Rethinking celibacy

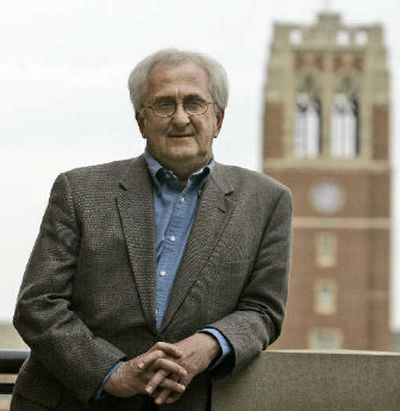

The former seminary president who sparked a national debate on the impact of gays entering the Roman Catholic priesthood is tackling another sensitive issue – adding his voice to those advocating an end to mandatory celibacy.

“Celibacy used to go with priesthood as fish went with Fridays,” says the Rev. Donald Cozzens.

However, he adds, “Over the past 40 to 50 years, I would argue that more and more Catholics are questioning the need to link celibacy with priesthood.”

In “Freeing Celibacy” (Liturgical Press, 128 pages, $15.95), Cozzens suggests there may be a way through the problem by allowing celibacy as an option but dropping it as a requirement.

Although he is taking on an institution that measures change over centuries, Cozzens – a celibate priest himself – thinks the time is right for a rethinking of celibacy.

He points to the brief stir that Brazilian Cardinal Claudio Hummes created last year by saying the Vatican should reconsider its ban on allowing priests to marry, along with the crusade to change the policy by excommunicated – and married – former Archbishop Emmanuel Milingo of Zambia.

“There are a number of factors that are coming together that really beg for this question to be discussed or urge us to review mandatory celibacy,” says Cozzens, who teaches religious studies at John Carroll University, a Jesuit school in the Cleveland suburb of University Heights, Ohio.

There were about 42,000 active priests nationwide in 2005, a 29 percent decline from 1965, according to Georgetown University’s Center for Applied Research in the Apostolate.

About 3,200 parishes were without a resident priest in 2005, compared with 549 in 1965.

“Many, if not most, of the inactive priests would be serving in our parishes if it were not for the law of celibacy,” Cozzens writes.

The church discounts celibacy’s responsibility for the shortage, saying the increasingly materialistic culture plays a far bigger role.

Pope John Paul II was adamant that the church would not change its celibacy requirement. As recently as November, a Vatican summit led by Pope Benedict XVI reaffirmed mandatory celibacy for priests as a non-negotiable job requirement for showing devotion to God and to the people they serve.

Cozzens has been down this road before, having written four other books on issues and problems of the priesthood.

In his 2000 book, “The Changing Face of the Priesthood,” later translated into six languages, he used interviews and studies to contend that the Roman Catholic Church had a disproportionately high percentage of gay priests – nearly half of all seminarians and priests.

His previous writings made a valuable contribution to the debate over homosexuality by raising the issue at a time when many priests and bishops were pretending it didn’t exist, says the Rev. Richard John Neuhaus, editor of the conservative journal First Things.

“It was that climate of, ‘Let’s pretend that we don’t know about it’ that Cozzens blew the whistle on in a constructive way,” Neuhaus says.

Cozzens distinguishes between what he calls the charism, or gift, of celibacy – which he says is an approach freely chosen by only a few priests and nuns – and celibacy as a requirement.

“I am trying to say to the church, the charism of celibacy needs to be celebrated, the obligation of celibacy needs to be reviewed,” he says.

Celibacy as a universal requirement took hold in the 12th century, but priests and bishops were able to marry during the previous millennium.

The Vatican requires celibacy of priests ordained under the Latin rite, although married men can become priests in the Eastern Catholic rites, such as the Byzantine rite of the Catholic Church. The Vatican has accepted some married Anglican priests who came over to the Catholic fold.

The church also has about 30,000 deacons worldwide, including about 15,000 in the United States. Deacons, who can marry, can perform many duties in the church, including baptisms and marrying people, but cannot serve Holy Communion.

Anyone studying to be a priest is aware of the celibacy requirement and should not be surprised by its imposition, says the Rev. Mike Woost, a theology professor at St. Mary Seminary in Wickliffe, Ohio.

Celibacy “is the way we embrace our love of God and our love of God’s people,” Woost says. “This is the way we try to image to the rest of the world the importance of God’s reign in our lives and the life of the world.”

But some studies seem to support Cozzens’ stand.

A 2002 Catholic University of America study found that 56 percent of priests said celibacy should be optional.

A.W. Richard Sipe, a former Benedictine monk who studies and writes about celibacy, estimates that half of Catholic clergy are sexually active at any given time. Church leaders have questioned that finding.

Cozzens, 67, a priest for 41 years, says he has been faithful to the celibacy vow.

“Celibacy has worked in my life and that is due to the grace of God,” he says.

A moment later, however, paraphrasing poet T.S. Eliot, he confesses: “At times I feel it’s cost not less than everything.”