duty,” Toshiaki Kodama said recently. One of the letters coming back to Heitaro told him of his son’s birth.

The letters continued even after Cpl. Heitaro Kodama and his unit, the 16th Infantry Regiment, 2nd Division, sailed for the southern territories occupied by the Japanese army, which by May 1942 stretched as far as Guadalcanal in the Solomon Islands.

A Marine’s tale

Silvio “Jerry” Costa was a proud and enthusiastic Marine. Born and raised in Clayton, Wash., he left high school at 17 and enlisted in August 1941, before the United States was at war. After Pearl Harbor, he was part of an elite commando unit, the 2nd Raider Battalion, also known as Carlson’s Raiders, where he rose to the rank of sergeant.

He scratched his name, unit and its slogan “Gung Ho” on a small square of aluminum, along with the names of the island battles he participated in: Makin, Midway, Guadalcanal, Bougainville, Tulagi, Iwo Jima.

Jerry Costa talked little about the horror of those battles when he returned from the Pacific, his brother Duane said. He did talk about landing and leaving Makin Atoll by submarine in August 1942, and marked where he stood in a photo of Marines on the sub’s deck.

In November 1942, Carlson’s Raiders were sent to Guadalcanal, where the American, British and Australian forces had been fighting the Japanese army for control of the jungle island and its strategic air field for more than three months. The raiders spent more than a month behind Japanese lines in a guerrilla campaign, an event that later came to be known as “the Long Patrol.”

By the time the Japanese Army left Guadalcanal in February 1943, they had lost an estimated 23,000 soldiers from the battle and disease, U.S. military sources estimate. The Americans lost about 1,600 ground troops. Instead of advancing south, the Japanese army would spend the next 2½ years pulling back toward the mainland.

Cpl. Kodama never came home from Guadalcanal. His family received word from the government that he was killed on the northern part of the island on Jan. 8, 1943. The body could not be shipped home. The government sent a small amount of sand from the island for the family.

Sgt. Costa survived Guadalcanal and three other battles, returning to Spokane in 1945.

Change of heart

Duane Costa remembers first seeing the Japanese flag with strange writing on it when Jerry, who was 11 years older, came home from the war. Jerry said very little about it, other than a dead soldier on an island had been wearing it.

Jerry never said what island, or whether he killed the owner of the flag or someone else did. That wasn’t unusual, because even though he was proud of serving in the Marines, Jerry hardly talked about the war.

The flag has a large hole, probably from a bullet, and a stain, possibly blood. Jerry Costa folded it and placed it in a scrapbook of Spokesman-Review and Chronicle clippings about the war and the Corps. About the only time it came out was when it was set aside while people looked through the scrapbook.

Jerry Costa became a truck driver for local soft-drink and beer distributors, and a Teamster. He never married, and, said Duane, “in later years he struggled with alcohol.”

For a while he lived with Duane and his family. Later he lived in a small house on East Pacific.

For some years after the war, Jerry carried a lot of anger and bitterness toward the Japanese, Duane Costa said. But later in life, he came to know and respect a Japanese woman who lived a few doors down. He met her family and the more he learned, the more he came to like and respect the country and its people.

“He died loving the Japanese people,” Duane Costa said.

When Jerry died, he left everything to Duane – including the flag with the Japanese writing, the hole and the possible blood stain.

Difficult times

After Heitaro Kodama died in the war, Katsue struggled to make ends meet while raising a son and working as a day laborer. Heitaro’s body was never shipped home, but she and Toshiaki had the letters he wrote, plus some other personal things including a lock of hair, his military medals and some clothes he wore.

All of that was destroyed in 1964 when an earthquake struck Niigata and caused a massive fire at a local oil refinery. The home where they lived was one of many engulfed in the fire.

After the quake, Katsue and Toshiaki moved around, living in other people’s homes and quake-relief emergency housing until Katsue was able to buy a small, hilly piece of property through a military pension mortgage fund. She continued to work as a day laborer while leveling the land herself with a spade, for a family home.

“It was tough. I was alone,” she recalled recently. “We have survived more hardship than most others. I am glad that I have been allowed to live through many difficult times.”

In 1999, Toshiaki joined about a dozen families of other Japanese soldiers who died in the fighting at Guadalcanal for a pilgrimage to the island. He had been told where on the island his father was reported to have died, but wasn’t allowed to go to that remote area because of tribal unrest.

“I had to give up the hope to pick up my father’s bones and ashes,” Toshiaki said. Instead, he brought back some sand and pieces of discolored coral that reminded him of bones, which he found near a memorial tower to all soldiers killed on the island.

The bottle with sand and coral joined a photo of Heitaro that a relative gave them after the fire for the memorial to his father on the butsudan, or Buddhist altar, in the Kodama family home.

