Candidate’s headquarters has a dark history

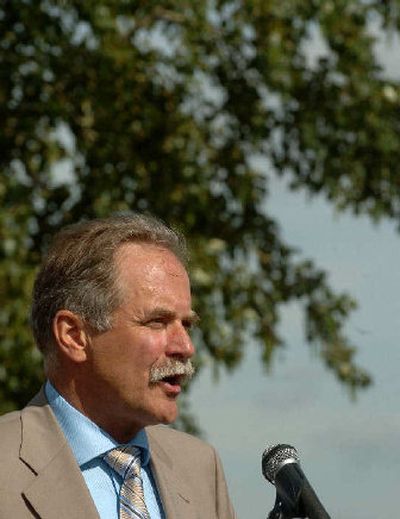

Congressional candidate Peter Goldmark doesn’t believe in ghosts, or bad karma attaching itself to buildings.

That may be a good thing, in light of an odd coincidence involving the building where Goldmark and other Democratic candidates have their Spokane campaign headquarters.

The campaigns occupy the brick-fronted building at 151 S. Washington that once housed the offices of a man who tried to ruin Goldmark’s father, John, and effectively ended the elder Goldmark’s political career some 44 years ago.

That man was Al Canwell, a former state representative from north Spokane who once held sway in the Legislature the way Joe McCarthy bullied the U.S. Senate. During his single two-year term, Canwell’s Joint Legislative Committee on Un-American Activities hunted the “Red Menace” in Washington state, from the state Pension Board to theater groups in Seattle to the University of Washington.

Peter Goldmark said in a recent interview he never met Canwell, although he knows generally about his legislative career.

But it was Canwell’s later activities that affected Goldmark’s family.

Canwell lost his bid for election to the state Senate in 1948 and never won another election. But for decades he gathered “intelligence data” on people he suspected of being Communists. His newspaper, the Vigilante, and a newsletter he called the American Intelligence Service were in the building at South Washington for many years, and his investigative files were stored in the floors above.

In 1962, he teamed with an old ally, former Spokesman-Review political writer Ashley Holden, to accuse three-term Rep. John Goldmark of having communist ties because he was a member of the American Civil Liberties Union and his wife, Sally, had been a member of the Communist Party in the mid-1930s and early-1940s. Some of the allegations were contained in the Vigilante and the American Intelligence Service newsletter. The allegations cost Goldmark the Democratic primary that fall.

John Goldmark sued Canwell and Holden for libel in 1963 and won, in one of the most famous libel trials in state history. The $40,000 jury verdict was overturned two months later when the U.S. Supreme Court ruled a public official had to prove actual malice to win a libel case, and that hadn’t been part of the jury’s instructions.

Goldmark said he wouldn’t ask to have the case retried, saying the jury’s decision itself had cleared his name. He never ran for office again, and eventually moved to Seattle.

Peter Goldmark said he doesn’t remember much about that 1962 campaign. “I was just a youngster when that was going on.”

He remembers testifying briefly at the trial. Other than that, there was no big impact on family life.

“That happened to my parents. They were very good about keeping that away from us,” said Peter Goldmark, now an Okanogan rancher running for the U.S. House seat held by Republican Cathy McMorris. “It didn’t seem important.”

Canwell went back to running what he called a civilian investigative service, gathering and storing his files on suspected communists and subversives, information he claimed he made available to the Federal Bureau of Investigation whenever it wanted. Much of that information he stored in the three-story building at 151 S. Washington, which held American Intelligence Service into the 1980s, as well as other Canwell operations.

One night in the summer of 1984, an arsonist set fire to the buildings. The top two floors, and the files that were in them, were incinerated. The first floor offices survived the fire, and apartments were eventually added when the second floor was rebuilt.

Mary Kienholz, who owns the building and worked with Canwell for many years, said recently that documents dating to 1914 were destroyed in the fire, some of them of great historic importance.

In a 1998 interview, Canwell hinted that not everything went up in flames, and that he still had many documents that would incriminate prominent Spokane residents. But by then Canwell was 91 and in failing health. He was remembered, not fondly, on the 50th anniversary of his legislative hunt for communists at the University of Washington. He responded that communists were still a menace and that he’d never libeled John Goldmark.

Canwell died in 2002.

John Goldmark died in 1979, and his elder son Charles was murdered along with his wife and two children on Christmas Eve 1985 by David Rice, an unemployed welder who mistakenly thought they were communists. That impression was based in part on the 1962 accounts that accused John and Sally Goldmark of being communists; Rice’s attorneys said he confused Charles Goldmark with his father. Rice was convicted and is serving a life sentence.

When the Goldmark campaign staff and other Democratic officials chose the building for a headquarters several months ago, none of them knew its connection to Canwell. Kienholz, the building’s owner, didn’t know initially the space was being leased to Goldmark, because the lease was arranged through an agent.

“It’s an odd coincidence,” Kienholz said. “They’ve been good tenants. I wouldn’t want anything to stir up any acrimony.”

Goldmark, who learned of the building’s history only last month, said he doesn’t know if he would have objected if he knew that before the lease was signed. But he has no plans to move. The offices are on a main thoroughfare, close to downtown and have plenty of space, he said

“It’s an interesting little connection, but that’s all it is,” he said. “It’s unusual, but it’s Spokane.”