In this case, a picture’s worth 12.8 billion years

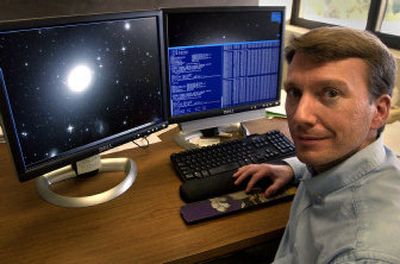

PULLMAN – The tiny, pixilated red smudges on John Blakeslee’s computer screen may not look like much.

But they’re the clearest pictures yet of the early universe, almost 13 billion years ago. The smudges are some of the oldest galaxies scientists have ever spotted, which are alight with the first stars in the universe.

“What we think we’re seeing is this epoch where the universe first started,” said Blakeslee, an assistant professor of physics and astronomy at Washington State University. “These are the faintest objects that have ever been detected.”

Blakeslee and colleagues at other universities have analyzed hundreds of such smudges as they study the deepest photographs of space, which include the Hubble Ultra-Deep Field, taken in 2004. The scientists found roughly 500 galaxies in their analysis of an area of the sky just a fraction of the size of the moon, as seen from Earth.

The galaxy census helps researchers count how many galaxies were being formed about a billion years after the Big Bang. It also may help answer how the universe went from a mostly cold, dark state to erupting with energy and matter.

The galaxy survey is significant, considering that a decade ago scientists hadn’t viewed any images of galaxies dating back to the first billion years of the universe.

The Hubble images are like a look back in time – the light from stars and galaxies has traveled many light years to reach Earth, and the farther away the objects are, the further back in time the light originated.

So when Blakeslee and his colleagues examine the tiny red smudges, they’re looking at a moment in time that’s 12.8 billion years old.

“As you go further back, the galaxies don’t look so nice and regular,” he said.

This new image of the early universe helps support one view of the way things began, after the universe cooled down after the Big Bang. It was unclear whether star formation or something else – such as matter falling into black holes and emitting jets of energy – was the main factor in the reheating of the universe.

The work of Blakeslee and his colleagues shows that star formation could have been the force behind the reheating.

“Seeing all of these starburst galaxies provides evidence that there were enough galaxies 1 billion years after the Big Bang to finish reheating the universe,” said team member Garth Illingworth, of the University of California, Santa Cruz. “It highlights a period of fundamental change in the universe, and we are seeing the galaxy population that brought about that change.”

Blakeslee worked primarily on software that could help analyze the images, pixel by pixel. Reading starlight is an incredibly complex process, which includes calculating the “red-shift” to determine how far away objects are.

That’s the shift toward the red end of the visible spectrum in light that travels through the universe, and it’s caused by the expansion of the universe – the farther light is shifted toward the red end of the spectrum, the farther away it is.

The Hubble project, launched in 1990 and updated several times, has been the deepest telescopic work in history, most recently with the Advanced Camera for Surveys, or ACS, which Blakeslee and many other scientists helped develop. The next step in deep-space imaging could be the James Webb Space Telescope, which aims to unfold a giant mirror in space to gather even deeper views.

In the meantime, attempts to view even earlier or fainter galaxies from the early universe will be difficult, because that light can only be captured by infrared cameras, which are less advanced, he said. “It’s just many, many, many times harder,” Blakeslee said.