Photographs capture passion and pain of historic civil rights march King & I

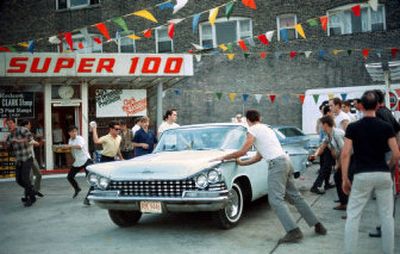

The mob threw rocks, lobbed cherry bombs, hurled insults and racial slurs. “I wouldn’t do that if I were you,” Bernard Kleina growled when they spat on him for marching in Chicago on July 31, 1966.

Before he could unleash his outrage, an older African American man walking in front of him turned around. “Remember why you’re here, brother,” he said.

His words reminded Kleina to follow the example of those who didn’t lift a finger against the abuse of the crowds. They marched in silence – in the name of peace, justice and civil rights.

Kleina, a teacher and Roman Catholic priest at the time, was among thousands who took part in the 1966 Chicago Freedom Movement, the country’s first large-scale fair housing campaign.

Despite the hatred he endured during the July 31 march, Kleina joined the activists for another gathering five days later. But instead of walking quietly, he brought a camera.

Led by the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., that march into Chicago’s southwest side became one of the movement’s defining moments. And Kleina, who was relatively inexperienced as a photographer at the time, was able to capture the historic event on film – from the determination on King’s face and the tension that permeated the crowds to the rage displayed by detractors who called them names and screamed “White power!”

Beginning Friday, these rarely seen photographs of that march and other images from the Chicago Freedom Movement will be shown in Spokane’s Community Building for national Fair Housing Month.

Kleina, the executive director of HOPE Fair Housing Center in Wheaton, Ill., will be in Spokane that night to share his memories of the civil rights movement. He’ll also talk about efforts to fight housing discrimination, a problem that persists today.

“These photographs remind us of what Fair Housing Month really stands for,” said Marley Eichstaedt, executive director of Northwest Fair Housing Alliance, the exhibit’s sponsor.

“Too often, people think of fair housing obligations as just another set of procedural landlord-tenant rules to be followed, like those for returning security deposits or giving termination notices. Fair housing laws actually ensure our civil right to live where we want to.”

The exhibit in Spokane is only the fourth public showing of these images from Chicago – Kleina’s hometown and the first northern city in the United States where King and other activists focused on issues of poverty and housing segregation.

“There was a lot of criticism of the marchers, the purpose and the marches themselves, so I wanted to show the critics that they were mistaken,” Kleina said during a phone interview earlier this week.

He was 30 at the time and an assistant pastor for a white, relatively affluent parish in the Diocese of Joliet, Ill. Although he had taken pictures and participated in other marches, including several in Selma, Ala., the previous year, the Aug. 5 march with King was the first time that he felt safe enough to pull out his camera and document history.

A white man who grew up on Chicago’s west side, Kleina decided to get involved in the civil rights movement after witnessing the way marchers were treated by police during the historic march from Selma to Montgomery.

“People were being clubbed to the ground, but the marchers were so disciplined,” he recalled. “They didn’t retaliate. They didn’t fight back. That was part of their strength.”

Kleina was shocked at first by people’s reactions when he took part in the demonstrations. He saw hatred in their eyes, a fury that he couldn’t fathom.

Just minutes after the Aug. 5 march began, King was hit with a rock, causing him to fall to his knees, Kleina recalled. He was able to get up and continue marching through the hostile white neighborhood along with hundreds of others.

According to a historic account of the movement compiled by the Poverty and Race Research Action Council, the 500-plus marchers later encountered 4,000 angry whites waiting for them at nearby Marquette Park. About 30 marchers were injured, but more may have been hurt had it not been for the presence of police officers.

After the procession, King said that he had “never seen as much hatred and hostility on the part of so many people.”

Although Kleina’s exhibit includes many images of King and his wife, Coretta Scott King, the photographer never had the privilege of sitting down and talking to them. The marches and demonstrations were often stressful, he said, so there wasn’t a good time to approach them.

“Witnessing him changed my whole life,” said Kleina. “I was always drawn to King because of his practice and spirit of nonviolence.”

Two years after the Chicago Freedom Movement, he left the priesthood and devoted his life to fair housing.

“I thought I could do a better job in civil rights outside the priesthood,” said Kleina, 70, the HOPE executive director for the past 36 years.

“I would think civil rights is something that all churches should be involved in, but they’re not. It wasn’t happening then and it’s not happening today. Many (religious leaders) are concerned about buildings and collection baskets and not as concerned about the poor as they ought to be.”

Looking back at his experience during the civil rights movement, Kleina said he was actually more hopeful then than he is today.

“The struggle continues,” he said, noting the huge volume of calls HOPE Fair Housing receives each year from people who have experienced discrimination.

In the Spokane area alone, 165 verified complaints of housing discrimination were reported to Northwest Fair Housing Alliance last year.

“Even though considerable change has taken place,” Kleina said, “we still have a long way to go.”