Booyah! Investment guru touts with clout

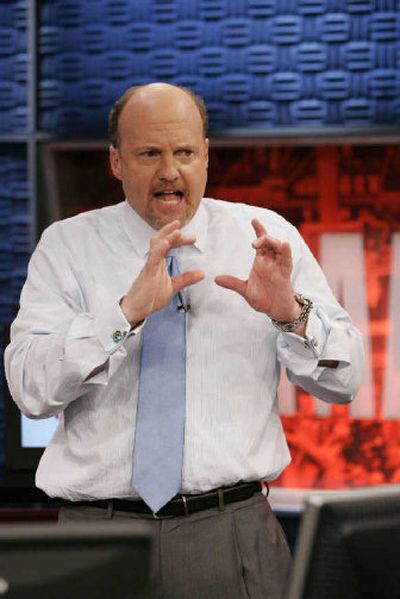

ENGLEWOOD CLIFFS, N.J. — Inside a darkened television studio, Jim Cramer, the hyperkinetic, “Booyah!”-braying host of CNBC’s hit cable television show “Mad Money,” munched on his salad lunch, talking contentedly about all his stock picks that turned to gold. Then his expression changed.

With a haunted look, Cramer recalled his worst stock market advice: the recommendation that followed a trip last year to visit a beleaguered company. “Symbol Technologies is probably the single biggest disappointment I’ve had since I started my show,” Cramer said about the Long Island, N.Y.-based bar-code scanner manufacturer whose stock plummeted after he was persuaded against his better judgment to give it a plug.

“I wish I had never heard of this,” said Cramer, 51, before recounting a story about the stock he should have shorted. “It (Symbol’s stock price) just blew up the other day.”

But Symbol is far from the only company getting Cramer’s laserlike, turn-up-the-volume attention these days. With a stock market meandering sideways since the 1990s high-tech bubble burst, Cramer’s unvarnished stock assessments are gobbled up every night by thousands of investors. Since his show debuted a year ago, his top picks have earned more than double the rate of both the Dow Jones and the Nasdaq averages, creating a Cramer effect in the market the day after he praises or pans a stock.

“Watching ‘Mad Money’ is like a visit to the loony bin,” observed Harry Domash, a fellow investment adviser in California. “But whatever you think of Cramer’s persona, he can help you make money in the market.”

Susan Krakower, CNBC’s vice president of strategic development, who dreamed up the program with Cramer, says ratings have more than doubled because the show appeals to both die-hard traders and an average audience following the market and their 401(k)s.

Krakower wanted Cramer to be “riveting, theatrical and provocative,” unlike other business shows that seem as exciting as reading stock tables. But she adds, “There’s a lot of math and education that goes into his work, and he’s sometimes funny, too. That’s why he’s a cult hit.”

Cramer is a one-man cottage industry of financial advice. Besides hosting “Mad Money,” he writes for TheStreet.com Web site he launched and partly owns, does a column for New York Magazine and hosts a daily radio show newly signed by the CBS radio network.

Cramer, a Harvard Law grad and former hedge fund manager reportedly worth as much as $100 million, says he’s careful not to step over the line legally. His own stock portfolio is kept in a trust with all its proceeds pledged to charity.

Cramer starts each workday by perusing financial news and business charts before meeting with his staff to select the stocks he’ll talk about on his show. His own research will range from examining SEC disclosure statements to chatting about trends with old hedge fund friends.

Seated at his TV desk, Cramer began to worry that he wasn’t yet up to speed on that day’s market trends. “I still don’t have the feel and texture of today,” he said, nervously typing on the laptops flashing market results before his eyes, trying to catch up.

While checking out stocks, he returned to the example of Symbol Technologies. As he tells the story, Cramer first commented critically about Symbol on his radio show in late 2004.

He soon got a complaint about unfairness from Bo Dietl, a former New York cop turned corporate investigator, who made the call at the behest of a pal working for Symbol. After talking with Dietl, Cramer agreed to meet with Symbol’s then-newly installed chief executive, Bill Nuti.

The three went to dinner at Manhattan’s Sparks Steakhouse, Cramer says, and he agreed to visit Symbol’s headquarters, where Nuti talked of all of the company’s new Homeland Security work and the high-tech devices it was developing.

Cramer said he was “dazzled” by Nuti’s presentation, so he recommended Symbol stock, resulting in a rise in its share price.

But by June 2005, Symbol’s stock had plummeted from a high of $16 to about $10 a share, and Cramer was kicking himself for recommending it. Nuti soon left Symbol and now heads a different firm in Ohio.

Nuti could not be reached for comment, but Dietl confirmed Cramer’s account. Usually, Cramer tells investors to do their homework: Check the financial performance of companies and do a careful analysis of their finances before plunking down money on stocks. He estimated only about a third of investors do adequate research with their stock moves.

But in Symbol’s case, Cramer laughs that perhaps he did too much homework, allowing himself to tout this company despite his underlying doubts.

“I contravened one of my own rules,” admits Wall Street’s reigning financial guru.