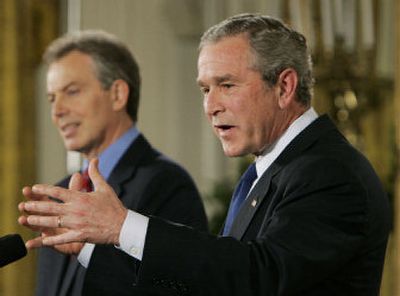

Bush, Blair admit to mistakes in Iraq

WASHINGTON – President Bush and British Prime Minister Tony Blair made unusual admissions of error regarding Iraq on Thursday, but they also said the seating of a democratically elected government after three years of fighting should inspire the world to ensure the success of a free Iraq.

Despite the assertion by the new Iraqi prime minister that Iraq may be able to manage its own security by the end of 2007, neither Bush nor Blair gave any indication of a time frame for the drawdown of military forces. Bush called reports that the Pentagon hopes to scale back the American deployment from 135,000 troops to about 100,000 by year’s end “speculation.”

“We want to make sure … we complete the mission,” Bush said in a nearly hour-long televised White House news conference. “I want our troops out. Don’t get me wrong. … I fully understand the pressures being placed on our military and their families. But I also understand that it is vital that we … do the job.”

In a side-by-side appearance in the East Room, a session devoted largely to somber discussion of the war but also marked by banter between two leaders who communicate frequently, Bush and Blair offered candid admissions about missteps made.

For Bush in particular, an admission of regrettable “tough talk” since the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, was an uncharacteristically personal comment.

“Saying, ‘Bring it on’ – kind of tough talk, you know – that sent the wrong signal to people,” Bush said somberly, in response to a British reporter’s question. “I learned some lessons about expressing myself maybe in a little more sophisticated manner. You know, ‘Wanted dead or alive,’ that kind of talk. I think in certain parts of the world it was misinterpreted. And so I learned – I learned from that.”

Bush was referring to comments he’d made that came to symbolize what some saw as swaggering, belligerent style: Shortly after the attacks he said he wanted Osama bin Laden “dead or alive,” and on another occasion he said of the Iraqi insurgents, “Bring it on.”

Bush also referred to the American military’s abuse of inmates at the Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq: “We’ve been paying for that for a long period of time.”

Blair said that in retrospect, he may have underestimated how long it would take to establish a democracy in Iraq. “I’m afraid, in the end we’re always going to have to be prepared for the fall of Saddam not to be the rise of democratic Iraq, that it was going to be a more difficult process,” Blair said.

Acknowledging that the decision to remove Saddam Hussein was “divisive … and indeed controversial” in the international community, Blair maintained that now “we should be determined to help them defeat this terrorism and violence.”

Since the U.S.-led invasion of Iraq in March 2003, Blair has been Bush’s staunchest ally, first in the overthrow of former Iraqi leader Saddam Hussein and then through more than three years of costly combat following the ouster.

Blair came to Washington for talks with Bush after meeting with the new Iraqi prime minister Nouri al-Maliki earlier this week.

Al-Maliki has said that Iraqi security forces should be able to manage the nation’s security by the end of 2007, raising anew questions of when U.S. and coalition forces might scale back.

But Bush dismissed reports of the Pentagon eyeing a drawdown to 100,000 this year as “some speculation in the press that … they haven’t talked to me about.”

Bush and Blair have seen their political fortunes slide as opposition to the war has increased. Bush held the approval of just 33 percent of the American public in the latest Gallup Poll, an early May survey. Blair, early in a third and increasingly difficult term as prime minister, claimed the approval of just 27 percent of British voters in a recent Daily Telegraph survey – the lowest rating for any Labor Party leader in modern times.