The point of many returns

Behold Mount Baldy, looming majestically above Spokane at 5,883 feet. This is the Spokane area’s undisputed high point, catching every eye and every snow cloud.

Those of us beholding it since 1912, however, know it by another name: Mount Spokane.

Before 1912, its official name was actually Mount Carlton (or Carleton), but most of Spokane’s early residents ignored that name and called it Mount Baldy or Old Baldy because it showed clear evidence of male-pattern-baldness.

Around 1900, one Spokane man fell in love with Old Baldy: Francis H. Cook, the publisher of Spokane’s first newspaper, the Spokan Times, and the man behind the development of Manito Park. Cook stared up at that mountain, climbed to the top, and had reveries about its future. He dreamed of the day when it would become a public park, a popular vista point, and an elevated – and elevating – place to renew the spirit in both summer and winter.

So in 1908, he bought about 160 acres at the summit and made plans to build a tramway to the top. When that plan proved too grandiose, he pared it down to a more manageable dream: Building a road to the top.

He built a vacation cabin on the mountain’s shoulders, and he and his son, Silas, then spent seven years between about 1908 and 1915 hacking a road up through the mountain’s ponderosa pines, tamarack and sub-alpine firs. They built a second cabin at about 5,000 feet, where skiers would later schuss.

In 1912, Cook organized a ceremony at the summit to officially change the name from Mount Carlton to Mount Spokane, which Cook believed was the mountain’s original Indian name. Cook operated the rough road as a toll road, charging 50 cents a car. Just before his death in 1920, he pledged his land to the state with the proviso that it be made into a public park. Other public-minded landowners later followed suit.

On July 8, 1927, another line of autos snaked their way to the top for a momentous occasion: the dedication of Mount Spokane as a state park. This was a matter of considerable pride in the Inland Northwest. It was the biggest state park in Washington and the first state park east of the Cascades. Also, the auto road was the highest auto road in the state, surpassing by 300 feet the road to Paradise Lodge on Mount Rainier. Boy Scouts were stationed with water at the hairpin turns to assist motorists with boiled-over radiators.

“In ancient times our fathers set aside certain cities as places of refuge from persecution,” the state land commissioner said in a grand oration. “Today there has arisen a need for refuge from the demands of modern life and business. We are building sanctuary where the avenger called outraged nature may not come.”

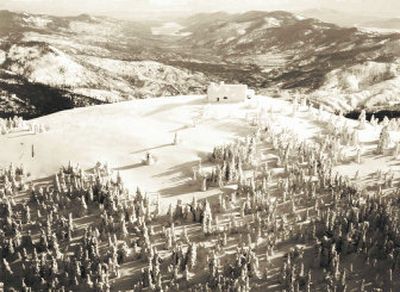

For the first few years, the park’s prime season was summer; its prime appeal was its view. On a clear day, some claimed, a person could see 14 lakes, three states and two sovereign nations. To accommodate sightseers, the rustic stone Vista House was constructed in 1933 – it still presides over the summit.

Then, when the Great Depression hit, the mountain went into service as a work-relief project. A Civilian Conservation Corps camp was built high on the mountain in 1934. Hundreds of workers labored on park roads, cabins, lookouts and other improvements. The camp’s name: Camp Francis H. Cook.

Right around this time, a new fad had arrived from Europe: “the ski craze.” Immediately, eyes turned to Mount Spokane. A Spokane Ski Association was formed in 1930, headed by Cheney Cowles, another important Mount Spokane booster, followed by the Selkirk Ski Club and the Mountaineers. The clubs built their own small lodges, followed by the state park’s public lodge, built by the CCC in 1940.

Those earliest skiers were more like back-country skiers, climbing three miles to the summit and carving telemark turns through the powder. Before long, however, rope tows began hauling skiers up the slopes.

Public knowledge of the sport was limited in those days. One 1940 visitor to the lodge was astonished to discover that the ski slope was, well, such a slope.

“It’s all downhill!” she said, amazed. “I thought you had to hit a flat spot before skis would stop.”

The mountain was not exactly a refuge from outraged nature. In March 1945, eight men and one woman were marooned at the Mount Spokane lodge for four days after a blizzard buried their cars to the roofs.

The woman, identified as a “slim blonde” named Miss Margie Stumbo, told reporters afterward that she “had a lot of fun and I didn’t care whether we got out in a hurry or not.” Her only regret, she said, was that she had only two pair of ski trousers with her.

By 1946, it wasn’t unusual for hundreds of skiers to be on Mount Spokane on a Saturday or Sunday. In 1947 one of the world’s first double chairlifts was installed.

From then on, Mount Spokane became increasingly identified with skiing, not to mention snowboarding and snowmobiling. Today, the mountain is the site of the Mount Spokane Ski and Snowboard Park and – in an echo of the mountain’s earlier forms of skiing – the site of a 25-kilometer cross-country ski trail complex. The mountain hosts the annual Langlauf Nordic ski races.

A park, a vista point, a winter and summer recreation haven – nearly all of Francis Cook’s dreams for the mountain have come true. He died too early to see them, but he left an exceptionally tall and imposing monument.