Educational project

Duane Costa didn’t know what to do with the flag he inherited from his brother. The retired manager for the Ridpath Hotel and the Spokane Club, he had friends in town who were Japanese, but was uncomfortable bringing up a flag with a likely bullet hole and blood stain.

He was curious about the writing. Even though his sons knew what it was, he could envision a time after he died, when someone in the family would come across it and not know or care about it.

One day, he was working out at a downtown health club when he bumped into Mark Landa, a friend who is the director of academic programs at Mukogawa Fort Wright Institute. He mentioned the flag to Landa, who suggested Costa ask the school’s Japanese Cultural Center for help.

The center regularly translates letters from Japanese into English, or vice versa, and answers questions about other Japanese items. Costa brought the flag, folded in an envelope, to the fitness center a few days later.

“I thought it would only go as far as (the center),” Costa said. Maybe Mukogawa could display it there, which would help preserve it.

The center’s director, Fumihiko Mori, knew as soon as he saw the Nisshoki that it had been given to a soldier going off to war. He’d seen pictures of such heirlooms before, but this was the first he’d seen in person. What was interesting about this flag was the clarity of the writing. The name of the soldier, as well as the names of the friends and co-workers, were readable; so was the name of the factory, Niigata Steel Works. It was clear who the soldier was, and where he was from; but Kodama is a common name in Japan.

Mori thought it would be a good educational project for some Mukogawa students to translate the older form of script, or kanji, as well as practice their English by interviewing Costa and learn some history. He posted a note on a bulletin board asking for volunteers, and five students signed up.

They did four extensive interviews with Mori’s help in translating, looked at all of Jerry Costa’s war memorabilia and eventually went with Duane to his brother’s old home.

“They were kind of shocked. They know almost nothing about the war,” Mori said, adding that’s typical for Japanese of their generation.

Mori had an idea, but he didn’t know what Costa would think. The names on the flag were so clear that it would be possible to take the flag back to Japan at the end of term and try to find someone in Niigata who had signed it and knew Heitaro Kodama.

He doubted there would be any of Kodama’s descendants still alive, but maybe a niece, nephew or second cousin. Or maybe the child or grandchild of another factory worker.

Costa happily agreed.

Shock with the morning news

Toshiaki Kodama picked up his local morning paper on Dec. 28 and had a shock.

There in the Niigata Nippo was a story about some students at Mukogawa University, 250 miles away in Nishinomiya, who had come back from the United States with a flag that had his father’s name on it. At a press conference two days before, they had shown the flag and the name, and asked for help finding anyone who knew about him.

“I was stunned,” the retired publishing company worker, now a grandfather, said. He called the offices of the Niigata Nippo and Mukogawa.

Katsue Kodama was surprised to learn that something so intimate from her late husband – something that wrapped around his body – still existed. It seemed impossible after so many years, she said.

Mori’s colleague at the home school, Toru Fukuda, had cleverly scheduled the press conference for a slow news period between Christmas the year’s end. The original story about the flag had appeared in many of Japan’s major papers, and on the evening news on NHK, the country’s major television network. Word that the family of the flag had been found was also big news.

Interest in the story may have been helped by the fact that Clint Eastwood had been in Tokyo earlier in December for the premier of his latest movies about the war in the South Pacific, “Flags of Our Fathers” and “Letters from Iwo Jima”. The latter has become very popular in Japan, Mori said.

The university offered to have the students and some of their advisers bring the flag to Niigata after they returned from winter break in January.

The Kodamas waited anxiously for Jan. 18, the day of the appointment. The five students and two advisers arrived with the flag rolled in a tube with a soft cloth. Crews from five television stations and some newspaper reporters arrived with them.

The students unrolled the cloth to reveal the flag and Heitaro Kodama’s name.

“I was speechless,” Toshiaki Kodama later told The Spokesman-Review. “My mother and I were all in tears, they never stopped.

“It felt like we finally got to see him, and the two of us just cried.”

They thanked the students, and wrote a letter of their deep gratitude to Costa for the students to translate into English and send to him through the school.

The flag is tattered and frayed at the edges, and dirty. But it carries the name of two of Heitaro’s brothers and some recognizable names from his co-workers. The Kodamas plan to iron out the wrinkles and put it in a frame.

But for now, the flag that spent years folded in an old scrapbook rests rolled up in its protected tube. It is stored with great care in front of the butsudan.

“We put it there, put our hands together in prayer. We told him ‘Welcome home, father,’ ” Toshiaki Kodama said.

That’s more than Duane Costa ever expected, but it’s what he thinks his brother Jerry would want.

“That’s where it belongs,” Costa said. “I’m sure, if it’s possible, (Jerry) is looking down on us and being very grateful for what we’re doing.”