Grisham’s ‘Innocent’ brings to life true tale of injustice

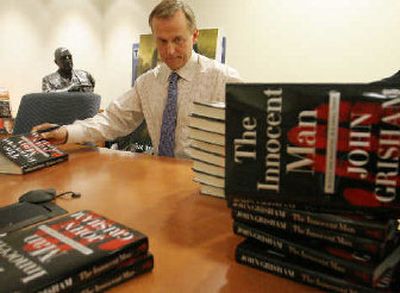

“The Innocent Man: Murder and Injustice in a Small Town”

by John Grisham (Doubleday, 368 pages, $28.95)

John Grisham’s journey into new territory began with an obituary.

It was the story of Ron Williamson, a one-time draft choice of the Oakland A’s who washed out of baseball and became a drunk, was convicted of a rape-murder and sent to Death Row, then was exonerated by DNA.

The December 2004 obituary for the 51-year-old Williamson set the best-selling novelist down the unfamiliar path to writing his first work of nonfiction, “The Innocent Man: Murder and Injustice in a Small Town.”

Instead of drawing characters and plot from his imagination, as he has done in more than a dozen novels, Grisham traveled to Williamson’s Oklahoma hometown and other locations, studying court records and conducting interviews to bring the story to life.

“Not in my most creative moment could I conjure up a story as rich and as layered as Ron’s,” Grisham writes in his author’s note.

The result, though, is a rather straightforward account of the case against Williamson and his co-defendant, Dennis Fritz. Grisham dissects the police investigation and prosecution with a surgeon’s precision, clearly benefiting from telling a story that is well-documented and oft-told. But he writes the story with such restraint that, at times, he fails to arouse sufficient anger at the miscarriage Williamson and Fritz suffered.

The crime at the center of “The Innocent Man” is the December 1982 rape and murder of Debbie Carter, a 21-year-old waitress at a beer hall and honky-tonk called the Coachlight in the small town of Ada, Okla.

Carter was strangled with an electrical cord. A washcloth was stuffed deep into her mouth. On a table and a wall in her apartment where her body was found, as well as on Carter’s back, her killer scrawled messages in ketchup.

Grisham signals in the first pages that the real murderer is Glen Gore, another local who danced with and later argued with Carter the night before she was found dead.

But, as in so many wrongful-conviction tales, the police and prosecutors went down the wrong road. In Grisham’s telling, they were negligent and corrupt, hiding evidence and ignoring signs that pointed away from Willamson and Fritz and to Gore.

While Grisham charts the police investigation, he also chronicles Williamson’s life and eventual mental slide. The son of churchgoing parents, he was a local baseball standout, and his only hope to leave Ada was through the sport – just like his hero, Mickey Mantle, another Oklahoma kid.

But it all quickly turned sour. In the A’s clubhouse one day, superstar Reggie Jackson humiliated the young hopeful. Williamson then blew out his arm, dashing his hopes of making a life in the major leagues. When he turned more and more to drinking, his wife divorced him.

The failures were crushing. Williamson’s drinking got worse. He began to display signs of the mental illness that would dog him the rest of his life.

Williamson was accused twice of rape, and though acquitted each time, the luster of his youth was clearly gone. He got and lost a series of menial jobs. He began to spend long hours sleeping on his mother’s couch.

As Carter’s murder went unsolved, the police grew frustrated. They nursed a hunch that Williamson and Fritz were involved but found no evidence to prove it; indeed, all the physical evidence pointed away from the pair.

Williamson insisted he had nothing to do with the killing, but police squeezed him until he finally agreed to a “dream confession” using details provided by detectives to incriminate himself.

The confession alone was not enough, however. So the prosecutor ordered Carter’s body exhumed, and a top state fingerprint examiner took prints again and again, comparing them to Williamson’s. Finally, he concluded they matched.

His mental illness raging, Williamson repeatedly disrupted his trial, yelling that he was innocent and should be released. When he was sent to Death Row, he screamed through the night for anyone who would listen that he was wrongly convicted; at one point, he came within five days of execution.

That he went free is almost a fluke. A federal judge took an interest in the case and ordered a new trial. Then attorneys for Williamson and Fritz obtained DNA testing that proved conclusively that neither man was involved in Carter’s murder – and eventually led to Gore’s arrest and conviction.

Although at times he allows an unnecessary sarcasm to emerge in his writing, Grisham draws sober lessons about the flaws in the criminal-justice system. With his large and devoted following, he is sure to expose a massive audience to a subject many readers might otherwise avoid.