Investing in good will

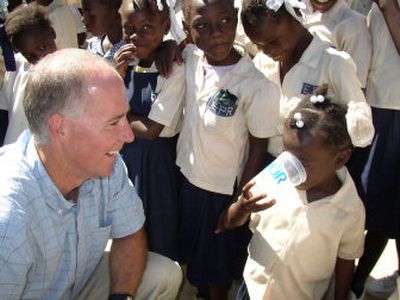

CINCINNATI — Greg Allgood’s job at Procter & Gamble Co. has taken him to remote, disease-plagued villages in Kenya, into some of the Western Hemisphere’s poorest slums in Haiti, across rebel-ridden territory in Uganda and to tsunami-devastated Sri Lanka and earthquake-ravaged Pakistan.

While most people who work for the Cincinnati-based company sell consumer products such as Crest toothpaste and Pampers diapers, Allgood is the director of the Children’s Safe-Drinking Water Project. The charitable program aims to curb the nearly 2 million child deaths attributed annually to polluted water with a water-cleansing product called Pur that the company donates or sells at cost.

Like other major U.S. companies with international interests, P&G sees long-range business benefits in charitable projects in developing countries, what some call “strategic philanthropy.”

“We’re not a for-loss company,” Allgood said. But there is strong backing among P&G’s leaders for the charitable project. Companies that work to improve health and education overseas also can improve their images in foreign countries and among consumers at home. They can reap benefits to employee morale and recruiting. And they can lay the groundwork in future markets.

“We’re going into some of these countries where P&G has no presence,” Allgood said. “And maybe it’s 50 years from now when we have business in Haiti, but someday, we’ll want to. What better way to learn the distribution infrastructures and government relationships than coming in with a product that’s saving lives?”

U.S. corporate donations overseas have been increasing in recent years, highlighted by the more than $566 million in contributions to tsunami relief, according to the Business Civic Leadership Center for the U.S. Chamber of Commerce. The center hasn’t compiled statistics on ongoing charitable projects but says they are on the increase, too.

A sampling: Starbucks Corp. provides support to coffee- and tea-growing communities around the world and works to improve education in rural China and Guatemala. Johnson & Johnson Co. programs include eye health in Asia, diabetes treatment in Mexico and fighting pediatric AIDS in China, Russia and other countries. General Electric Co. programs include support for rural teacher training in China and education for slum children in India. In most cases, the corporations partner with nonprofit agencies.

“I think there are various ways you can engage in these kinds of activities; there are a lot of different models out there,” said Brenda Colatrella, senior director for Merck’s office of contributions. “You try to create the least amount of bureaucracy and get the most done with your partners.”

Merck, based in Whitehouse Station, N.J., has been working since the 1980s with partners including former President Jimmy Carter’s Atlanta-based Carter Center to donate drugs that combat river blindness in Africa. The company also provides vaccine training to African health professionals, among other programs.

“One of the upsides of globalization is companies looking at developing countries and ways they can help,” said Eric Fernald, research director for Boston-based KLD Research & Analytics Inc., which tracks corporate social performance.

American corporations often face skepticism and suspicions overseas about their motives. Being associated with charitable activities and forming local partnerships helps companies gain acceptance and build long-term relationships.

Besides being sensitive to the needs of the developing world, U.S. corporations must also be sensitive to their images following corporate scandals such as the collapse of Enron Corp., said Noel Tichy, a University of Michigan business professor.