Story behind Astoria

ASTORIA, Ore. – If you miss its history, you miss Astoria. If you miss its eccentricities – and its eccentrics – you miss Astoria.

If you walk its riverfront and streets and climb its hills, hood up, bent over against a sideways rain, sopping wet, longing for some seafood and a beer and a place to drain the water out of your shoes – then finding it all and happily laughing at your perseverance – you will miss Astoria when you leave.

This city of 10,000, near the northwest tip of Oregon and just a few miles inside the notorious mouth of the Columbia River (called the “Graveyard of the Pacific” for the huge number of shipwrecks and deaths it’s spawned), can snare a visitor just as easily as its fishermen gaffed salmon as big as your leg – or bigger – decades ago.

But it needs to be given the opportunity. And you need to listen. For beneath its obvious tourist offerings, Astoria is bursting with desire to speak of its nearly 200-year-old history.

Steve Forrester, editor and publisher of The Daily Astorian newspaper, calls the city “one big attic.” Indeed, with several museums, ranging from the spectacular Columbia River Maritime Museum on the river to the jam-packed Clatsop County Heritage Museum up the hill, there is plenty of opportunity for Astoria history immersion therapy.

And just wait, Forrester says, “until there’s an estate sale. The stuff that comes out of some of those homes you wouldn’t believe.”

Astoria has been “rediscovered” of late by scribes spinning tales of its trappings for readers of everything from The New York Times to Sunset magazine.

They write of its restaurants, its new and newly refurbished accommodations – especially the accommodations.

Hotels like the 5-month-old Cannery Pier Hotel, built to resemble the fish cannery it replaced on a pier over the Columbia. And the refurbished, 80-year-old Hotel Elliott, right downtown, with a 360-degree view of the area from its rooftop garden. Hotels that have lured visitors from all over the world.

They write about Astoria’s Victorian homes, arguably the biggest collection in Oregon, and the shops that line Commercial Street and nearly all of the downtown side streets, where you’ll be hard-pressed to find a vacant storefront.

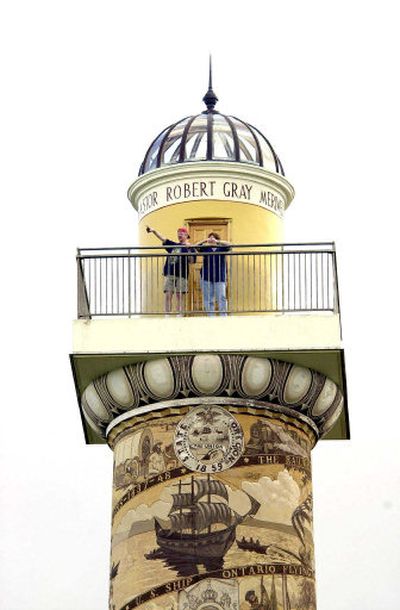

They sing of its three-mile waterfront trolley, which for an extra buck will stop and pick you up at just about any unmarked stop and can be so jammed at times that it takes about 40 minutes to get across town, some say (it’s usually a 45-minute round trip, give or take); and the view from atop the 700-plus-feet-above sea level Astoria Column, painted with scenes of local history and commanding a view on a clear day that will leave no jaw undropped.

And they are right. All of them. For these trappings, and more, are part of what has brought a resurgent flow of visitors to this river town.

But they aren’t the only ones on the comeback trail. There’s been a steady flow in the past few years of native Astorians “coming home.” And they’ve had an impact.

“What holds small towns back is the lack of ability to network upward and outward,” says Forrester. “The effect of these people is that they’ve been out in the wider world and they have contacts and they bring that expertise back with them.”

Robert “Jake” Jacob, born and raised on the river, is one. The architect built his Cannery Pier Hotel literally over the Columbia, under the south rise of the Astoria-Megler Bridge, on the pilings of the old Union Fishermen’s Cooperative Packing Co. – itself a lesson in salmon and labor history (displayed in galleries lining a hallway in the hotel and in a book written by Jacob’s brother Greg called “Fins, Finns and Astorians” to mark the hotel’s opening).

The hotel purposefully resembles a part of the original structure for which it’s named, so much so that one guest could be forgiven for insisting that the hotel was a remodel of the cannery.

“It’s not,” Jacob laughs, but later points out that he’d had plenty of guidance from former cannery employees who watched the building go up and insisted that he not muck it up, right down to the color of the exterior paint.

