Love story, rare stamp reunited

WASHINGTON — In the stamp collecting world, the tiny square on the outside of an envelope is often all that matters. It is the commodity that is coveted and traded and sold. But for some, there is also the draw of the story behind the stamp — where it came from, the time it represents, the printing mistake that alters it just a bit from others like it.

And so it was with the Alexandria Blue Boy — a stamp that carried a love letter in 1847 between a couple that for many reasons should not have been. They were second cousins. He was Presbyterian; she was Episcopalian. Relatives were watching.

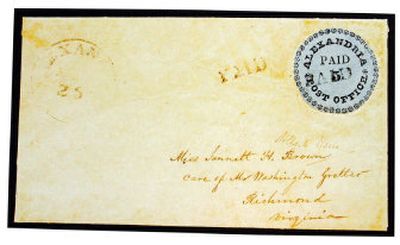

One of the rarest stamps in the world, the Blue Boy sold for $1 million in 1981 and is estimated to be worth many times that now. Still, many wondered why this stamp — an Alexandria postmaster provisional printed on blue paper before U.S. government stamps were commonplace — survived when all others like it were lost or destroyed. If the envelope had been saved for sentimental reasons, did the letter also exist? If so, what did it say?

“Did these two people ever get married?” said Gordon Morison, executive director of the Washington 2006 World Philatelic Exhibition, a stamp show on a scale seen in the United States only once every 10 years.

Last fall, as Morison and others prepared for the exhibition, he wondered aloud about the Alexandria Blue Boy to May Day Taylor, a fellow philatelist who was volunteering at the show.

“We wondered where the letter was or if it even existed anymore,” he said. “I did not ever expect we’d find the letter. Frankly, that stuff is not saved.”

But on that September day Taylor began her search — one that sometimes consumed 40 hours in a week and regularly took her from her D.C. home to suburban Alexandria, Va. She went through the Alexandria phone book, then sat for hours in libraries researching dates, genealogies and the history of the postal service.

From the envelope, she had a name: Miss Jannett H. Brown. And she had a general address: Richmond, Va. What she re-created from there was a time and a place long gone.

The Alexandria post office that issued the stamp is now an antique store and the days of horse-drawn carriages are distant, but Taylor said she could stand at one end of Prince Street, on the cobblestones that remain, and see the story unfold through her research.

She found that Jannett Hooff Brown lived at 517 Prince St., a few blocks from her second cousin James Wallace Hooff, at 1016 Prince St. They were 23 and 24 years old. In between them lived Daniel Bryan, who was both the postmaster and a poet, although his verses were considered long-winded and grandiose. He is believed to have created the Blue Boy, which consists of a circle of 40 rosettes around the words “Alexandria Post Office.” And contrary to previous reports, the Blue Boy stamp was not used in 1846, but rather in 1847, even after the U.S. government had issued its own.

“It’s that putting together of all the pieces that makes for a beautiful picture, a snapshot of what it was like in a different day and time,” Taylor said.

The break in Taylor’s research came when she discovered that Hooff and Brown had indeed married and that their descendants lived in Alexandria. She visited one day around Christmastime, hoping to get as many relatives together as possible to discuss the task at hand: finding the letter.

Waiting for her was an old scrapbook pulled from a basement.

On the first page was a picture of the Blue Boy on the envelope. Then, she saw grainy photographs of Brown and Hooff, black-and-white prints turned brown over time. And finally, on the next page, folded in a yellowed envelope with a note identifying it, was the letter.

In the careful, elaborate penmanship of another era, the letter began with the place and time: Alexandria, Va. Nov. 24th 1847. It was sent to Richmond, where Brown was visiting relatives. Mostly it tells of family happenings.

There is no marriage proposal.

“Reading the letter evokes different emotions for different people,” Taylor said. “There are some people who read the letter and say it’s a wonder they ever had children. … If you are expecting a marriage proposal and something gushy and hearts and flowers, it’s probably going to be a disappointment.”

Instead, there is restraint in Hooff’s words, an air of distance that only occasionally allows his emotions to peek through.

“The reasons you give for not writing often, are good, for your cousin Wash. will be certain to say something, if you give him all your letters, to put in the office,” Hooff writes. “But whenever you think you can write me a line without exciting the attention of your coz. Wash, do so, for it gives me a great deal of pleasure to receive a letter from you, even if it is only a short one.”

And: “Bye the bye, I believe Aunt Julia has an idea of my writing you; for two or three days after my first letter to you, she wrote Mother,” Hooff writes, adding that his mother and sisters later referred to Aunt Julia as a “prophet” in front of him. “And Mother laughingly remarked ‘That if there was any love going on Aunt Julia was sure to find it out,’ and while making that remark, I think, looked at me, but I continued reading, as if what she said did not apply to me in the least.” It is signed: “Yours with the greatest affection, W”

Six years later — after Aunt Julia left Richmond for Albany, N.Y. — the two were married. Eventually they had three children.

Their oldest daughter, Mary Fawcett, who found the envelope in a sewing box, sold it in 1907 to a stamp collector. Now, almost a century later, the letter and stamp — on loan from an anonymous owner who lives in Switzerland — were reunited at this week’s Philatelic Exhibition at the D.C. Convention Center.

Morison said that even with more than $200 million worth of philatelic items on display, the Blue Boy story will be the star.

“Many wanted to know how the movie ended,” he said.

It ended as it began, with a letter that should have been destroyed.

“Burn as Usual,” Hooff had written on the bottom.