‘Religious left’ experiencing a revival

WASHINGTON – The religious left is back.

Long overshadowed by the Christian right, religious liberals across a wide swath of denominations are engaged today in their most intensive bout of political organizing and alliance-building since the civil rights and anti-Vietnam War movements of the 1960s, according to scholars, politicians and clergy members.

In large part, the revival of the religious left is a reaction against conservatives’ success in the 2004 elections in equating moral values with opposition to abortion and same-sex marriage.

Religious liberals say their faith compels them to emphasize such issues as poverty, affordable health care and global warming. Disillusionment with the war in Iraq and opposition to Bush administration policies on secret prisons and torture have also fueled the movement.

“The wind is changing. Folks – not just leaders – are fed up with what is being portrayed as Christian values,” said the Rev. Tim Ahrens, senior minister of First Congregational Church of Columbus, Ohio, and a founder of We Believe Ohio, a statewide clergy group established to ensure that the religious right is “not the only one holding a megaphone” in the public square.

“As religious people, we’re offended by the idea that if you’re not with the religious right, you’re not moral, you’re not religious,” said Linda Gustitus, who attends the River Road Unitarian Church in Bethesda, Md., and is a founder of the new Washington Region Religious Campaign Against Torture.

“I mean, there’s a whole universe out there (with views) different from the religious right. … People closer to the middle of the political spectrum who are religious want their voices heard.”

Recently, there has been an increase in books and Web sites by religious liberals, national and regional conferences, church-based discussion groups, and new faith-oriented political organizations.

“Organizationally speaking, strategically speaking, the religious left is now in the strongest position it’s been in since the Vietnam era,” said Clemson University political scientist Laura Olson.

What is not clear, according to sociologists and pollsters, is whether the religious left is growing in size as well as activism. Its political impact, including its ability to influence voters and move a legislative agenda, has also yet to be determined.

“I do think the religious left has become more visible and assertive and is attempting to get more organized,” said Allen Hertzke, a University of Oklahoma political science professor who follows religious movements. “But how big is it? The jury is still out on that.

“My gut tells me that all this foment (on the religious left) is bound to create more involvement in politics,” he said. “I don’t know whether there’s going to be more of them numerically, but you don’t need greater numbers to have a political impact; all you need is to be more active. You already see that in Ohio and some other states, where Christian conservatives no longer have a monopoly on faith in politics.”

Conservative Christian activist Gary Bauer said the religious left “is getting more media attention” but “it’s not clear” that it is getting more organized.

“My reaction is ‘Come on in, the water’s fine’ … but I think that when you look at frequent church attenders in America, they tend to be pro-life and support marriage as one man and one woman, and so I think the religious left is going to have a hard time making any significant progress” with those voters, he said.

The quickening pulse of the religious left is evident in myriad ways:

•More than a dozen books have been published in the past year decrying the religious right’s influence in politics. Three have been particularly influential in galvanizing activists: Michael Lerner’s “The Left Hand of God: Taking Back Our Country From the Religious Right,” Jim Wallis’ “God’s Politics: Why the Right Gets It Wrong and the Left Doesn’t Get It,” and Jimmy Carter’s “Our Endangered Values: America’s Moral Crisis.”

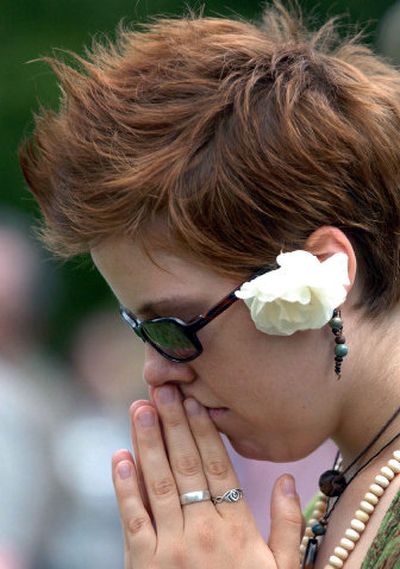

•The recently formed Network of Spiritual Progressives held a four-day conference that ended Saturday at All Souls Church in Northwest Washington. A thousand participants from 39 states discussed a new “Spiritual Covenant for America” and spent Thursday visiting their members of Congress. Lerner, the California-based rabbi who founded the network, said the conference was partly aimed at countering an aversion to religion among secular liberals and “the liberal culture” of the Democratic Party.

“I can guarantee you that every Democrat running for office in 2006 and 2008 will be quoting the Bible and talking about their most recent experience in church,” he said.

•The Democratic Faith Working Group, made up of 30 members of the House and scores of aides, has begun meeting monthly on Capitol Hill to discuss faith and politics, opening each session with a prayer. Its purpose is to “work with our fellow Democrats and get them comfortable with faith issues,” said its chairman, Rep. James Clyburn, D-S.C., a preacher’s son who was raised in the fundamentalist Church of God.

•Organizations and Web sites that meld religion and liberal politics have mushroomed since the 2004 elections, said Clinton White House chief of staff John Podesta. The think tank he heads, the Center for American Progress, has helped form alliances between some of these new groups – such as Faith in Public Life, the Catholic Alliance for the Common Good and FaithfulAmerica.org – and long-standing organizations, such as the National Council of Churches.

For most of the 20th century – from the Progressive era through the civil rights movement – religious involvement in American politics was dominated by the left.

That changed in the 1970s, after the Supreme Court’s Roe v. Wade decision on abortion rights, the formation of the Rev. Jerry Falwell’s Moral Majority, and, on the left, “the rise of a secular, liberal, urban elite that was not particularly comfortable with religion,” said Will Marshall III, president of the Progressive Policy Institute, a Washington think tank.

Some groups on the religious left are clearly seeking to help the Democratic Party. But the relationship is delicate on both sides.

“If I were the Democrats, the last thing I would do is really try to mobilize these folks as a political force … because I think some of this is a real unhappiness with the whole business of politicizing religion,” said Mark Silk, director of the Leonard E. Greenberg Center for the Study of Religion in Public Life at Trinity College in Hartford, Conn.

The Rev. Joseph W. Daniels Jr., senior pastor of Emory United Methodist Church in Northwest Washington, said a key question for him is whether the religious left will become “the polar opposite to … the religious right” or be “a voice in the middle.”

“What this country needs is strong spiritual leadership that is willing to build bridges. We don’t need leaders who are lightning bolts for division and dissension,” he said.

Nonetheless, some observers doubt that the revitalization of the religious left will lessen the divisions over religion in politics.

“I do think,” said Hertzke, “that, if in fact this progressive initiative takes off, we will see an even more polarized electoral environment than we did in 2004.”