Bank records access defended

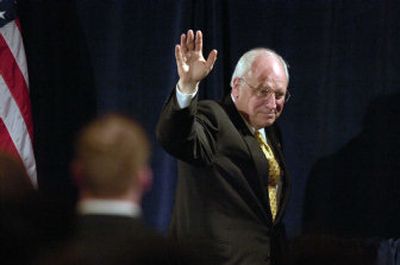

WASHINGTON – A secret program that allowed U.S. officials to examine hundreds of thousands of private banking records from around the world in search of terrorist ties has been “absolutely essential” to protecting the country from further attacks, Vice President Dick Cheney said Friday.

Outgoing Treasury Secretary John Snow said that the program, in effect since shortly after the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks, was the thing “I’m proudest of” during his tenure and insisted that strong safeguards protected the privacy of individual Americans. “It’s really government at its best,” Snow said. “It’s responsible government. It’s effective government.”

The comments by Cheney, Snow and other senior Bush administration officials were made the day after news organizations exposed the surveillance effort, in which the Treasury Department has subpoenaed data from an international banking cooperative that serves as a messaging service for overseas monetary transfers.

The revelations – which Cheney and other officials said undermined an important counterterrorism tool – prompted renewed criticism from Democrats and civil liberties groups that the administration was operating outside legal and congressional controls.

“It would be very disturbing to me to find out that this program represents yet another unilateral action and further abuse of executive authority without proper safeguards and oversight,” said Rep. Barney Frank of Massachusetts, the senior Democrat on the Financial Services Committee. Others described the program as an invasion of privacy and called for hearings on possible violations of domestic and international law.

But far from giving ground, the administration mounted a muscular defense of the program, dispatching its principal Treasury Department supervisor to explain how it worked. The tactic was in sharp contrast to the administration’s refusal to provide details about other secret programs that had been revealed earlier by news organizations, including the National Security Agency’s warrantless wiretaps of overseas calls made by U.S. citizens and residents.

At the White House, spokesman Tony Snow acknowledged that the program relied on an expansive interpretation of Treasury’s powers that was unusual. “Well, so was September 11,” he said.

The program falls well within the president’s executive authority, Snow asserted, and President Bush did not need to seek congressional authorization, although legislative oversight committees “know all about it.”

There was some disagreement Friday, however, over who had been briefed on the program and when. The White House referred reporters to Sen. Christopher Bond, R-Mo., who said he had been informed about the secret effort four years ago, when he was named chairman of an appropriations subcommittee overseeing the Treasury Department. “I think it is a tremendous tool,” Bond said.

Although the chairmen and senior Democrats on the two intelligence committees apparently were also briefed when the program began, there have been changes in the intelligence committee leadership since 2001. The full committees – and the current chairmen and senior Democrats in some cases – learned of the program in May, when CIA and Treasury Department officials offered new briefings after learning that the New York Times was preparing an article on it, a Treasury official said.

Some members on the several committees that oversee the Treasury Department appeared to have been left in the dark.

U.S. counterterrorism officials obtained the financial records from an international banking cooperative called the Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunications. Known as SWIFT, it is owned and controlled by nearly 8,000 commercial banks in more than 20 countries that use its services.

While headquartered in Brussels, much of its operations are based in the United States, where knowledge of the government’s secret access to its data was not widespread. Of officials at three large U.S. banks who agreed to speak about the program, only one said his institution had knowledge of it before Friday.

“People around here are fine with this,” said the official at a major New York bank, who requested anonymity. “It was done right.”