L.A. orders a farewell to palms

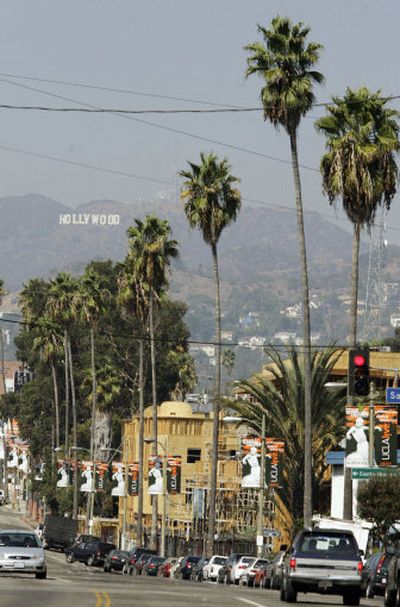

LOS ANGELES – Its streets aren’t paved with gold. For nearly a century, though, Los Angeles’ roadways have been lined by what some say is the next best thing.

But with a City Council vote last week, the reign of the fan palm – that tall, skinny, bush-headed tree that is symbol of L.A.’s balmy, postcard lifestyle – is waning.

Los Angeles leaders have halted the placement of the skinny, frond-topped fan palm on parkways, median strips and other city-owned property where nearly 75,000 of them now grow.

Instead, the city will only plant sycamores, oaks and other leafy native species that will contribute shade, collect rainwater and help release oxygen across the Los Angeles basin.

The fan palm may be an emblematic part of Los Angeles, but its skimpy canopy is cheating city dwellers from the benefit of real trees, City Council members say.

That’s because palms “are technically a type of grass and not trees,” as a unanimously approved council resolution put it.

Councilwoman Janice Hahn’s motion, passed Tuesday, limits future use of palms along city streets unless they are needed to be consistent with existing plantings or are specifically requested by a council office or community group. If new palms are planted, “fan palms should be discouraged” and shorter, more-densely fronded queen and king palms or Canary Island date palms should be used instead.

The vote comes as many fan palms planted by developers in the late 19th and early 20th centuries are beginning to hit the last phase of their lifespan. It also comes as the city is embarking on Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa’s ambitious goal to plant 1 million new trees.

The city’s phaseout is being greeted glumly by those who view the palm as an iconic image that’s right up there with the Hollywood sign, Rodeo Drive and the movie premier searchlight in defining Los Angeles’ sense of place.

“The palm tree is one of the first things that comes to mind when you think of Hollywood, Los Angeles, Beverly Hills,” said Edmond Avakian, manager of Palm Limousines of Van Nuys. “It’s a symbol of glamour and the good life.”

Timothy Phillips, superintendent of the Arboretum of Los Angeles County, agreed. His Arcadia preserve contains fan palms planted as early as the 1860s and ‘70s by legendary developer Lucky Baldwin.

“It’s ridiculous. The palm brings a sense of prosperity. The palm is Hollywood,” Phillips said. “It would be a shame to lose such an icon. Removing the palm from the street tree program is a knee-jerk reaction. They are very suitable for our climate and aesthetically pleasing.”

He also disputed the city’s assertion that the palm is a grass. “That’s biologically impossible,” Phillips said.

But the end of the palm tree era has been slowly creeping up on Los Angeles.

For more than a dozen years the fusarium wilt, a fungus that is endemic to local soil and is lethal to palms, has been systematically killing them, especially the Canary Island date palm. The fungus has often been spread between trees by contaminated chain saws used by tree-trimmers cutting down dead fronds.

Recently, the replacement of infected palms and the planting of new ones has been slowed by the lack of an affordable stock. Landscapers say the cost has been driven up by the purchase of vast stands of palms for use at glitzy new Las Vegas casinos and Phoenix commercial developments.

Surprisingly sturdy because of a heavy, clumped root system, fan palms began popping up in Los Angeles in the 1880s when property owners imported seedlings. Specialized palm nurseries were in operation by 1900 as a palm-planting spree hit the city. Thousands of them were planted in a citywide beautification effort prior to the 1932 Los Angeles Olympic Games.

In the wild, the two most common street palms, the California fan palm and the Mexican fan palm, grow 40 to 60 feet high. They shoot up to the 150-foot range when planted in irrigated areas, however.