Texas Camel Corps

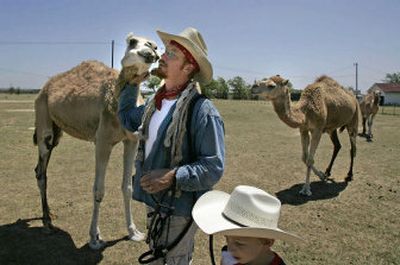

VALLEY MILLS, Texas – In the rolling, wide open country of Bosque County, where one Central Texas ranch resembles another, the directions Doug Baum gives to his place are distinctive: on the corner, white house, red roof, camels in the yard.

Sure enough, hundreds of miles from the nearest desert, a half-dozen camels are munching on leaves in the nearly 100-degree heat.

The animals comprise the Texas Camel Corps, Baum’s tribute to an almost forgotten chapter of the state’s history and an opportunity for the adventurous to get a taste of the Bedouin life – Texas style.

The animals also have been known to halt the sparse traffic along this rural road.

“I’ll get a group of guys on motorcycles driving by,” says Baum, 38. “They’ll rubberneck and pull in. I don’t mind. I’ll share them.”

For some eight years now, Baum and his camels have led folks on treks replicating a mid-1800s federal government experiment to introduce the animals to Texas. The trips include a journey into what then was the unexplored rugged but spectacular Big Bend area that ultimately became a national park along the Texas-Mexico border.

Not coincidentally, the Big Bend is among the areas where Baum takes people on overnight trips, along with Monahans Sandhills State Park in West Texas. Unlike the rocky desert and mountains of the Big Bend, the Monahans trek features Sahara-like sand dunes up to 70 feet high.

“It looks like what you think a desert should look like,” he says.

And bowing to the reality of high fuel prices, he now welcomes visitors who prefer to travel closer to home to his place outside Valley Mills, about 30 miles northwest of Waco.

Baum became interested in camels, oddly enough, while working as a drummer in a country music band.

He grew up in Colorado City, about 100 miles southeast of Lubbock, and went to Nashville, Tenn., after earning a degree in music. He toured with the band fronting Trace Adkins and opened for Brooks & Dunn, but there wasn’t a whole lot to do in Nashville during the day, Baum says.

So he volunteered to do chores at the zoo, a job he also did while in school in Waco.

“I fell in love with the camels,” he says.

Baum decided to make it a career after getting married and starting a family. He says it didn’t feel right for him to be boot-scooting on the road while the brood was back at home.

“When I discovered the whole Texas history angle, there was my validation for having camels in Texas,” he says. “I came up with the camel trek idea.

“I’ve always been interested in culture and history, and it seemed a camel trek was the perfect combination with education.”

Camels first were brought to Texas in 1856 at the urging of Jefferson Davis, the future Confederate president who was the U.S. secretary of war at the time.

Davis, a veteran of the Mexican-American war, was familiar with the desert Southwest, and the animals were assigned to Army troops and based near present-day Kerrville, northwest of San Antonio. During the Civil War, some camels were captured by Confederate forces. After the war, the animals, never a favorite of the troops, were sold off.

Baum started his camel career 1993, bringing two camels from the Nashville zoo back to Texas and featuring them at school and museum presentations and living history programs.

“I saw the reaction and started building on it from there,” he says. “I knew the ultimate goal was education in camels in some form other than a sideshow. There’s great money in kiddie rides. I’ve done them, but it’s not my focus.”

By 1999, he was leading treks from his home. Some who’ve been on a trek says it was a unique experience.

“I have a lot of outdoor interests, and camel trekking fits in nicely with that,” says John Horne, a Houston-based land surveyor who went to the Big Bend with Baum last fall.

“My aim was to gain as much working knowledge of camels as possible on that trip, as well as break through the ‘dude’ stage of my camel education.”

Horne, 50, uses words like “fantastic” and “incredible scenery” to describe the trip, which Baum designs as not merely a tourist camel ride. For example, the camels for the most part carry gear, food and, importantly, water.

People walk.

“It’s hard, hard going,” Baum says. “I think it’s fun, but I try to make sure people know it’s going to be rough. … You wouldn’t want to do it with kids, especially in the summer. It’s work. I don’t try to make it hard on folks, but it is what it is.”

It also provides steady work for the father of three, except during the summer. Then it’s just too hot to wander the desert, even with animals bred over thousands of years to tolerate heat. One particularly busy time is the Christmas season, when camels are in great demand for Nativity programs.

Baum quickly exhausted the readily available camel expertise in Texas, but he found a Bedouin family in Egypt willing to teach him the subtleties of camel handling.

“What I know is this much,” he says, holding his thumb and index finger slightly apart. “A Bedouin family could fill a tanker. I’m still learning every day.”

He does have enough expertise to frequently shoot down the myth that camels store water in their humps. The hump – one on an Arabian camel, the most common species, and two on Bactrian camels – actually is made up of body fat.

He’s also come to appreciate the personalities of his animals, which range from a 450-pound, 1-year-old newcomer yet to be named to a 2,000-plus-pound, two-hump camel named Gobi.

“The camel is highly, highly sensitive and easily insulted. You more suggest to a camel than demand,” says Baum, who got several of his camels from a herd in Arizona, where he works with Vision Quest, a placement agency for at-risk youth.

Baum says camels don’t scare easily, theorizing it’s because they have no predators in the desert and don’t have a “fright response.”

He thinks they never really caught on here because of the stigma of being associated with rebel leader Davis after the Civil War and because of the dominant horse culture of the American West. But he does think they’re smarter than horses, and other than working cattle, they can pretty much do anything a horse can.

“I understand they’re a curiosity and an oddity to our countrymen,” he says. “But I’m finally getting to the point where I can look and not see them as strange.”