Silent, but lovely

Around 1913, a group of prominent Spokane “society girls” met almost daily at the Davenport Hotel for tea. They called themselves the Little Women.

Then disaster struck sisters Signe and Lillian Auen, two of the Little Women. Their father failed in business, forcing them to venture out into the world and fend for themselves.

And boy, did they ever fend.

Signe Auen became Seena Owen, a major silent movie star who appeared in 67 movies, including D.W. Griffith’s “Intolerance.” She even played a minor role in one of Hollywood’s early scandals: She was one of the celebrities present on William Randolph Hearst’s yacht when director Thomas Ince died under mysterious circumstances.

Lillian became screenwriter Lillie Hayward, writer or co-writer of 77 movies, including “My Friend Flicka” and Disney’s “The Shaggy Dog.”

Most of what we know about their early lives comes from one 1926 interview in the Spokane Daily Chronicle.

“It almost broke my heart to leave Spokane,” said Signe, by then known as Seena. “I was born in Spokane – it was home to me and always will be. And I loved the girls – it wasn’t easy to give up all my friends. I had been so spoiled, too – I was not prepared to earn a living and did not know which way to turn.”

It was a plot right out of the two-reel silent movie melodramas of the era: Rich girl humbled by ruin.

Lillian was born around 1891 (give or take a year) in St. Paul, Minn.; Signe was born in Spokane on Nov. 14, 1894. They grew up in an affluent Spokane family that owned the downtown Columbia Pharmacy and an associated medical supply company.

Signe, according to a 1924 bio in Photoplay magazine, attended school at Brunot Hall in Spokane (a fashionable Episcopalian school for girls) and spent her afternoons having tea at the Davenport. Some accounts say she spent some time abroad in Copenhagen. After graduation, she moved in with her older sister at 905 S. Monroe.

Then, the entire Auen family disappears from the 1915 Spokane City Directory (compiled in 1914). Signe, for one, headed to California. She was only 19 or 20.

“I had taken elocution lessons from Pauline Dunstan Belden and somehow she had put the stage ‘bug’ into my head,” Seena told the Chronicle. “Being an actress appealed to me more than being a stenographer or a nurse – so I decided to come to California to try my luck. At first I played a few little parts on the stage in San Francisco. I earned $5 a week doing a maid part.”

Yet in the exploding field of motion pictures, stage experience wasn’t necessary – or even desirable – for a film actress.

So Signe ventured down to Hollywood and waited in line day after day trying to land a movie part. One day she was walking down the street when she spotted a familiar face, actor-director Marshall (Mickey) Neilan, a Hollywood “boy wonder” still in his 20s. He would later become one of early cinema’s most influential directors.

“I had known him in Spokane when he was with the Peytons (a family prominent in Spokane business),” Seena told the Chronicle. “He was lovely to me and took me out to his studio, where he gave me a job at $15 a week. After that, I began to get some better roles – but it was long, bitter struggle to stardom.”

Not that bitter. Not that long.

A rising star

Producers soon discovered that the camera loved Signe. The All Movie Guide says that she was “praised by virtually every cameraman of the silent era as being one of the greatest natural beauties, impossible to photograph badly.”

Through 1914 and 1915 she began to win increasingly larger roles, culminating in 1915’s “The Lamb” in which she starred opposite one of the world’s biggest stars, Douglas Fairbanks.

The co-screenwriter of “The Lamb” was D.W. Griffith, who was making movie history that same year with “The Birth of a Nation.” According to Hollywood legend, Griffith was at first unimpressed with what he called Signe’s “cool composure,” and told her she was too unemotional to be an actress.

She answered, “Then I’m an actress because I’m trembling inside.” Griffith immediately hired her for his company.

That story may have been embellished by publicists, but Signe soon became one of Griffith’s top actresses. Some sources claim it was Griffith who urged her to change her name to Seena Owen, a more-or-less phonetic version of Signe Auen.

This happened at just about the time that the term “movie star” was gaining currency. Previously, actors and actresses were anonymous, known strictly by nicknames such as “The Biograph (Studio) Girl” or “The Little Girl With the Golden Curls,” who the public later learned was named Mary Pickford.

“The Lamb” was the first movie in which Signe was credited as Seena Owen. It was also one of the first that made the folks back home take notice.

On June 4, 1916, The Spokesman-Review wrote, “Probably the most notable Spokane contribution to the films is Seena Owen, formerly Signe Auen, now among the regular leading women of the Fine Arts Studio.”

The story went on to say that Miss Owen’s biggest part was yet to come, “her characterization of Babylonia in the new Griffith masterpiece, ‘The Mother Law.’ “

The movie was actually called, “The Mother and the Law,” but it was soon destined to go down in history under a new name, “Intolerance: Love’s Struggles Through the Ages.”

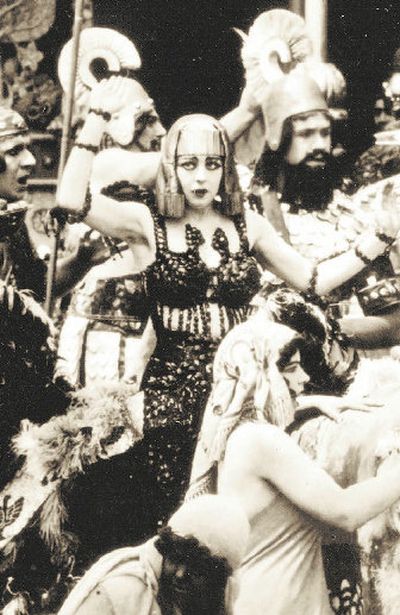

This was D.W. Griffith’s vast, ambitious – and financially ruinous – “film fugue” about the price of intolerance from the age of Babylon to the present day. Owen had a plum role as the sexy and elaborately head-dressed Attarea, the Prince’s Beloved (sometimes called the Princess Beloved).

