Freeway at 50

Interstate 90 is our road most traveled, but 50 years ago it was hardly even imagined, at least in the form we know. And it took almost four decades for it to be completely realized in Eastern Washington and North Idaho.

Now I-90 serves as the region’s economic and social artery, reliably connecting the Inland Northwest to the nation, providing faster local transportation and transforming the community from a regional hub to a part of the global market.

This year both the national interstate system and I-90 celebrate their 50th anniversaries.

A new kind of highway

High ceremony accompanied the Nov. 16, 1956, grand opening of the first five miles of what was then called the Spokane Valley Freeway.

Miss Spokane and Miss Spokane Valley cut the red ribbon opening the freeway from Custer Road, near what now is known as the Havana Street exit, to Pines Road in the Valley.

At the time, Spokane County Sheriff Roy Bettach worried about children playing near the freeway, and urged that its entire length be fenced. Children were riding bikes and wagons down the steep slopes near Pines Road, and running right across the freeway lanes, oblivious to the high-speed traffic.

Two sections opened in the Spokane Valley before the first segment opened in the city of Spokane in 1958.

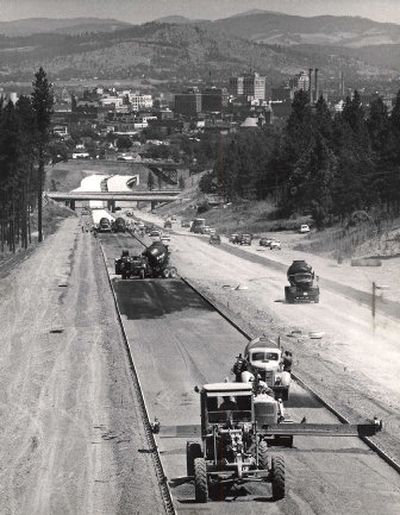

Howard “Red” Rebe began working for the Washington State Department of Transportation in the early 1960s building the freeway, which was originally two lanes in each direction.

“We knew it was big. We didn’t know how big,” Rebe said of I-90’s importance.

Spokane Valley City Councilman Gary Schimmels poured concrete for the portion from the Sunset Hill to Four Lakes.

“We had kind of a revolutionary crane. It ran on railroad tracks on the north side of the freeway,” said Schimmels. The crane allowed crews to pour 90 percent of the concrete from that side.

But at the time Schimmels said he didn’t think he was building history. “I had a good job,” making $7 or $8 an hour.

Coeur d’Alene saw its first section of freeway open in 1960 between Northwest Boulevard and Sherman Avenue. Called the Coeur d’Alene belt route at the time, it wrapped around the edge of town, said Larry Wolf, a retired Idaho Transportation Department assistant district engineer, who worked on freeway projects for 30 years.

“At that time it was way out of town, way north of town,” Wolf said.

Today that “belt” route cinches Coeur d’Alene around the midsection.

From there Idaho extended the freeway west toward Post Falls and the state line.

James McGoldrick, once the director of the Spokane Area Good Roads Association, was a huge proponent of the freeway.

The first time he drove the freeway in Spokane, “God, it was a fantastic thing. It was a momentous occasion,” McGoldrick said.

“The community grew up because of the I-90 freeway,” he added. “It was the major thing that happened for Spokane. … It connected it to the whole rest of the country.”

National push

Freeways were being built all over the country in the 1950s.

Washington State Transportation Commission member Dale Stedman said he first saw a freeway on a trip to Los Angeles. The elevated on-ramps and exits were impressive, said Stedman.

“Look at this. It’s like Buck Rogers,” he thought at the time.

An employee at the Inland Automobile Association when the Spokane Valley Freeway was being built, Stedman recalls the push for a nationwide interstate system as an exciting experience.

During the Eisenhower presidency, the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956 officially created the interstate system by establishing a program to fund building it.

Contrary to popular belief, its primary purpose wasn’t for defense, although the interstate system’s military value was immediately recognized. The main reason the system was created was to support civilian needs such as improving safety and congestion.

Today there are 46,876 miles of interstate. That’s above the current cap of 42,795 miles, meaning miles built above the cap aren’t eligible for federal interstate funds.

I-90 is now the longest freeway in that system, running 3,020 miles from Seattle to Boston.

Contested path

I-90’s route through Spokane was hotly contested. Had some people gotten their way, I-90 might have been built along downtown Spokane’s Riverside Avenue and Main Street, taking out the Spokane Club, narrowly missing Our Lady of Lourdes Cathedral, and demolishing what was then Spokane City Hall.

Others called for a tunnel under the South Hill.

But while the present route was deemed the most affordable and practical, it had its own problems.

The project stalled for years when Deaconess Hospital sued in 1963 to stop the downtown freeway viaduct from being built nearby.

Hospital administrators feared the noise from passing traffic would prevent patients from properly healing.