Across town and upriver, Floyd Holcom is another home-again native. A few years ago, he bought a different pier, also with old cannery buildings (a cannery that at one time made Bumble Bee tuna famous). In the years since, he’s redone the top floor of one of the cannery buildings, which now houses, among other things, techies, attorneys and three guest suites. A nearly completed pub and a developing small boat museum are taking up more space in what is now called Pier 39.

The newest arrival is Zetty McKay, who just opened her coffee shop, Coffee Girl, on the pier. She’s another Astoria native, a graduate of the University of Oregon, a former TV anchor who came home to be near her family and the coast. Now she makes soup and tests baked goods on her customers in the morning while she ramps up the business and has an afternoon show on a local radio station.

On shore, there’s a planned trolley stop and initial construction activity for a $15 million condominium project.

Like Jacob, Holcom’s description of his project and his future plans are shot through with Astoria history as the world’s one-time, premier fish-packing hub.

Holcom stands, with no small amount of awe, at a whitewashed wall inside the old cannery. There are scrawled the names, dates and jobs of many of the crowd of people who showed up for a Bumble Bee employees reunion that he sponsored last summer.

“Look at these names,” he says, and begins to read aloud and lecture on who did what.

He’s still hoping that more of Astoria’s long-time Bumble Bees will sign the wall. He plans a protective covering so the names will remain – for a long time.

Downtown is the Columbia River Maritime Museum, a spectacular, nearly over-the-top collection of the area’s seafaring history, from Astoria’s cannery days to its watch over the ships and fishing craft that pass it daily on the Columbia. In fact, the channel connecting the Pacific to ports in Vancouver, Wash., and Portland passes close enough to make the museum’s giant windows onto giant cargo ships one of the best exhibits imaginable.

But on one recent day, there were more than a few museum visitors who had braved winter storms to huddle around a display on bar pilots – the skilled mariners who board ships needing their assistance to cross the bar farther down river that separates the river from the ocean.

The channel is narrow there, the seas treacherous, often deadly. The clash of severe weather, river current and tide can build swells 20 feet high, sometimes higher.

The exhibit had taken on a somber reality that day. A raging storm had been blamed for the death of a Washington state pilot the night before who fell when trying to reboard his pilot boat after successfully steering a cargo ship into the ocean, the first such fatality in more than 30 years – a new and sad piece of Astoria history.

And that, locals say, is what you need to know about them when you visit – the history of those who’ve spent their entire lives in Astoria, who were born here and never left. Whose families were born here and never left. Who built the infrastructure that gave rise to a town loaded with architectural gems, museums, shops of every ilk, personalities of every description – and the chance to remake the city.

Forrester says he once asked a former bookstore owner why Astoria and its surrounds were such an eccentric place and attracted such an eccentric breed.

“She said there’s this theory in biology – or the life sciences – that the richest life forms are found at the very edge of ecosystems,” he says. “And here we are, at the edge.”

At first there were the natives – among them the Clatsop and Chinook Indians – who fished the Columbia and who would make salmon famous. Then came John Jacob Astor’s “Astorians,” who formed the first white settlement, hellbent on forming a trading empire.

Then there were immigrants from Finns to Italians, and the labors of imported Chinese. And corporations, and prostitutes, and bars and wild days and nights of rowdiness, unions and cooperatives and fighting and killings.

Then Astoria fell – thanks in great part to the depletion of the Columbia’s unbelievable salmon runs.

Nowadays, Mary Adams sits alone in the warmth of a tiny, gray visitor center at the top of Coxcomb Hill where the Astoria Column is bathed in fog and driving rain.

She’s another native. She knows why Astoria never completely fell off the map. And why it’s re-emerging.

“There was a survey and the tourists were asked to rank Astoria on a scale of one to 10. Someone gave it a 12!” she said. “Because there’s a city here. It’s real.”

How long will it last?

Many say as long as the cost of owning something here or even living here doesn’t skyrocket the way it has on the rest of the coast.

But Robert Jacob’s mother, Dorothy, had a better barometer.

“She used to say, ‘When noodles become pasta, when junk becomes antiques and when coffee becomes latte, get out,’ ” he says.

To be sure, there’s some pasta in Astoria – and antiques and even latte drive-throughs.

But there are too many of Forrester’s eccentrics, too many of Jacob’s old-timers and far too much of the smell of fish in the air to shut down the cannery town for good.

Insists Holcom: “I swear there are days … that I can still smell the tuna. I know I can.”