Forgotten fullbacks

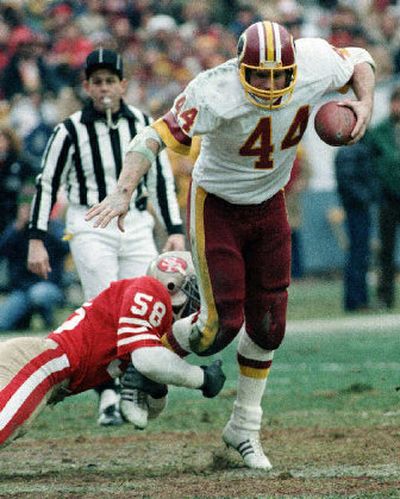

John Riggins was the type of player kids loved emulating.

He was a bruising runner with a mean streak and big shoulder pads who plowed through defenders and dragged them along for the ride – all the way to the Hall of Fame.

But that was back in a long-lost era when fullbacks were ball-carrying bulls and integral parts of team’s game plans. Today, being a fullback just doesn’t have that attractiveness.

“A fullback now is kind of a tight end and a lineman,” said Riggins, who played for the New York Jets and Washington from 1971-85. “They’ve got to be able to pass block and drive block – it’s almost like a pulling guard. That really is as good as it gets for a fullback in contemporary NFL football, with the exceptional draw play, of course.”

Kids don’t want to be fullbacks anymore. It’s not a glamorous position, and at least two teams – Dallas and Indianapolis – don’t carry any true fullbacks on their active rosters.

“It’s really hard to find guys that still want to do it, go in there and pound and hit people in the mouth,” Minnesota’s Tony Richardson said. “We’re kind of the last of a dying breed.”

Some of the game’s greatest runners were primarily fullbacks: Riggins, Jim Brown, Franco Harris, Ernie Nevers, Bronko Nagurski, Marion Motley and Larry Csonka – all Hall of Famers. They carried the ball, caught it and blew open holes for running backs.

Fullbacks are mainly blockers now who catch occasional passes and rarely carry the ball. Last weekend, 20 of 32 teams started with a fullback lined up in the backfield. Of those, 14 were actual fullbacks. Five others were tight ends, and one, Dallas’ Oliver Hoyte, was a linebacker. And that doesn’t include Seattle fullback Mack Strong, who lined up as a wide receiver to start the Seahawks’ game at San Francisco.

Only three fullbacks – Tampa Bay’s Mike Alstott, Carolina’s Brad Hoover and Oakland’s Zack Crockett – had at least five carries Sunday.

The position has also seen a dropoff in the college ranks, with many schools filling the spot with any big bodies available.

“I think the traditional go-ahead, get-in-the-hole fullback is not here any more,” said Alstott, a six-time Pro Bowler. “You try to disguise things and put fullbacks in the slot, use them as tight ends, and you have to get unique players (to fill those roles).”

The position gradually has evolved – or devolved, depending on who you talk to. The last fullback drafted in the first round was William Floyd in 1994. Only nine have been taken in the second or third rounds since 1997.

“I don’t think that it’ll ever be extinct, but it’s pretty darned close,” said Gil Brandt, a senior analyst for NFL.com, who was Dallas’ vice president of player personnel from 1960-89.

In the last 10 drafts, 14 tight ends have been taken in the first round, and 49 in the second and third rounds. Teams generally see more value in drafting tight ends who can catch, block and line up as fullbacks the way Dallas’ Anthony Fasano and Washington’s Mike Sellers do, to name a couple.

“Everybody wants one-stop shopping,” Brandt said. “That’s what you see teams doing with their offenses. You see these trends and you see them come and go in cycles.”

But this cycle has been in the making for years. Many attribute the change in the role of fullbacks to Washington coach Joe Gibbs, who was the first to consistently spread out the offense and use an H-back in the early 1980s. Riggins went from sharing carries and blocking to running the ball on a regular basis.

“I can say it was the greatest day of my life when he decided he wanted to just use one back, and I happened to be that guy,” said Riggins, the 1983 Super Bowl MVP. “From my take on it, I think the toughest job as far as the purely toughest guys – and I’m not saying I was one of them – is the fullback and middle linebacker, because those guys have to go toe to toe. For my money, that was never a whole lot of fun.”

Alstott’s career has been the opposite of Riggins’. He was primarily a runner earlier in his career, gaining as many as 949 yards in 1999, and is Tampa Bay’s career touchdown leader. The fan favorite has become mostly a blocker since Jon Gruden arrived as coach in 2002, although he still starts and carries in short-yardage and goal-line situations.

“It’s a dirty job,” Alstott said. “You start 5 yards away, and you and the linebacker run at each other and hit like two rams, over and over and over again.”

The teams that still have traditional fullbacks recognize their value.

“They have a fullback they use, maybe not every down, but a guy who can get a first down or run out into the flat and catch a pass, get you a first down, get you some yards – as well as move people when you are running the football and clear the way for the tailback,” Seattle’s Strong said. “You just don’t see as many guys having those abilities.”

San Diego’s Lorenzo Neal is the epitome of the blocking fullback, having paved the way for 1,000-yard rushers – the New York Jets’ Adrian Murrell, Tampa Bay’s Warrick Dunn, Tennessee’s Eddie George, Cincinnati’s Corey Dillon and the Chargers’ LaDainian Tomlinson – in each of the last 10 seasons.

“I think it’s a heartbeat of the team on offense,” Neal said. “It’s a trendsetter. You go ask the Rams, go ask those linebackers. Call up the guys over in Baltimore, ‘Hey, how do you like it when Lorenzo comes in there?’ If the guy comes out there and he’s hitting, boom, they don’t like it. If you can bring that attitude, perfect.”