They were successful at first, winning their case against the project. But the Washington Supreme Court ultimately overturned that decision in 1965, allowing the freeway viaduct to be built downtown.

In the meantime, the completed Latah Bridge sat empty.

“I remember as a teenager skateboarding down the Sunset Hill before it was open,” said Spokane Association of Realtors Executive Director Rob Higgins, a former City Council president.

Higgins and his friends would sneak a car onto the deserted freeway at night and then skateboard by the glow of the headlights. “It’s amazing we got a car on there,” he said.

The freeway forced many in its path to relocate their homes and businesses, especially in Spokane’s East Central Neighborhood.

Hundreds lost their homes, and the freeway claimed many other buildings, including the First Church of Christ Scientist, Alcott Elementary and even the Inland Automobile Association’s new headquarters.

Liberty Park, once one of the gems in the Spokane park system, was reduced in size by half.

Safety

Increasing driver safety was one of the selling points for the freeway.

Limiting access eliminated crashes resulting from people pulling out of driveways into high-speed traffic.

And Spokane touted the safety of its new freeway with the “Deathless Freeway” charity contest. A variety of groups and businesses participated. If no one died on the freeway on that group’s day, it donated $12 to the charity of its choice. A running tally was published each day in the Spokane Chronicle.

The contest raised more than $4,000.

It wasn’t until more than a year after the first section opened that someone was killed – Dennis Earl Perkins, of Omak, who got out of a car and was hit running across the westbound lanes near Flora Road.

The tragedy was marked by a citizen’s poem printed in the Spokane Chronicle, which said in part:

Then all at once the lighting struck

Four million cars had gone their way

No riders lost, yet Death stepped in,

The Freeway lost a life one day

Over the years innovation improved safety on the freeway, said Rebe.

Jersey barriers work better than old guardrails at stopping traffic. Lighting has improved. Interchanges feature gentler curves and longer merge lengths.

And I-90 in Spokane was one of the first places where magnesium chloride was used to clear snow and ice rather than salt. It was tested here in the early 1980s, said Rebe.

Crashes, mishaps, blunders

The interstate may be more reliable than a two-lane highway, but building and driving on I-90 hasn’t always gone smoothly.

Two men were thrown from the falsework supporting the Latah Bridge west of Spokane in 1962. One died.

Also that year, freeway blasting was blamed for drying up Garden Springs homeowners’ wells.

In 1990, 100 30-foot Austrian pines planted as part of Lady Bird Johnson’s highway beautification program were mistakenly cut down by WSDOT contractors in front of Spalding Auto Parts.

The contractor believed they were within 17 feet of the highway, inside the prescribed safety zone.

If anyone had bothered to measure, they would have discovered the trees were 37 feet away.

And there have been some spectacular crashes.

On an icy day in January 1968, a 50-car pile-up brought interstate traffic to a standstill in Spokane. No one died in that crash.

A tractor-trailer carrying 44,000 pounds of margarine rolled on its side in 1979, dumping its load of tubs all over I-90 in east Spokane. No slipping and sliding accidents, but the artery was clogged for hours.

One of the scariest I-90 incidents happened on Christmas Eve 1991, when a freight train derailed over the freeway’s Latah Creek bridge, dumping cars and debris onto the roadway. A Greyhound bus narrowly escaped the falling train.

Now what?

The last local portion of I-90 was completed in 1992, when it was moved off the lakeshore east of Coeur d’Alene and onto the Centennial Memorial Bridge.

That bridge was built using a unique method, Wolf said. Rather than bringing in precast pieces, all the concrete was poured on site.

“Without Interstate 90 you can only imagine the antiquated roads you’d be traveling on,” Wolf said.

Idaho was also home to another I-90 last – its last stoplight. That light was dismantled in Wallace in 1991 when the viaduct bypassing the small mountain town was completed.

Town officials held a funeral for the light.

“Like the whippet and the buttonhook, the iceman and the lamp lighter, the livery stable and the company store, cruel progress has eliminated the need for the services of our old friend,” remarked Wallace City Councilman Mike Alldredge at the time.

The ceremony took on a celebratory nature, but within days Wallace businesses began to feel the drain of dollars as traffic bypassed the town.

Spending on I-90 itself has slowed in this area, even as increased traffic is testing both its capacity and durability.

In 1960, the Washington State Department of Transportation counted 19,800 vehicles per day between the Havana and Sprague interchanges. Last year that number hit 105,000.

In Idaho, average daily freeway traffic counts in Post Falls have grown from 28,475 in 1990 to 48,877 last year.

Washington completed a project last year to widen I-90 from Argonne to Sullivan, but neither state has money allocated at this time to build additional lanes in this area.

So the interstate that 50 years ago drove the Inland Northwest firmly into the auto age, now struggles to keep up with growth in the 21st century.