The movie was a bomb – audiences just didn’t understand it – but it is now considered one of the most influential and important movies of all time. The monumental Babylonian set was also where Seena met George Walsh, an actor and the brother of director Raoul Walsh, whom she married in 1916. “Intolerance” also represented the artistic peak of Seena Owen’s career, even though she was only 22 at the time.

She went on to make dozens of other movies opposite legends such as William S. Hart and Lon Chaney, but most were unmemorable melodramas such as “A Woman’s Awakening,” “The Cheater Reformed” and “A Fugitive from Matrimony.”

Still a Spokane girl

Owen was still, unquestionably, a star when the Spokane Chronicle sent a reporter to a Hollywood film set to interview her in 1926. Reporter Irene Burns wrote that the actress was “prettier than ever – she has lovely blond hair and immense brown eyes.”

“Fame has not changed this well-known star in the least,” wrote Burns. “Everyone in the studio loves Seena, from the property man to the director.”

Burns also mentioned that Seena was now divorced from George Walsh and had an “adorable little girl 9 years of age.” Yet Burns failed to mention that the divorce was acrimonious and sensational. The Los Angeles Times ran a series of stories in 1922 detailing all of the tawdry charges, including Seena’s account of the day, at New York’s Plaza Hotel, in which she found a love letter to Walsh from another actress. Walsh grabbed for the letter and a “tussle” ensued, but Seena locked herself and the letter in the bathroom. According to one much later account, Walsh claimed that Seena tried to kill him.

Burns also discreetly failed to mention Seena’s small role in the 1924 William Randolph Hearst yacht scandal. Ince, a pioneer filmmaker, became mysteriously stricken during the yacht party, was removed from the yacht under hush-hush circumstances, and died shortly afterward. Whispers persisted for decades that Hearst had shot Ince for flirting with Hearst’s mistress, Marion Davies. Another version of the rumor had Hearst aiming at Charlie Chaplin, who was flirting with Davies, and shooting Ince instead.

Seena was one of about 13 movie people on board the yacht; she was never implicated in any wrongdoing. In fact, nobody was ever officially implicated in any wrongdoing – Ince probably died of a heart attack – but rumors persist to this day. The 2001 Peter Bogdanovich movie “The Cat’s Meow” was based on these rumors.

Seena was at pains to demonstrate in the Chronicle interview that she was just a simple Spokane girl at heart.

“I miss Spokane – especially the girls,” Seena was quoted as saying. “They are the keenest girls I’ve ever met. I think they dress better than girls in any other city, too. I expect to go to Alaska soon to begin work on my next picture, ‘Flame of the Yukon.’ When I do mother and I are going to stop in Spokane for a visit. We’re both dying to go back.”

The end of an era

Seena had no way of knowing that the entire film industry – and her own career – would change course dramatically the next year. “The Jazz Singer,” the first true talking picture, arrived in 1927 and suddenly the silent movies were dead. Seena was one of the casualties.

By one account, the talkies exposed her “flat and listless” voice – despite all of those Spokane elocution lessons. It is equally possible that she was simply nearing a dangerous age for an actress at the time, her mid-30s.

She continued to land a few movie roles, including one 1929 plum, Erich Von Stroheim’s “Queen Kelly.” She plays the insane Queen Regina, who goes berserk and whips Gloria Swanson through the halls of her castle. Excerpts from that scene were included in Swanson’s 1950 classic, “Sunset Boulevard.”

But after making “Officer Thirteen” in 1932, her movie career ended. Her movie career as an actress, that is.

Seena went on to a new career as writer or co-writer of eight movies. In that, she was following in the footsteps of her older sister, Lillian, by then known as Lillie Hayward.

“The Film Encyclopedia,” by Ephraim Katz, says that Lillie was a former musician who became a script editor in 1919 and went on to work for numerous studios as an editor, original story writer and screenwriter all the way up to the 1960s. The encyclopedia and other references do not make the connection with Seena Owen. The only reason we know that Lillie Hayward is the former Lillian Owen is because of a few lines in that 1926 Chronicle interview with Seena.

“Lillian Hayward is one of the foremost scenario writers of the silver sheet,” said the story.

The two sisters even collaborated on one movie, the 1941 Dorothy Lamour sarong epic, “Aloma of the South Seas,” in which Seena is credited with the story and both are co-credited for the screenplay.

Seena’s writing highlights were 1937’s “Rumba,” a Carole Lombard-George Raft vehicle and “The Great Man’s Lady,” a 1942 Barbara Stanwyck-Joel McCrea drama. Seena’s last writing credit came in 1947.

Lillie’s list of movies is much longer, encompassing B-movies such as “Night Club Scandal” and “Expensive Husbands” in the 1930s; animal-oriented family movies like “My Friend Flicka,” “Banjo,” “Smoky” and “Black Beauty” in the 1940s; and Disney movie and TV productions such as “The Shaggy Dog,” “Toby Tyler” and the “Mickey Mouse Club,” in the 1950s and 1960s.

Lillie delivered her last script in 1962. But even in 2006, if you looked closely at the credits for the Tim Allen remake of “The Shaggy Dog,” you would have seen Lillie Hayward credited for the original screenplay.

Seena Owen died in Hollywood on Aug. 15, 1966. Lillie Hayward followed on June 29, 1977, also in Hollywood.

Their deaths passed without mention in the Spokane newspapers. After that 1926 interview, it seems that Spokane had forgotten about the Auen sisters.

Yet the fact remains: They were two of the keenest girls ever to come out of Spokane.